In back-end development, storage is a common part of the job. Application data is stored in databases, files in object storage, transient data in caches… there are seemingly endless possibilities for storing any sort of data. But data storage isn’t limited only to the back end. The front end (the browser) is equipped with many options to store data as well. We can boost our application performance, save user preferences, keep the application state across multiple sessions, or even different computers, by utilizing this storage.

In this article, we will go through the different possibilities to store data in the browser. We will cover three use cases for each method to grasp the pros and cons. In the end, you will be able to decide what storage is the best fit for your use case. So let’s start!

The localStorage API

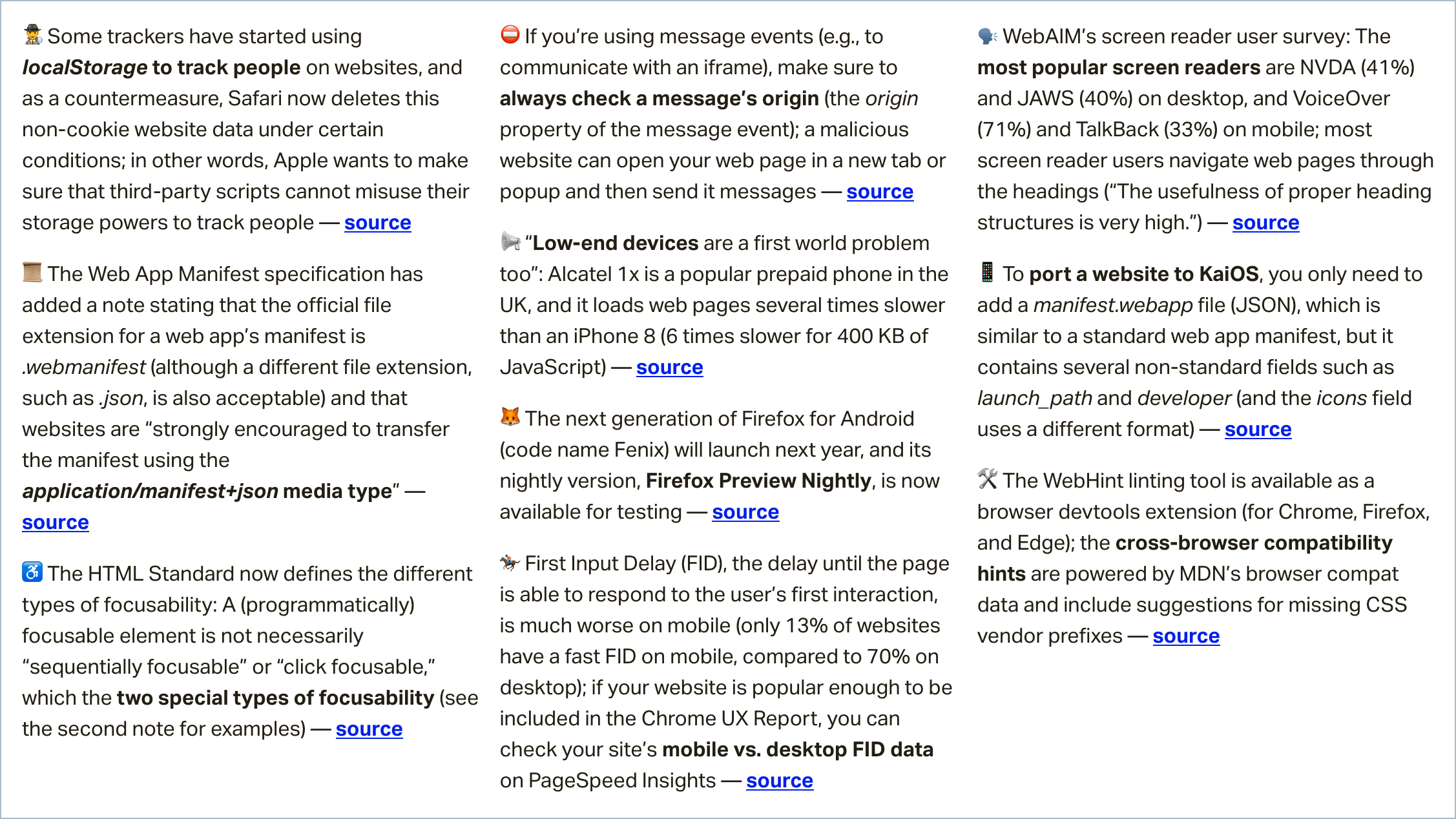

localStorage is one of the most popular storage options in the browser and the go-to for many developers. The data is stored across sessions, never shared with the server, and is available for all pages under the same protocol and domain. Storage is limited to ~5MB.

Surprisingly, the Google Chrome team doesn’t recommend using this option as it blocks the main thread and is not accessible to web workers and service workers. They launched an experiment, KV Storage, as a better version, but it was just a trial that doesn’t seem to have gone anywhere just yet.

The localStorage API is available as window.localStorage and can save only UTF-16 strings. We must make sure to convert data to strings before saving it into localStorage. The main three functions are:

setItem('key', 'value')getItem('key')removeItem('key')

They’re all synchronous, which makes it simple to work with, but they block the main thread.

It’s worth mentioning that localStorage has a twin called sessionStorage. The only difference is that data stored in sessionStorage will last only for the current session, but the API is the same.

Let’s see it in action. The first example demonstrates how to use localStorage for storing the user’s preferences. In our case, it’s a boolean property that turns on or off the dark theme of our site.

You can check the checkbox and refresh the page to see that the state is saved across sessions. Take a look at the save and load functions to see how I convert the value to string and how I parse it. It’s important to remember that we can store only strings.

This second example loads Pokémon names from the PokéAPI.

We send a GET request using fetch and list all the names in a ul element. Upon getting the response, we cache it in the localStorage so our next visit can be much faster or even work offline. We have to use JSON.stringify to convert the data to string and JSON.parse to read it from the cache.

In this last example, I demonstrate a use case where the user can browse through different Pokémon pages, and the current page is saved for the next visits.

The issue with localStorage, in this case, is that the state is saved locally. This behavior doesn’t allow us to share the desired page with our friends. Later, we will see how to overcome this issue.

We will use these three examples in the next storage options as well. I forked the Pens and just changed the relevant functions. The overall skeleton is the same for all methods.

The IndexedDB API

IndexedDB is a modern storage solution in the browser. It can store a significant amount of structured data — even files, and blobs. Like every database, IndexedDB indexes the data for running queries efficiently. It’s more complex to use IndexedDB. We have to create a database, tables, and use transactions.

Compared to localStorage , IndexedDB requires a lot more code. In the examples, I use the native API with a Promise wrapper, but I highly recommend using third-party libraries to help you out. My recommendation is localForage because it uses the same localStorage API but implements it in a progressive enhancement manner, meaning if your browser supports IndexedDB, it will use it; and if not, it will fall back to localStorage.

Let’s code, and head over to our user preferences example!

idb is the Promise wrapper that we use instead of working with a low-level events-based API. They’re almost identical, so don’t worry. The first thing to notice is that every access to the database is async, meaning we don’t block the main thread. Compared to localStorage, this is a major advantage.

We need to open a connection to our database so it will be available throughout the app for reading and writing. We give our database a name, my-db, a schema version, 1, and an update function to apply changes between versions. This is very similar to database migrations. Our database schema is simple: only one object store, preferences. An object store is the equivalent of an SQL table. To write or read from the database, we must use transactions. This is the tedious part of using IndexedDB. Have a look at the new save and load functions in the demo.

No doubt that IndexedDB has much more overhead and the learning curve is steeper compared to localStorage. For the key value cases, it might make more sense to use localStorage or a third-party library that will help us be more productive.

Application data, such as in our Pokémon example, is the forte of IndexedDB. You can store hundreds of megabytes and even more in this database. You can store all the Pokémon in IndexedDB and have them available offline and even indexed! This is definitely the one to choose for storing app data.

I skipped the implementation of the third example, as IndexedDB doesn’t introduce any difference in this case compared to localStorage. Even with IndexedDB, the user will still not share the selected page with others or bookmark it for future use. They’re both not the right fit for this use case.

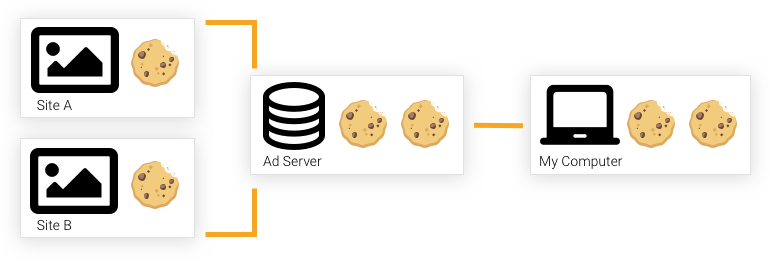

Cookies

Using cookies is a unique storage option. It’s the only storage that is also shared with the server. Cookies are sent as part of every request. It can be when the user browses through pages in our app or when the user sends Ajax requests. This allows us to create a shared state between the client and the server, and also share state between multiple applications in different subdomains. This is not possible by other storage options that are described in this article. One caveat: cookies are sent with every request, which means that we have to keep our cookies small to maintain a decent request size.

The most common use for cookies is authentication, which is out of the scope of this article. Just like the localStorage, cookies can store only strings. The cookies are concatenated into one semicolon-separated string, and they are sent in the cookie header of the request. You can set many attributes for every cookie, such as expiration, allowed domains, allowed pages, and many more.

In the examples, I show how to manipulate the cookies through the client-side, but it’s also possible to change them in your server-side application.

Saving the user’s preferences in a cookie can be a good fit if the server can utilize it somehow. For example, in the theme use case, the server can deliver the relevant CSS file and reduce potential bundle size (in case we’re doing server-side-rendering). Another use case might be to share these preferences across multiple subdomain apps without a database.

Reading and writing cookies with JavaScript is not as straightforward as you might think. To save a new cookie, you need to set document.cookie — check out the save function in the example above. I set the dark_theme cookie and add it a max-age attribute to make sure it will not expire when the tab is closed. Also, I add the SameSite and Secure attributes. These are necessary because CodePen uses iframe to run the examples, but you will not need them in most cases. Reading a cookie requires parsing the cookie string.

A cookie string looks like this:

key1=value1;key2=value2;key3=value3

So, first, we have to split the string by semicolon. Now, we have an array of cookies in the form of key1=value1, so we need to find the right element in the array. In the end, we split by the equal sign and get the last element in the new array. A bit tedious, but once you implement the getCookie function (or copy it from my example :P) you can forget it.

Saving application data in a cookie can be a bad idea! It will drastically increase the request size and will reduce application performance. Also, the server cannot benefit from this information as it’s a stale version of the information it already has in its database. If you use cookies, make sure to keep them small.

The pagination example is also not a good fit for cookies, just like localStorage and IndexedDB. The current page is a temporary state that we would like to share with others, and any of these methods do not achieve it.

URL storage

URL is not a storage, per se, but it’s a great way to create a shareable state. In practice, it means adding query parameters to the current URL that can be used to recreate the current state. The best example would be search queries and filters. If we search the term flexbox on CSS-Tricks, the URL will be updated to https://css-tricks.com/?s=flexbox. See how easy it is to share a search query once we use the URL? Another advantage is that you can simply hit the refresh button to get newer results of your query or even bookmark it.

We can save only strings in the URL, and its maximum length is limited, so we don’t have so much space. We will have to keep our state small. No one likes long and intimidating URLs.

Again, CodePen uses iframe to run the examples, so you cannot see the URL actually changing. Worry not, because all the bits and pieces are there so you can use it wherever you want.

We can access the query string through window.location.search and, lucky us, it can be parsed using the URLSearchParams class. No need to apply any complex string parsing anymore. When we want to read the current value, we can use the get function. When we want to write, we can use set. It’s not enough to only set the value; we also need to update the URL. This can be done using history.pushState or history.replaceState, depending on the behavior we want to accomplish.

I wouldn’t recommend saving a user’s preferences in the URL as we will have to add this state to every URL the user visits, and we cannot guarantee it; for example, if the user clicks on a link from Google Search.

Just like cookies, we cannot save application data in the URL as we have minimal space. And even if we did manage to store it, the URL will be long and not inviting to click. Might look like a phishing attack of sorts.

Just like our pagination example, the temporary application state is the best fit for the URL query string. Again, you cannot see the URL changes, but the URL updates with the ?page=x query parameter every time you click on a page. When the web page loads, it looks for this query parameter and fetches the right page accordingly. Now we can share this URL with our friends so they can enjoy our favorite Pokémon.

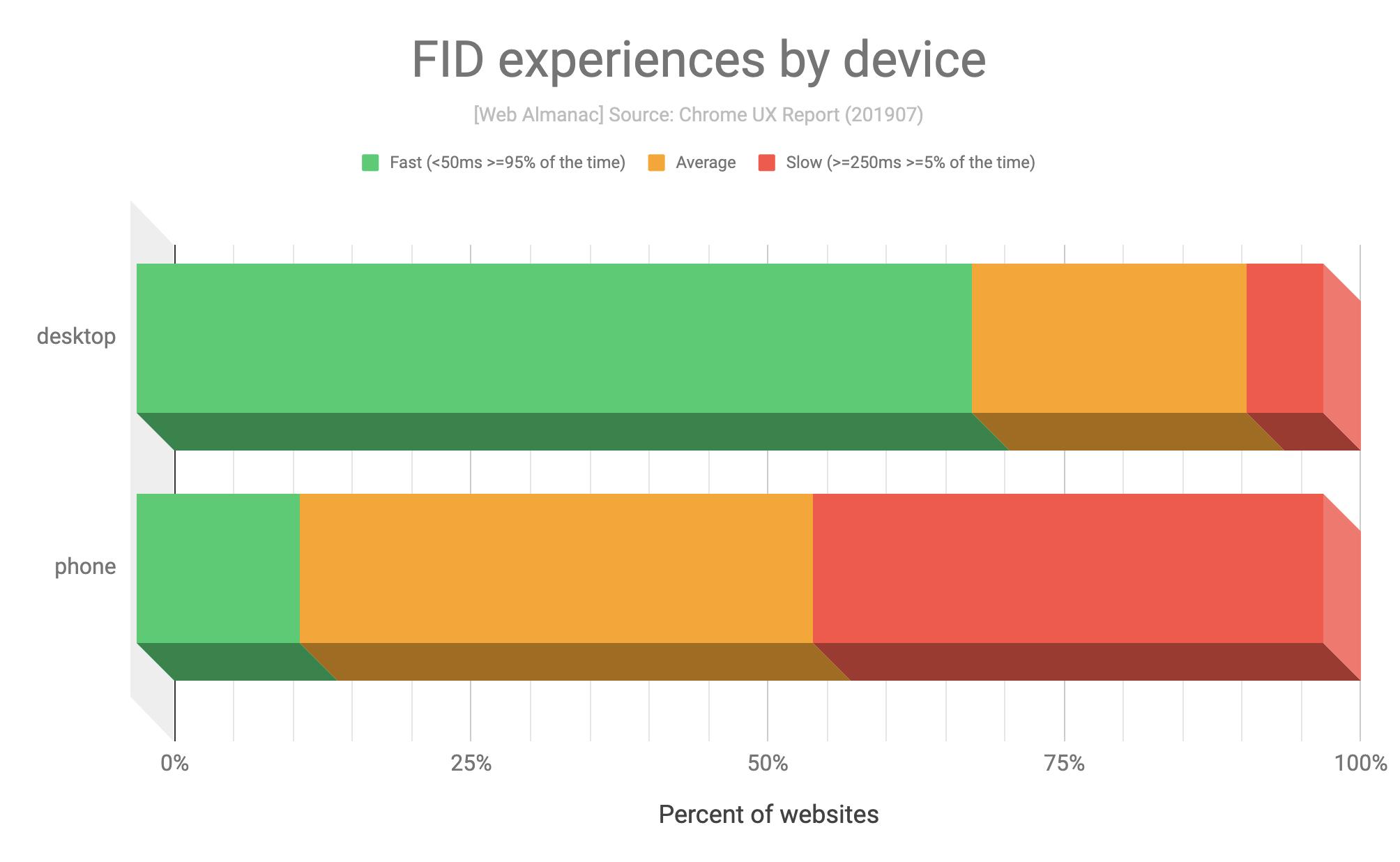

Cache API

Cache API is a storage for the network level. It is used to cache network requests and their responses. The Cache API fits perfectly with service workers. A service worker can intercept every network request, and using the Cache API, it can easily cache both the requests. The service worker can also return an existing cache item as a network response instead of fetching it from the server. By doing so, you can reduce network load times and make your application work even when offline. Originally, it was created for service workers but in modern browsers the Cache API is available also in window, iframe, and worker contexts as-well. It’s a very powerful API that can improve drastically the application user experience.

Just like IndexedDB the Cache API storage is not limited and you can store hundreds of megabytes and even more if you need to. The API is asynchronous so it will not block your main thread. And it’s accessible through the global property caches.

To read more about the Cache API, the Google Chrome team has made a great tutorial.

Chris created an awesome Pen with a practical example of combining service workers and the Cache API.

Bonus: Browser extension

If you build a browser extension, you have another option to store your data. I discovered it while working on my extension, daily.dev. It’s available via chrome.storage or browser.storage, if you use Mozilla’s polyfill. Make sure to request a storage permission in your manifest to get access.

There are two types of storage options, local and sync. The local storage is self-explanatory; it means it isn’t shared and kept locally. The sync storage is synced as part of the Google account and anywhere you install the extension with the same account this storage will be synced. Pretty cool feature if you ask me. Both have the same API so it’s super easy to switch back-and-forth, if needed. It’s async storage so it doesn’t block the main thread like localStorage. Unfortunately, I cannot create a demo for this storage option as it requires a browser extension but it’s pretty simple to use, and almost like localStorage. For more information about the exact implementation, refer to Chrome docs.

Conclusion

The browser has many options we can utilize to store our data. Following the Chrome team’s advice, our go-to storage should be IndexedDB. It’s async storage with enough space to store anything we want. localStorage is not encouraged, but is easier to use than IndexedDB. Cookies are a great way to share the client state with the server but are mostly used for authentication.

If you want to create pages with a shareable state such as a search page, use the URL’s query string to store this information. Lastly, if you build an extension, make sure to read about chrome.storage.

The post A Primer on the Different Types of Browser Storage appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.