Visit The Site For More...

Knobs for Demos

CodePen is full of prototypes and loaded with full-blown art. Generative art is common, since hey, we’re working with code anyway, might as well make some of the code randomized and adjustable. There is a great project that has been around years and years that is purpose-built for giving users a UI to change values on-the-fly called dat.GUI. I once blogged about it right here on the CodePen Blog because I wanted to showcase how useful it can be for generative art Pens. While dat.GUI is still pretty cool and perfectly usable, there is a new player on the block.

Introducing Knobs by Yair Even Or! Demo first:

To me, the API and configuration is really clear and usable. I like how it is also modernized by using stuff like <input type="range"> for the sliders rather than re-inventing that. And the focus on changing CSS custom properties is very clever. Plus, you can style the controls themselves.

I snagged it and updated my Gray Burst idea from the other day to have a stroke-width knob:

I wish every generative art Pen had knobs!

The post Knobs for Demos appeared first on CodePen Blog.

Parsing Markdown into an Automated Table of Contents

A table of contents is a list of links that allows you to quickly jump to specific sections of content on the same page. It benefits long-form content because it shows the user a handy overview of what content there is with a convenient way to get there.

This tutorial will show you how to parse long Markdown text to HTML and then generate a list of links from the headings. After that, we will make use of the Intersection Observer API to find out which section is currently active, add a scrolling animation when a link is clicked, and finally, learn how Vue’s <transition-group> allow us to create a nice animated list depending on which section is currently active.

Parsing Markdown

On the web, text content is often delivered in the form of Markdown. If you haven’t used it, there are lots of reasons why Markdown is an excellent choice for text content. We are going to use a markdown parser called marked, but any other parser is also good.

We will fetch our content from a Markdown file on GitHub. After we loaded our Markdown file, all we need to do is call the marked(<markdown>, <options>) function to parse the Markdown to HTML.

async function fetchAndParseMarkdown() {

const url = 'https://gist.githubusercontent.com/lisilinhart/e9dcf5298adff7c2c2a4da9ce2a3db3f/raw/2f1a0d47eba64756c22460b5d2919d45d8118d42/red_panda.md'

const response = await fetch(url)

const data = await response.text()

const htmlFromMarkdown = marked(data, { sanitize: true });

return htmlFromMarkdown

}After we fetch and parse our data, we will pass the parsed HTML to our DOM by replacing the content with innerHTML.

async function init() {

const $main = document.querySelector('#app');

const htmlContent = await fetchAndParseMarkdown();

$main.innerHTML = htmlContent

}

init();Generating a list of heading links

Now that we’ve generated the HTML, we need to transform our headings into a clickable list of links. To find the headings, we will use the DOM function querySelectorAll('h1, h2'), which selects all <h1> and <h2> elements within our markdown container. Then we’ll run through the headings and extract the information we need: the text inside the tags, the depth (which is 1 or 2), and the element ID we can use to link to each respective heading.

function generateLinkMarkup($contentElement) {

const headings = [...$contentElement.querySelectorAll('h1, h2')]

const parsedHeadings = headings.map(heading => {

return {

title: heading.innerText,

depth: heading.nodeName.replace(/\D/g,''),

id: heading.getAttribute('id')

}

})

console.log(parsedHeadings)

}This snippet results in an array of elements that looks like this:

[

{title: "The Red Panda", depth: "1", id: "the-red-panda"},

{title: "About", depth: "2", id: "about"},

// ...

]After getting the information we need from the heading elements, we can use ES6 template literals to generate the HTML elements we need for the table of contents.

First, we loop through all the headings and create <li> elements. If we’re working with an <h2> with depth: 2, we will add an additional padding class, .pl-4, to indent them. That way, we can display <h2> elements as indented subheadings within the list of links.

Finally, we join the array of <li> snippets and wrap it inside a <ul> element.

function generateLinkMarkup($contentElement) {

// ...

const htmlMarkup = parsedHeadings.map(h => `

<li class="${h.depth > 1 ? 'pl-4' : ''}">

<a href="#${h.id}">${h.title}</a>

</li>

`)

const finalMarkup = `<ul>${htmlMarkup.join('')}</ul>`

return finalMarkup

}That’s all we need to generate our link list. Now, we will add the generated HTML to the DOM.

async function init() {

const $main = document.querySelector('#content');

const $aside = document.querySelector('#aside');

const htmlContent = await fetchAndParseMarkdown();

$main.innerHTML = htmlContent

const linkHtml = generateLinkMarkup($main);

$aside.innerHTML = linkHtml

}Adding an Intersection Observer

Next, we need to find out which part of the content we’re currently reading. Intersection Observers are the perfect choice for this. MDN defines Intersection Observer as follows:

The Intersection Observer API provides a way to asynchronously observe changes in the intersection of a target element with an ancestor element or with a top-level document’s viewport.

So, basically, they allow us to observe the intersection of an element with the viewport or one of its parent’s elements. To create one, we can call a new IntersectionObserver(), which creates a new observer instance. Whenever we create a new observer, we need to pass it a callback function that is called when the observer has observed an intersection of an element. Travis Almand has a thorough explanation of the Intersection Observer you can read, but what we need for now is a callback function as the first parameter and an options object as the second parameter.

function createObserver() {

const options = {

rootMargin: "0px 0px -200px 0px",

threshold: 1

}

const callback = () => { console.log("observed something") }

return new IntersectionObserver(callback, options)

}The observer is created, but nothing is being observed at the moment. We will need to observe the heading elements in our Markdown, so let’s loop over them and add them to the observer with the observe() function.

const observer = createObserver()

$headings.map(heading => observer.observe(heading))Since we want to update our list of links, we will pass it to the observer function as a $links parameter, because we don’t want to re-read the DOM on every update for performance reasons. In the handleObserver function, we find out whether a heading is intersecting with the viewport, then obtain its id and pass it to a function called updateLinks which handles updating the class of the links in our table of contents.

function handleObserver(entries, observer, $links) {

entries.forEach((entry)=> {

const { target, isIntersecting, intersectionRatio } = entry

if (isIntersecting && intersectionRatio >= 1) {

const visibleId = `#${target.getAttribute('id')}`

updateLinks(visibleId, $links)

}

})

}Let’s write the function to update the list of links. We need to loop through all links, remove the .is-active class if it exists, and add it only to the element that’s actually active.

function updateLinks(visibleId, $links) {

$links.map(link => {

let href = link.getAttribute('href')

link.classList.remove('is-active')

if(href === visibleId) link.classList.add('is-active')

})

}The end of our init() function creates an observer, observes all the headings, and updates the links list so the active link is highlights when the observer notices a change.

async function init() {

// Parsing Markdown

const $aside = document.querySelector('#aside');

// Generating a list of heading links

const $headings = [...$main.querySelectorAll('h1, h2')];

// Adding an Intersection Observer

const $links = [...$aside.querySelectorAll('a')]

const observer = createObserver($links)

$headings.map(heading => observer.observe(heading))

}Scroll to section animation

The next part is to create a scrolling animation so that, when a link in the table of contents is clicked, the user is scrolled to the heading position rather abruptly jumping there. This is often called smooth scrolling.

Scrolling animations can be harmful if a user prefers reduced motion, so we should only animate this scrolling behavior if the user hasn’t specified otherwise. With window.matchMedia('(prefers-reduced-motion)'), we can read the user preference and adapt our animation accordingly. That means we need a click event listener on each link. Since we need to scroll to the headings, we will also pass our list of $headings and the motionQuery.

const motionQuery = window.matchMedia('(prefers-reduced-motion)');

$links.map(link => {

link.addEventListener("click",

(evt) => handleLinkClick(evt, $headings, motionQuery)

)

})Let’s write our handleLinkClick function, which is called whenever a link is clicked. First, we need to prevent the default behavior of links, which would be to jump directly to the section. Then we’ll read the href attribute of the clicked link and find the heading with the corresponding id attribute. With a tabindex value of -1 and focus(), we can focus our heading to make the users aware of where they jumped to. Finally, we add the scrolling animation by calling scroll() on our window.

Here is where our motionQuery comes in. If the user prefers reduced motion, the behavior will be instant; otherwise, it will be smooth. The top option adds a bit of scroll margin to the top of the headings to prevent them from sticking to the very top of the window.

function handleLinkClick(evt, $headings, motionQuery) {

evt.preventDefault()

let id = evt.target.getAttribute("href").replace('#', '')

let section = $headings.find(heading => heading.getAttribute('id') === id)

section.setAttribute('tabindex', -1)

section.focus()

window.scroll({

behavior: motionQuery.matches ? 'instant' : 'smooth',

top: section.offsetTop - 20

})

}Animate the list of links

For the last part, we will make use of Vue’s <transition-group>, which is very useful for list transitions. Here is Sarah Drasner’s excellent intro to Vue transitions if you’ve never worked with them before. They are especially great because they provide us with animation lifecycle hooks with easy access to CSS animations.

Vue automatically attaches CSS classes for us when an element is added (v-enter) or removed (v-leave) from a list, and also with classes for when the animation is active (v-enter-active and v-leave-active). This is perfect for our case because we can vary the animation when subheadings are added or removed from our list. To use them, we will need wrap our <li> elements in our table of contents with an <transition-group> element. The name attribute of the <transition-group> defines how the CSS animations will be called, the tag attribute should be our parent <ul> element.

<transition-group name="list" tag="ul">

<li v-for="(item, index) in activeHeadings" v-bind:key="item.id">

<a :href="item.id">

{{ item.text }}

</a>

</li>

</transition-group>Now we need to add the actual CSS transitions. Whenever an element is entering or leaving it, should animate from not visible (opacity: 0) and moved a bit to the bottom (transform: translateY(10px)).

.list-enter, .list-leave-to {

opacity: 0;

transform: translateY(10px);

}Then we define what CSS property we want to animate. For performance reasons, we only want to animate the transform and the opacity properties. CSS allows us to chain the transitions with different timings: the transform should take 0.8 seconds and the fading only 0.4s.

.list-leave-active, .list-move {

transition: transform 0.8s, opacity 0.4s;

}Then we want to add a bit of a delay when a new element is added, so the subheadings fade in after the parent heading moved up or down. We can make use of the v-enter-active hook to do that:

.list-enter-active {

transition: transform 0.8s ease 0.4s, opacity 0.4s ease 0.4s;

}Finally, we can add absolute positioning to the elements that are leaving to avoid sudden jumps when the other elements are animating:

.list-leave-active {

position: absolute;

}Since the scrolling interaction is fading elements out and in, it’s advisable to debounce the scrolling interaction in case someone is scrolling very quickly. By debouncing the interaction we can avoid unfinished animations overlapping other animations. You can either write your own debouncing function or simply use the lodash debounce function. For our example the simplest way to avoid unfinished animation updates is to wrap the Intersection Observer callback function with a debounce function and pass the debounced function to the observer.

const debouncedFunction = _.debounce(this.handleObserver)

this.observer = new IntersectionObserver(debouncedFunction,options)Here’s the final demo

Again, a table of contents is a great addition to any long-form content. It helps make clear what content is covered and provides quick access to specific content. Using the Intersection Observer and Vue’s list animations on top of it can help to make a table of contents even more interactive and even allow it to serve as an indication of reading progress. But even if you only add a list of links, it will already be a great feature for the user reading your content.

The post Parsing Markdown into an Automated Table of Contents appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.

What’s New In Vue 3?

With the release of Vue 3, developers have to make the upgrade from Vue 2 as it comes with a handful of new features that are super helpful in building easy-to-read and maintainable components and improved ways to structure our application in Vue. We’re going to be taking a look at some of these features in this article.

At the end of this tutorial, the readers will;

- Know about

provide / injectand how to use it. - Have a basic understanding of Teleport and how to use it.

- Know about Fragments and how to go about using them.

- Know about the changes made to the Global Vue API.

- Know about the changes made to the Events API.

This article is aimed at those that have a proper understanding of Vue 2.x. You can find all the code used in this example in GitHub.

provide / inject

In Vue 2.x, we had props that made it easy to pass data (string, arrays, objects, etc) from a parent component directly to its children component. But during development, we often found instances where we needed to pass data from the parent component to a deeply nested component which was more difficult to do with props. This resulted in the use of Vuex Store, Event Hub, and sometimes passing data through the deeply nested components. Let’s look at a simple app;

It is important to note that Vue 2.2.0 also came with provide / inject which was not recommended to use in generic application code.

# parentComponent.vue

<template>

<div class="home">

<img alt="Vue logo" src="../assets/logo.png" />

<HelloWorld msg="Vue 3 is liveeeee!" :color="color" />

<select name="color" id="color" v-model="color">

<option value="" disabled selected> Select a color</option>

<option :value="color" v-for="(color, index) in colors" :key="index">{{

color

}}</option></select

>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import HelloWorld from "@/components/HelloWorld.vue";

export default {

name: "Home",

components: {

HelloWorld,

},

data() {

return {

color: "",

colors: ["red", "blue", "green"],

};

},

};

</script>

# childComponent.vue

<template>

<div class="hello">

<h1>{{ msg }}</h1>

<color-selector :color="color"></color-selector>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import colorSelector from "@/components/colorComponent.vue";

export default {

name: "HelloWorld",

components: {

colorSelector,

},

props: {

msg: String,

color: String,

},

};

</script>

<!-- Add "scoped" attribute to limit CSS to this component only -->

<style scoped>

h3 {

margin: 40px 0 0;

}

ul {

list-style-type: none;

padding: 0;

}

li {

display: inline-block;

margin: 0 10px;

}

a {

color: #42b983;

}

</style>

# colorComponent.vue

<template>

<p :class="[color]">This is an example of deeply nested props!</p>

</template>

<script>

export default {

props: {

color: String,

},

};

</script>

<style>

.blue {

color: blue;

}

.red {

color: red;

}

.green {

color: green;

}

</style>

Here, we have a landing page with a dropdown containing a list of colors and we’re passing the selected color to childComponent.vue as a prop. This child component also has a msg prop that accepts a text to display in the template section. Finally, this component has a child component (colorComponent.vue) that accepts a color prop from the parent component which is used in determining the class for the text in this component. This is an example of passing data through all the components.

But with Vue 3, we can do this in a cleaner and short way using the new Provide and inject pair. As the name implies, we use provide as either a function or an object to make data available from a parent component to any of its nested component regardless of how deeply nested such a component is. We make use of the object form when passing hard-coded values to provide like this;

# parentComponent.vue

<template>

<div class="home">

<img alt="Vue logo" src="../assets/logo.png" />

<HelloWorld msg="Vue 3 is liveeeee!" :color="color" />

<select name="color" id="color" v-model="color">

<option value="" disabled selected> Select a color</option>

<option :value="color" v-for="(color, index) in colors" :key="index">{{

color

}}</option></select

>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import HelloWorld from "@/components/HelloWorld.vue";

export default {

name: "Home",

components: {

HelloWorld,

},

data() {

return {

colors: ["red", "blue", "green"],

};

},

provide: {

color: 'blue'

}

};

</script>

But for instances where you need to pass a component instance property to provide, we use the function mode so this is possible;

# parentComponent.vue

<template>

<div class="home">

<img alt="Vue logo" src="../assets/logo.png" />

<HelloWorld msg="Vue 3 is liveeeee!" />

<select name="color" id="color" v-model="selectedColor">

<option value="" disabled selected> Select a color</option>

<option :value="color" v-for="(color, index) in colors" :key="index">{{

color

}}</option></select

>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import HelloWorld from "@/components/HelloWorld.vue";

export default {

name: "Home",

components: {

HelloWorld,

},

data() {

return {

selectedColor: "blue",

colors: ["red", "blue", "green"],

};

},

provide() {

return {

color: this.selectedColor,

};

},

};

</script>

Since we don’t need the color props in both the childComponent.vue and colorComponent.vue, we’re getting rid of it. The good thing about using provide is that the parent component does not need to know which component needs the property it is providing.

To make use of this in the component that needs it in this case, colorComponent.vue we do this;

# colorComponent.vue

<template>

<p :class="[color]">This is an example of deeply nested props!</p>

</template>

<script>

export default {

inject: ["color"],

};

</script>

<style>

.blue {

color: blue;

}

.red {

color: red;

}

.green {

color: green;

}

</style>

Here, we use inject which takes in an array of the required variables the component needs. In this case, we only need the color property so we only pass that. After that, we can use the color the same way we use it when using props.

We might notice that if we try to select a new color using the dropdown, the color does not update in colorComponent.vue and this is because by default the properties in provide are not reactive. To Fix that, we make use of computed method.

# parentComponent.vue

<template>

<div class="home">

<img alt="Vue logo" src="../assets/logo.png" />

<HelloWorld msg="Vue 3 is liveeeee!" />

<select name="color" id="color" v-model="selectedColor">

<option value="" disabled selected> Select a color</option>

<option :value="color" v-for="(color, index) in colors" :key="index">{{

color

}}</option></select

>

</div>

</template>

<script>

import HelloWorld from "@/components/HelloWorld.vue";

import { computed } from "vue";

export default {

name: "Home",

components: {

HelloWorld,

},

data() {

return {

selectedColor: "",

todos: ["Feed a cat", "Buy tickets"],

colors: ["red", "blue", "green"],

};

},

provide() {

return {

color: computed(() => this.selectedColor),

};

},

};

</script>

Here, we import computed and pass our selectedColor so that it can be reactive and update as the user selects a different color. When you pass a variable to the computed method it returns an object which has a value. This property holds the value of your variable so for this example, we would have to update colorComponent.vue to look like this;

# colorComponent.vue

<template>

<p :class="[color.value]">This is an example of deeply nested props!</p>

</template>

<script>

export default {

inject: ["color"],

};

</script>

<style>

.blue {

color: blue;

}

.red {

color: red;

}

.green {

color: green;

}

</style>

Here, we change color to color.value to represent the change after making color reactive using the computed method. At this point, the class of the text in this component would always change whenever selectedColor changes in the parent component.

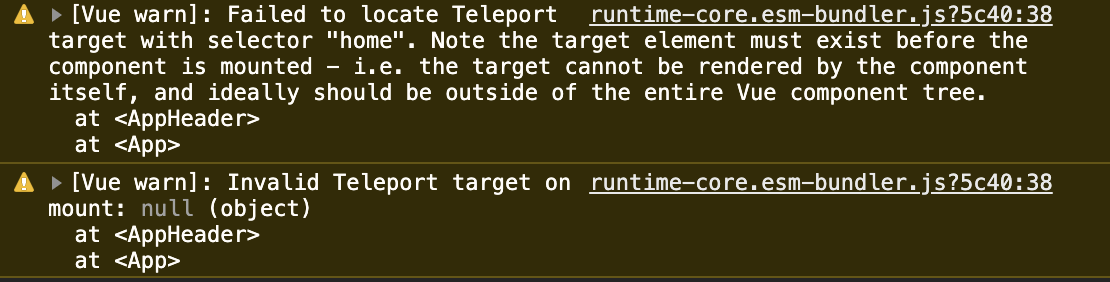

Teleport

There are instances where we create components and place them in one part of our application because of the logic the app uses but are intended to be displayed in another part of our application. A common example of this would be a modal or a popup that is meant to display and cover the whole screen. While we can create a workaround for this using CSS’s position property on such elements, with Vue 3, we can also do using using Teleport.

Teleport allows us to take a component out of its original position in a document, from the default #app container Vue apps are wrapped in and move it to any existing element on the page it’s being used. A good example would be using Teleport to move an header component from inside the #app div to an header It is important to note that you can only Teleport to elements that are existing outside of the Vue DOM.

The Teleport component accepts two props that determine the behavior of this component and they are;

to

This prop accepts either a class name, an id, an element or a data-* attribute. We can also make this value dynamic by passing a:toprop as opposed totoand change the Teleport element dynamically.:disabled

This prop accepts aBooleanand can be used to toggle the Teleport feature on an element or component. This can be useful for dynamically changing the position of an element.

An ideal example of using Teleport looks like this;

# index.html**

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width,initial-scale=1.0" />

<link rel="icon" href="<%= BASE_URL %>favicon.ico" />

<title>

<%= htmlWebpackPlugin.options.title %>

</title>

</head>

<!-- add container to teleport to -->

<header class="header"></header>

<body>

<noscript>

<strong

>We're sorry but <%= htmlWebpackPlugin.options.title %> doesn't work

properly without JavaScript enabled. Please enable it to

continue.</strong

>

</noscript>

<div id="app"></div>

<!-- built files will be auto injected -->

</body>

</html>

In the default index.html file in your Vue app, we add an header element because we want to Teleport our header component to that point in our app. We also added a class to this element for styling and for easy referencing in our Teleport component.

# Header.vue**

<template>

<teleport to="header">

<h1 class="logo">Vue 3 🥳</h1>

<nav>

<router-link to="/">Home</router-link>

</nav>

</teleport>

</template>

<script>

export default {

name: "app-header",

};

</script>

<style>

.header {

display: flex;

align-items: center;

justify-content: center;

}

.logo {

margin-right: 20px;

}

</style>

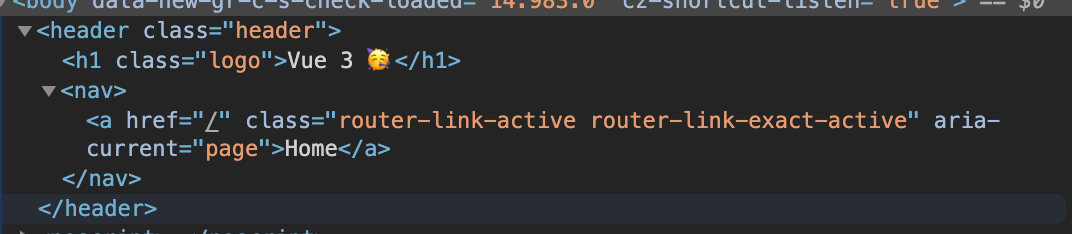

Here, we create the header component and add a logo with a link to the homepage on our app. We also add the Teleport component and give the to prop a value of header because we want this component to render inside this element. Finally, we import this component into our app;

# App.vue

<template>

<router-view />

<app-header></app-header>

</template>

<script>

import appHeader from "@/components/Header.vue";

export default {

components: {

appHeader,

},

};

</script>

In this file, we import the header component and place it in the template so it can be visible in our app.

Now if we inspect the element of our app, we would notice that our header component is inside the headerelement;

Fragments

With Vue 2.x, it was impossible to have multiple root elements in the template of your file and as a workaround, developers started wrapping all elements in a parent element. While this doesn’t look like a serious issue, there are instances where developers want to render a component without a container wrapping around such elements but have to make do with that.

With Vue 3, a new feature called Fragments was introduced and this feature allows developers to have multiple elements in their root template file. So with Vue 2.x, this is how an input field container component would look like;

# inputComponent.vue

<template>

<div>

<label :for="label">label</label>

<input :type="type" :id="label" :name="label" />

</div>

</template>

<script>

export default {

name: "inputField",

props: {

label: {

type: String,

required: true,

},

type: {

type: String,

required: true,

},

},

};

</script>

<style></style>

Here, we have a simple form element component that accepts two props, label and type, and the template section of this component is wrapped in a div. This is not necessarily an issue but if you want the label and input field to be directly inside your form element. With Vue 3, developers can easily rewrite this component to look like this;

# inputComponent.vue

<template class="testingss">

<label :for="label">{{ label }}</label>

<input :type="type" :id="label" :name="label" />

</template>

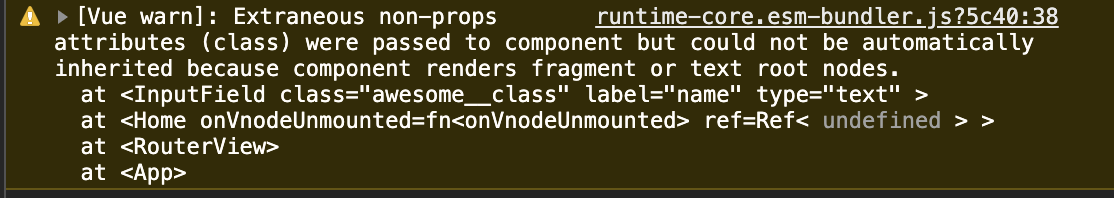

With a single root node, attributes are always attributed to the root node and they are also known as Non-Prop Attributes. They are events or attributes passed to a component that do not have corresponding properties defined in props or emits. Examples of such attributes are class and id. It is, however, required to explicitly define which of the elements in a multi-root node component should be attributed to.

Here’s what this means using the inputComponent.vue from above;

- When adding

classto this component in the parent component, it must be specified which component would thisclassbe attributed to otherwise the attribute has no effect.

<template>

<div class="home">

<div>

<input-component

class="awesome__class"

label="name"

type="text"

></input-component>

</div>

</div>

</template>

<style>

.awesome__class {

border: 1px solid red;

}

</style>

When you do something like this without defining where the attributes should be attributed to, you get this warning in your console;

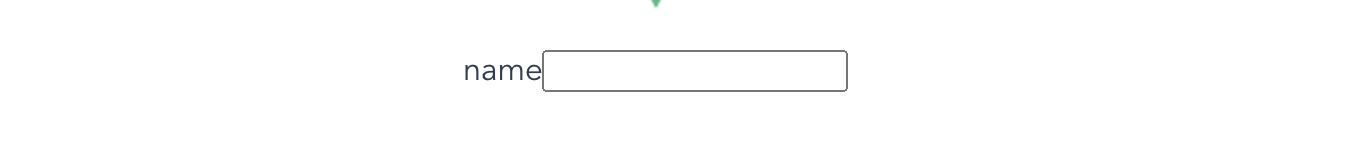

And the border has no effect on the component;

- To fix this, add a

v-bind="$attrs"on the element you want such attributes to be distributed to;

<template>

<label :for="label" v-bind="$attrs">{{ label }}</label>

<input :type="type" :id="label" :name="label" />

</template>

Here, we’re telling Vue that we want the attributes to be distributed to the label element which means we want the awesome__class to be applied to it. Now, if we inspect our element in the browser we would see that the class has now been added to label and hence a border is now around the label.

Global API

It was not uncommon to see Vue.component or Vue.use in main.js file of a Vue application. These types of methods are known are Global APIs and there are quite a number of them in Vue 2.x. One of the challenges of this method is that it makes it impossible to isolate certain functionalities to one instance of your app (if you have more than one instance in your app) without it affecting other apps because they are all mounted on Vue. This is what I mean;

Vue.directive('focus', {

inserted: el => el.focus()

})

Vue.mixin({

/* ... */

})

const app1 = new Vue({ el: '#app-1' })

const app2 = new Vue({ el: '#app-2' })

For the above code, it is impossible to state that the Vue Directive be associated with app1 and the Mixin with app2 but instead, they’re both available in the two apps.

Vue 3 comes with a new Global API in an attempt to fix this type of problem with the introduction of createApp. This method returns a new instance of a Vue app. An app instance exposes a subset of the current global APIs. With this, all APIs (component, mixin, directive, use, etc) that mutate Vue from Vue 2.x are now going to be moved to individual app instances and now, each instance of your Vue app can have functionalities that are unique to them without affecting other existing apps.

Now, the above code can be rewritten as;

const app1 = createApp({})

const app2 = createApp({})

app1.directive('focus', {

inserted: el => el.focus()

})

app2.mixin({

/* ... */

})

It is however possible to create functionalities that you want to be share among all your apps and this can be done by using a factory function.

Events API

One of the most common ways developers adopted for passing data among components that don’t have a parent to child relationship other than using the Vuex Store is the use of Event Bus. One of the reasons why this method is common is because of how easy it is to get started with it;

# eventBus.js

const eventBus = new Vue()

export default eventBus;

After this, the next thing would be to import this file into main.js to make it globally available in our app or to import it in files that you need it;

# main.js

import eventBus from 'eventBus'

Vue.prototype.$eventBus = eventBus

Now, you can emit events and listen for emitted events like this;

this.$eventBus.$on('say-hello', alertMe)

this.$eventBus.$emit('pass-message', 'Event Bus says Hi')

There is a lot of Vue codebase that is filled with code like this. However, with Vue 3, it would be impossible to do because $on, $off, and $once have all been removed but $emit is still available because it is required for children component to emit events to their parent components. An alternative to this would be using provide / inject or any of the recommended third-party libraries.

Conclusion

In this article, we have covered how you can pass data around from a parent component down to a deeply nested child component using the provide / inject pair. We have also looked at how we can reposition and transfer components from one point in our app to another. Another thing we looked at is the multi-root node component and how to ensure we distribute attributes so they work properly. Finally, we also covered the changes to the Events API and Global API.

Further Resources

- “JavaScript Factory Functions with ES6+,” Eric Elliott, Medium

- “Using Event Bus to Share Props Between Vue Components,” Kingsley Silas, CSS-Tricks

- Using Multiple Teleports On The Same Target, Vue.js Docs

- Non-Prop Attributes, Vue.js Docs

- Working With Reactivity, Vue.js Docs

teleport, Vue.js Docs- Fragments, Vue.js Docs

- 2.x Syntax, Vue.js Docs

What are the best off page activities in 2020?

Hi All, I need some suggestions about off page activities what works better?

it will be great if you guys can guide me.