Are you wondering what is an XML sitemap, and how to add it to your WordPress website?

An XML sitemap helps search engines easily navigate through your website content. It gives them a list of all your content in a machine-readable format.

In this article, we will explain what is an XML sitemap, and how to easily create a sitemap in WordPress.

What is an XML Sitemap?

An XML sitemap is a file that lists all your website content in an XML format, so search engines like Google can easily discover and index your content.

Back in the early 2000s, government websites used to have a link on their main pages, titled “Sitemap”. This page usually contained a list of all the pages on that website.

While some websites still have HTML sitemaps today, the overall usage of sitemaps have evolved.

Today sitemaps are published in an XML format instead of HTML, and their target audience is search engines and not people.

Basically, an XML sitemap is a way for website owners to tell search engines about all the pages that exist on their website.

It also tells search engines which links on your website are more important than others, and how frequently you update your website.

While XML sitemaps will not boost your search engine rankings, they allow search engines to better crawl your website. This means they can find more content and start showing it in search results thus resulting in more search traffic, and improved SEO rankings.

Why You Need an XML Sitemap?

Sitemaps are extremely important from a search engine optimization (SEO) point of view.

Simply adding a sitemap does not affect search rankings. However, if there is a page on your site that is not indexed, then sitemap provides you a way to let search engines know about that page.

Sitemaps are extremely useful for when you first start a blog or create a new website because most new websites don’t have any backlinks. This makes it harder for search engines to discover all of their content.

This is why search engines like Google and Bing allow new website owners to submit a sitemap in their webmaster tools. This allows their search engine bots to easily discover and index your content (more on this later).

Sitemaps are equally as important for established popular websites as well. They allow you to highlight which part of your websites are more important, which parts are more frequently updated, etc, so search engines can visit and index your content accordingly.

That being said, let’s take a look at how to create XML sitemap in WordPress.

How to create a Sitemap in WordPress?

There are several ways to create an XML sitemap in WordPress. We will show you three popular methods to create an XML sitemap in WordPress, and you can choose one that works best for you.

Method 1. How to Create an XML Sitemap in WordPress without a Plugin

This method is very basic and limited in terms of features.

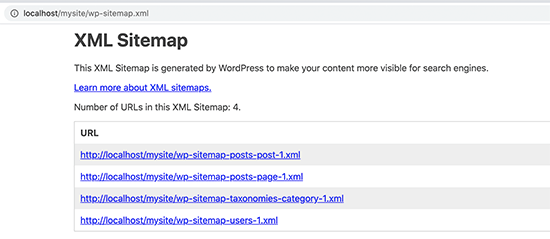

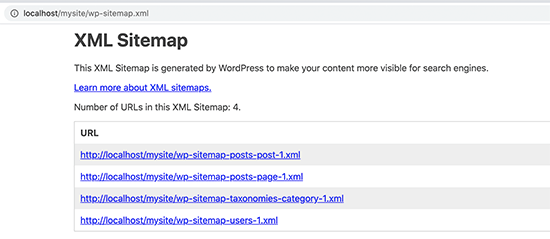

Until August 2020, WordPress didn’t have built-in sitemaps. However in WordPress 5.5, they released a basic XML sitemap feature.

This allows you to automatically create an XML sitemap in WordPress without using a plugin. You can simply add wp-sitemap.xml at the end of your domain name, and WordPress will show you the default XML sitemap.

This XML sitemap feature was added to WordPress to make sure that any new WordPress website does not miss out on the SEO benefits of an XML sitemap.

However, it is not very flexible, and you cannot easily control what to add or remove from your XML sitemaps.

Luckily, almost all top WordPress SEO plugins come with their own sitemap functionality. These sitemaps are better, and you can control which content to remove or exclude from your WordPress XML sitemaps.

Method 2. Creating an XML Sitemap in WordPress using All in One SEO

The easiest way to create an XML sitemap in WordPress is by using the All in One SEO plugin for WordPress.

It is the best WordPress SEO plugin on the market offering you a comprehensive set of tools to optimize your blog posts for SEO.

First, you need to install and activate the All in One SEO plugin. For more details, see our step by step guide on how to install a WordPress plugin.

Note: Sitemap feature is also available in AIOSEO Free version. However to get advanced news sitemap and video sitemaps, you’ll need the Pro version.

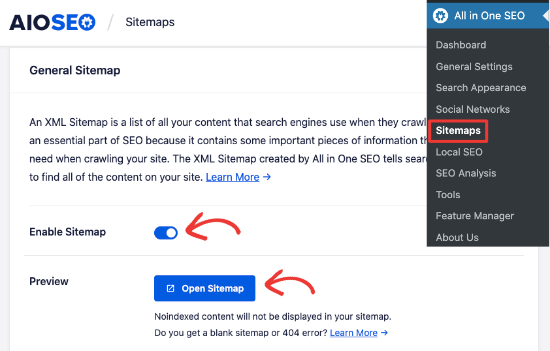

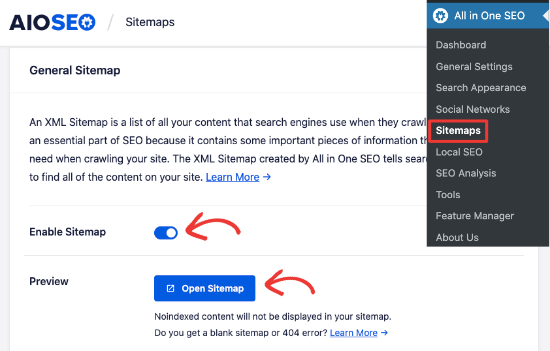

Upon activation, go to the All in One SEO » Sitemaps page to review sitemap settings.

By default, All in One SEO will enable the Sitemap feature for you and replace the basic WordPress sitemaps.

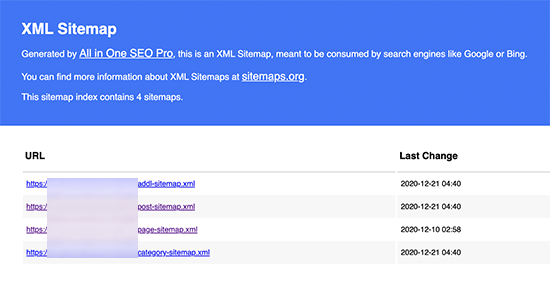

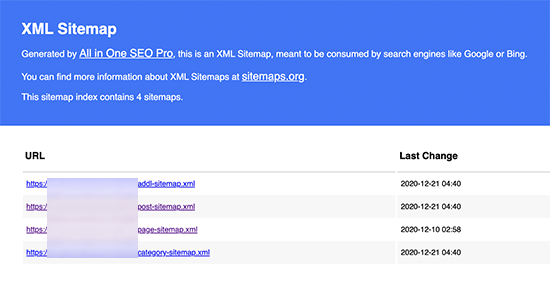

You can click on the ‘Open Sitemap’ button to preview it to see what it looks like. You can also view your sitemap by adding ‘sitemap.xml’ to the URL such as www.example.com/sitemap.xml.

As a beginner, you don’t need to do anything as the default settings would work for all kinds of websites, blogs, and online stores.

However, you can customize the sitemap settings to control what you want to include in your XML sitemap.

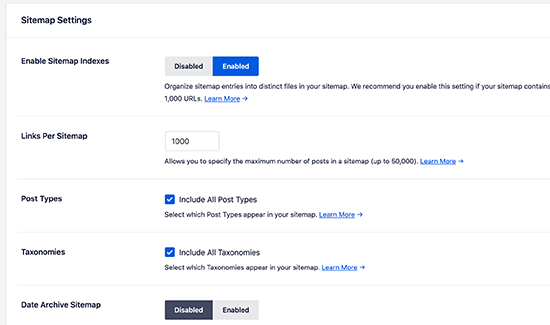

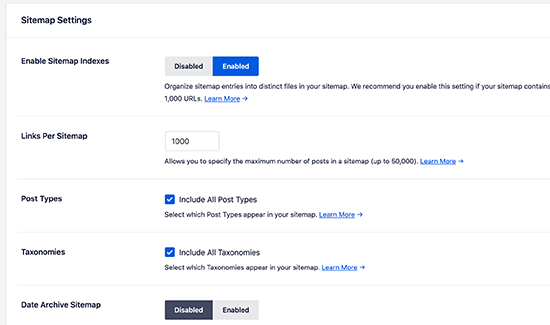

Simply scroll down to the Sitemap settings section.

This section gives you options to manage sitemap indexes, include or exclude post types, taxonomies (categories and tags). You can also enable XML sitemaps for date-based archives and author archives.

All in One SEO automatically includes all your WordPress content in XML sitemaps. However, what if you have stand-alone pages like a contact form, a landing page, or Shopify store pages that are not part of WordPress?

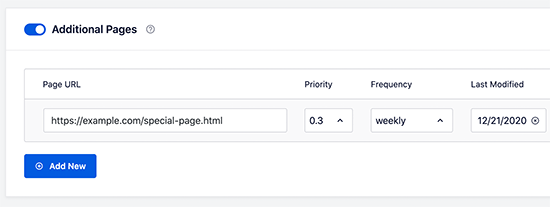

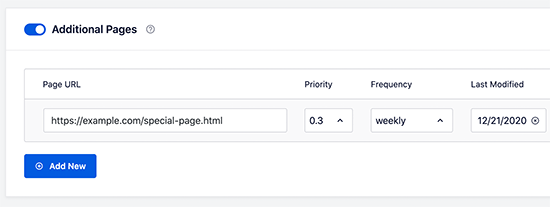

Well, AIOSEO is the only plugin that lets you add external pages in your WordPress sitemap. Simply scroll to the Additional Pages section and turn it on. This will show you a form where you can add any custom pages that you want to include.

You simply need to add the URL of the page that you want to include and then set a priority where 0.0 is the lowest and 1.0 is the highest, if you are unsure then we recommend using 0.3.

Next, choose the frequency of updates and the last modified date for the page.

You can click on the ‘Add New’ button if you need to add more pages.

Don’t forget to click on the ‘Save Changes’ button to store your settings.

Excluding Specific Posts / Pages from your XML Sitemap

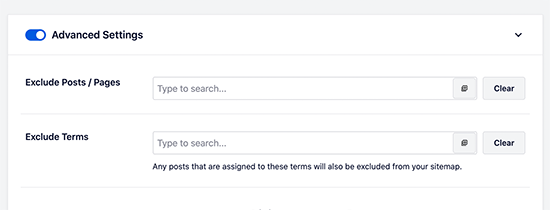

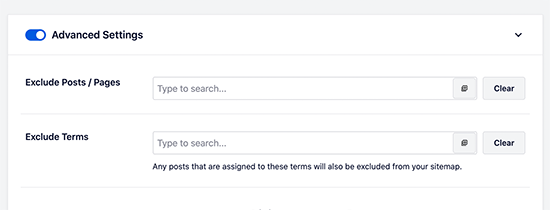

All in One SEO allows you to exclude any post or page from your XML Sitemaps. You can do this by clicking on the Advanced Settings section under the All in One SEO » Sitemaps page.

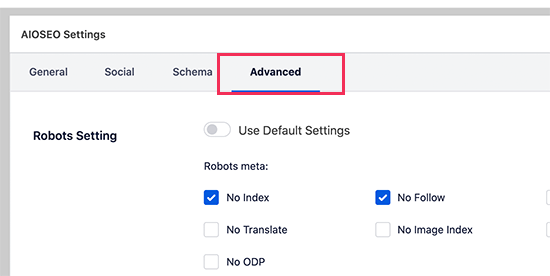

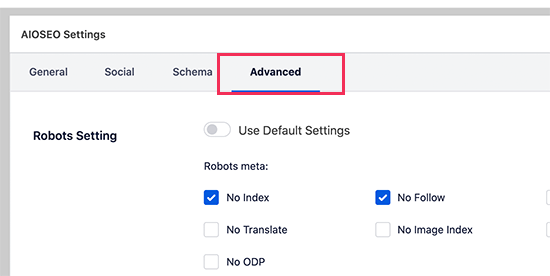

You can also remove a post or page from your XML sitemaps by making it no-index and no-follow. This will block search engines from showing that content in search results.

Simply edit the post or page that you want to exclude and scroll down to the AIOSEO Settings box below the editor.

From here you need to switch to the Advanced tab and check the boxes next to ‘No Index’ and ‘No Follow’ options.

Creating Additional Sitemaps

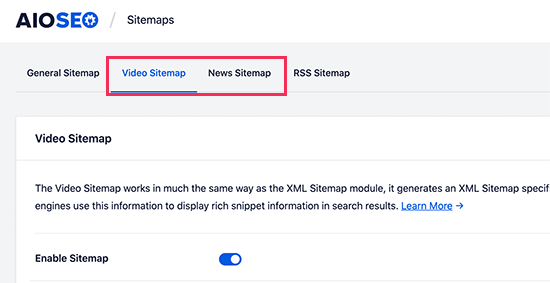

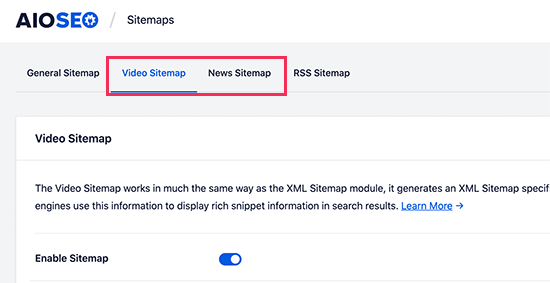

All in One SEO allows you to create additional sitemaps like a video sitemap or a news sitemap.

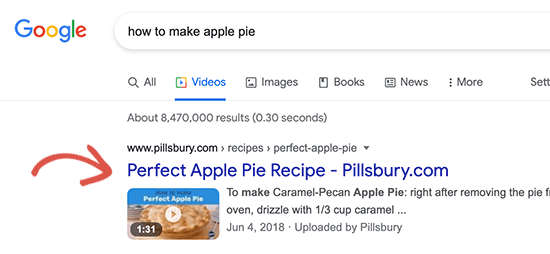

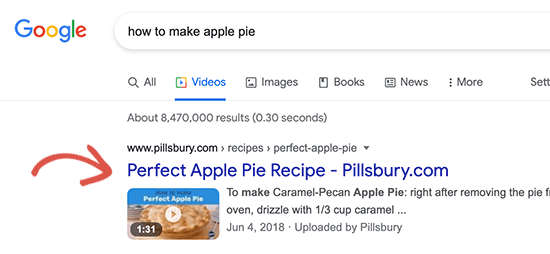

You can create a video sitemap if you regularly embed videos in your blog posts or pages. It allows search engines to display posts in search and video search results along with a video thumbnail.

You can also create a News sitemap if you run a news website and want to appear in Google News search results.

Simply go to All in One SEO » Sitemaps and switch to the Video Sitemap or News Sitemap tabs to generate these sitemaps.

Overall, AIOSEO is the best WordPress plugin because it gives you all the flexibility and powerful features at a very affordable price.

Method 3. Creating an XML Sitemap in WordPress using Yoast SEO

If you are using Yoast SEO as your WordPress SEO plugin, then it also automatically turns on XML sitemaps for you.

First, you need to install and activate the Yoast SEO plugin. For more details, see our step by step guide on how to install a WordPress plugin.

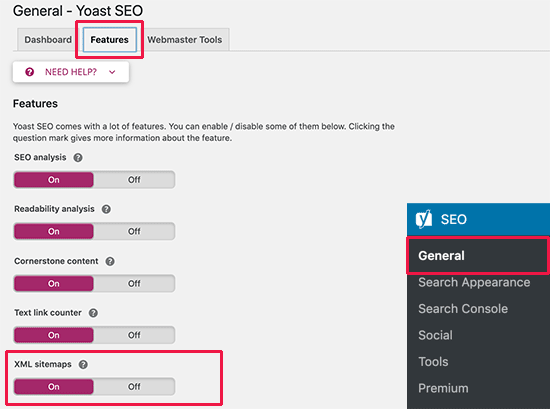

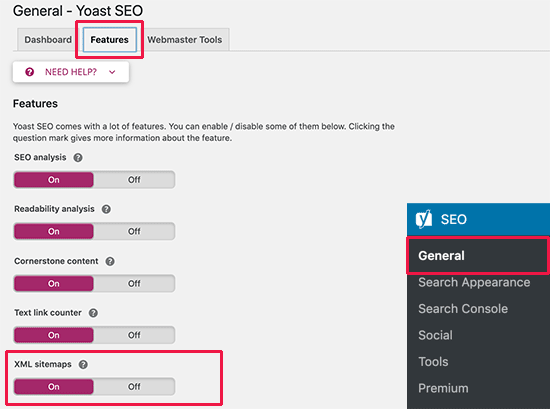

Upon activation, go to SEO » General page and switch to the ‘Features’ tab. From here, you need to scroll down to the ‘XML Sitemap’ option and make sure that it is turned on.

Next, click on the save changes button to store your changes.

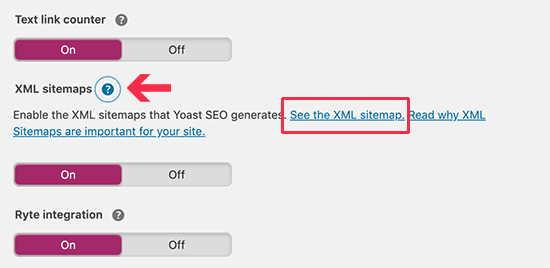

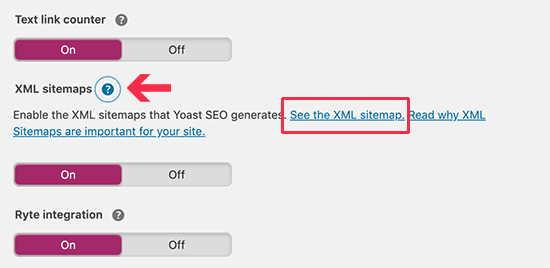

To verify that Yoast SEO has created an XML Sitemap, you can click on the question mark icon next to the XML Sitemap option on the page.

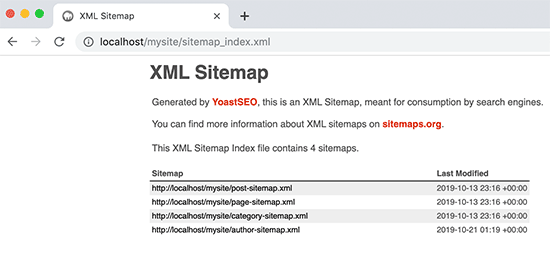

After that, click on the ‘See the XML Sitemap’ link to view your live XML sitemap generated by Yoast SEO.

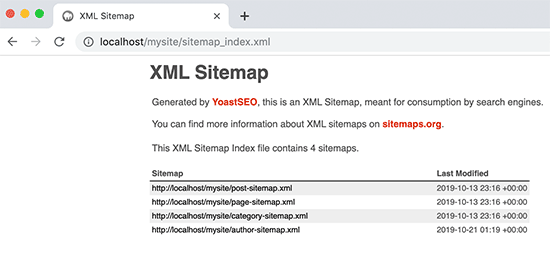

You can also find your XML sitemap by simply adding sitemap_index.xml at the end of your website address. For example:

https://www.example.com/sitemap_index.xml

Yoast SEO creates multiple sitemaps for different types of content. By default, it will generate sitemaps for posts, pages, author, and categories.

How to Submit Your XML Sitemap to Search Engines

Search engines are quite smart in finding a sitemap. Whenever you publish new content, a ping is sent to Google and Bing to inform them about changes in your sitemap.

However, we recommend that you submit the sitemap manually to ensure that search engines can find it.

Submitting Your XML Sitemap to Google

Google Search Console is a free tool offered by Google to help website owners monitor and maintain their site’s presence in Google search results.

Adding your sitemap to Google Search Console helps it quickly discover your content even if your website is brand new.

First, you need to visit the Google Search Console website and sign up for an account.

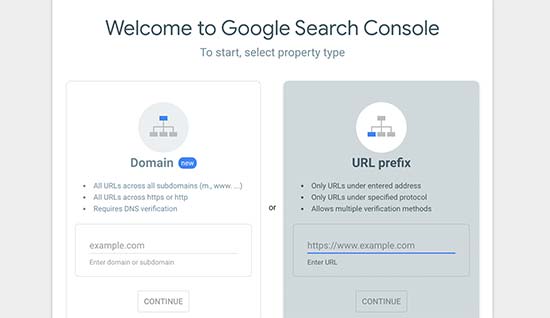

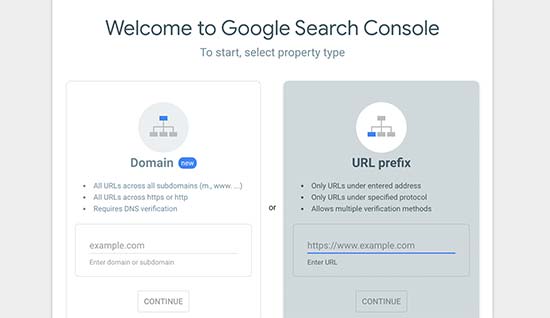

After that, you will be asked to select a property type. You can choose a domain or a URL prefix. We recommend choosing URL prefix as it is easier to setup.

Enter your website’s URL and then click on the continue button.

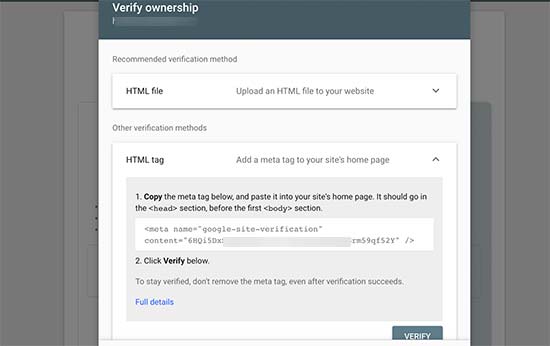

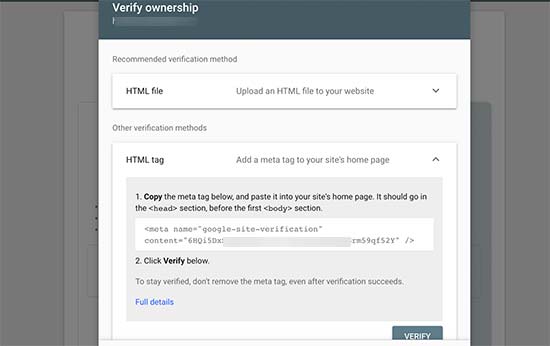

Next, you will be asked to verify ownership of the website. You will see multiple methods to do that, we recommend using the HTML tag method.

Simply copy the code on the screen and then go to the admin area of your WordPress website.

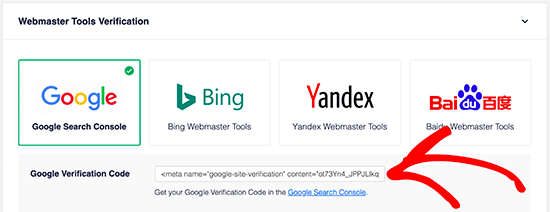

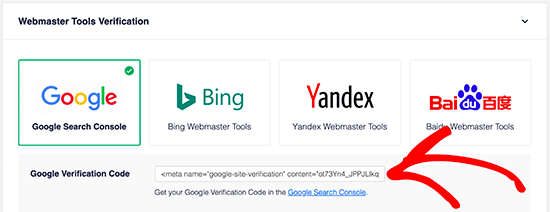

If you’re using AIOSEO, then it comes with easy webmaster tools verification. Simply go to All in One SEO » General Settings and then click the Webmaster Tools tab. After that, you can enter the code from Google there.

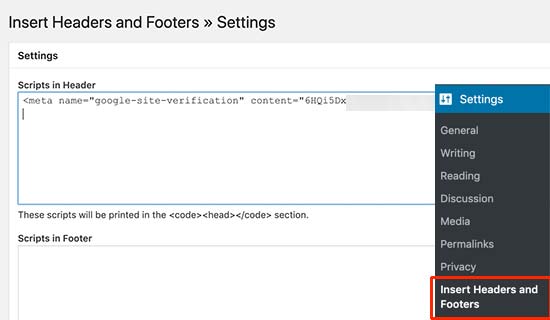

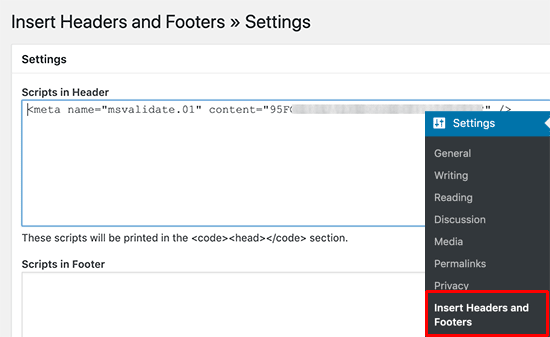

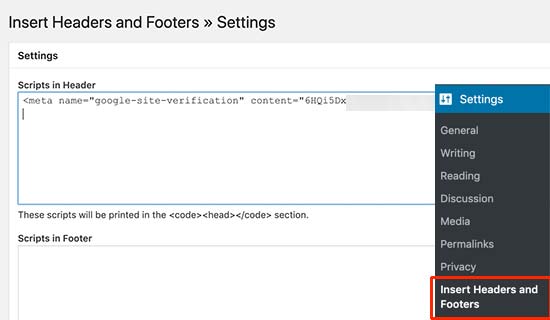

If you’re not using AIOSEO, then you need to install and activate the Insert Headers and Footers plugin. For more details, see our step by step guide on how to install a WordPress plugin.

Upon activation, you need to visit Settings » Insert Headers and Footers page and add the code you copied earlier in the ‘Scripts in Header’ box.

Don’t forget to click on the save button to store your changes.

Now, switch back to the Google Search Console tab and click on the ‘Verify’ button.

Google will check for verification code on your site and then add it to your Google Search Console account.

Note: If the verification is unsuccessful, then please make sure to clear your cache and then try again.

Now that you have added your website, let’s add your XML sitemap as well.

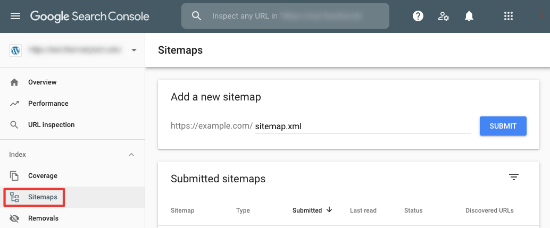

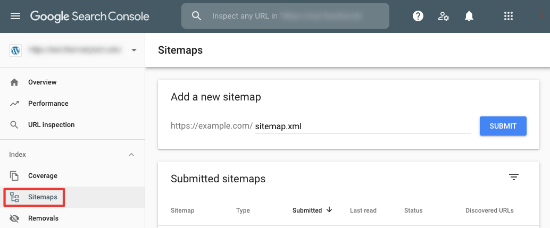

From your account dashboard, you need to click on ‘Sitemaps’ from the left column.

After that, you need to add the last part of your sitemap URL under the ‘Add new sitemap’ section and click the Submit button.

Google will now add your sitemap URL to your Google Search Console.

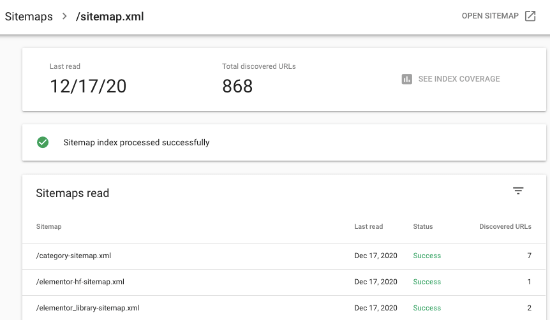

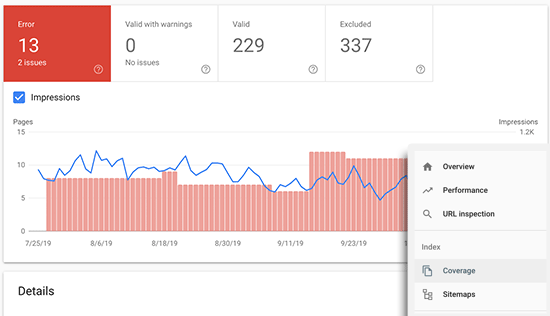

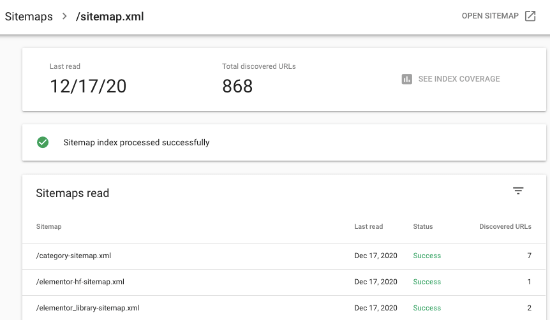

It will take Google some time to crawl your website. After a while, you would be able to see basic sitemap stats.

This information includes the number of links Google found in your sitemap, how many of them got indexed, a ratio of images to web pages, and more.

Submitting Your XML Sitemap to Bing

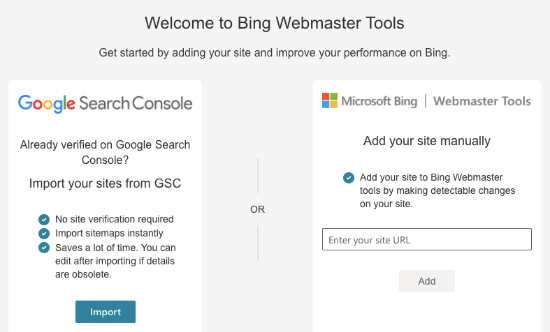

Similar to Google Search Console, Bing also offers Bing Webmaster Tools to help website owners monitor their website in the Bing search engine.

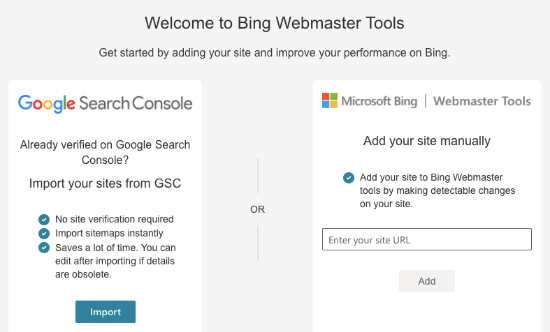

To add your sitemap to Bing, you need to visit the Bing Webmaster Tools website. Here, you’ll see two options to add your site. You can either import your site from Google Search Console or add it manually.

If you’ve already added your site to Google Search Console, we suggest importing your site. It saves time as your sitemap will automatically be imported for you.

If you choose to add your site manually, you need to enter your site’s URL and then verify the site.

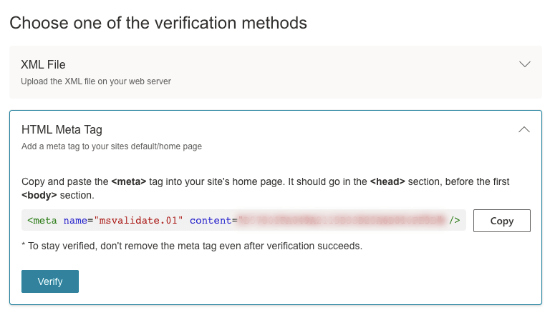

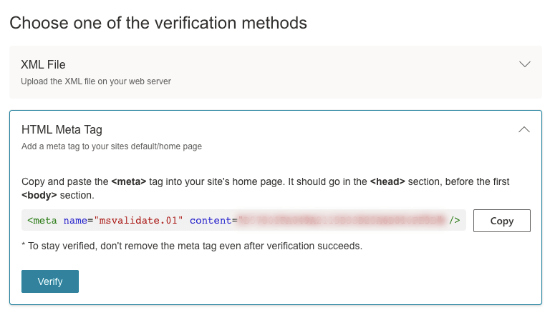

Bing will now ask you to verify the ownership of your website and will show you several methods to do that.

We recommend using the Meta tag method. Simply copy the meta tag line from the page and head over to your WordPress admin area.

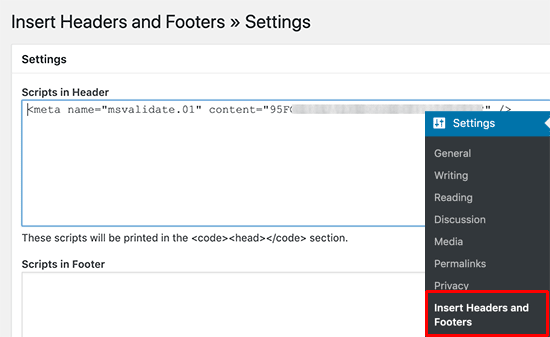

Now, install and activate the Insert Headers and Footers plugin on your website.

Upon activation, you need to visit Settings » Insert Headers and Footers page and add the code you copied earlier in the ‘Scripts in header’ box.

Don’t forget to click on the Save button to store your changes.

How to Utilize XML Sitemaps to Grow Your Website?

Now that you have submitted the XML sitemap to Google, let’s take a look at how to utilize it for your website.

First, you need to keep in mind that the XML sitemap does not improve your search rankings. However, it does help search engines find content, adjust crawl rate, and improve your website’s visibility in search engines.

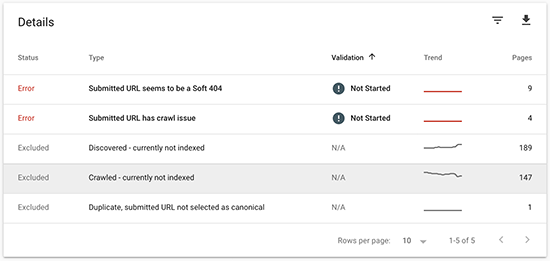

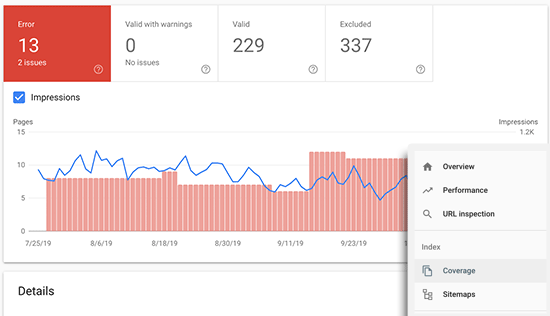

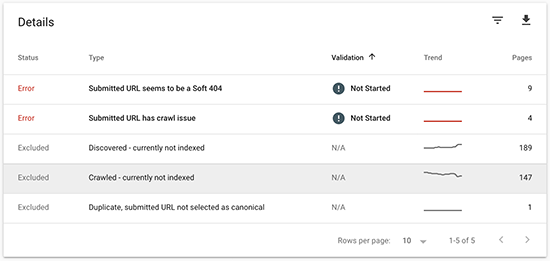

You need to keep an eye on your sitemap stats in Google Search Console. It can show you crawl errors and the pages excluded from search coverage.

Below the charts, you can click on the tables to view actual URLs excluded or not indexed by Google.

Normally, Google may decide to skip duplicate content, pages with no content or very little content, and pages excluded by your website’s robots.txt file or meta tags.

However, if you have an unusually high number of excluded pages, then you may want to check your SEO plugin settings to make sure that you are not blocking any content.

For more details, see our complete Google Search Console guide for beginners.

We hope this article helped answer all your questions about XML sitemaps and how to create an XML sitemap for your WordPress site. You may also want to see our guide on how to quickly increase your website traffic with step by step tips, and our comparison of the best keyword research tools to write better content.

If you liked this article, then please subscribe to our YouTube Channel for WordPress video tutorials. You can also find us on Twitter and Facebook.

The post What is an XML Sitemap? How to Create a Sitemap in WordPress? appeared first on WPBeginner.