Readability Algorithms Should Be Tools, Not Targets

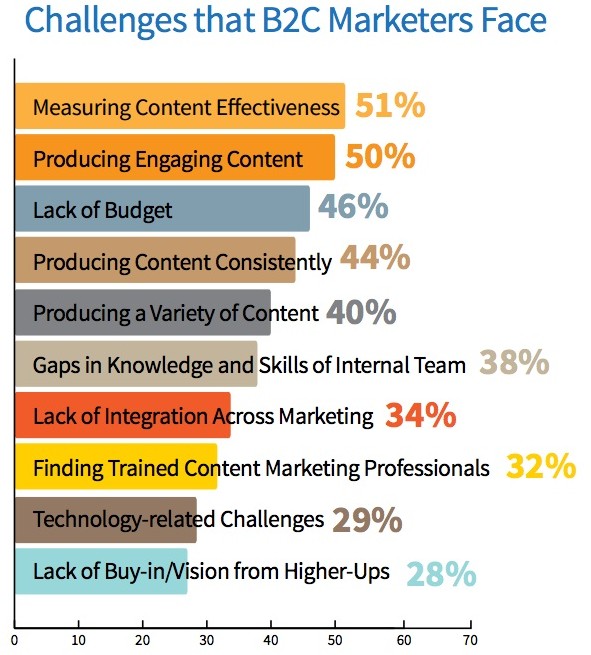

Frederick O’BrienThe web is awash with words. They’re everywhere. On websites, in emails, advertisements, tweets, pop-ups, you name it. More people are publishing more copy than at any point in history. That means a lot of information, and a lot of competition.

In recent years a slew of ‘readability’ programs have appeared to help us tidy up the things we write. (Grammarly, Readable, and Yoast are just a handful that come to mind.) Used everywhere from newsrooms to browser plugins, these systems offer automated feedback on how writing can be clearer, neater, and less contrived. Sounds good right? Well, up to a point.

The concept of ‘readability’ is nothing new. For decades researchers have analyzed factors like sentence length, syllable count, and word complexity in order to ‘measure’ language. Indeed, many of today’s programs incorporate decades-old formulas into their scoring systems.

The Flesch-Kincaid system, for example, is a widely used measure. Created by Rudolf Flesch in 1975, it assigns writing a US grade level. The Gunning fog index serves a similar purpose, and there are plenty more where they came from. We sure do love converting things into metrics.

It’s no mystery why formulas like this are (quite rightly) popular. They help keep language simple. They catch silly mistakes, correct poor grammar, and do a serviceable job of ‘proofreading’ in a pinch. Using them isn’t a problem; unquestioning devotion to their scores, however, is.

No A-Coding For Bad Taste

I want to tread carefully here because I have a lot of time for readability algorithms and the qualities they tend to support — clarity, accessibility, and open communication. I use them myself. They should be used, just not unquestioningly. A good algorithm is a useful tool in the writer’s proverbial toolbox, but it’s not a magic wand. Relying on one too heavily can lead to clunkier writing, short-sightedness, and, worst of all, a total uniformity of online voices.

One of the beauties of the internet is how it melts national borders, creating a fluid space for different cultures and voices to interact in. Readability historically targets academic and professional writing. The Flesch-Kincaid test was originally developed for US Navy technical manuals, for example. Most developers can appreciate the value of clear documentation, but it’s worth remembering that in the world of writing not everything should sound like US Navy technical manuals. There are nuances to different topics, languages, and cultures that monosyllabic American English can’t always capture.

Deference to these algorithms can take writers to absurd lengths. Plain English is one thing, but unquestioning obedience is another. I’ve seen a good few sentences butchered into strings of words that tick readability boxes like ‘write in short sentences’ and ‘use monosyllabic words wherever possible’, but border on nonsensical to the human eye. It’s a near-impossible thing to quantify, but it has been a recurring phenomenon in my own work, and having spoken with other copywriters and journalists I know it’s not just my rampant paranoia at work.

Let’s look at the limitations of these tools. When faced with some of the greatest writers of all time — authors, journalists, copywriters, speech writers — what’s the verdict? How do the masters manage?

- A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens.

The opening chapter receives a grade of E from Readable. - George Orwell’s essay ‘Politics and the English Language’, which bemoans how unclear language hides truth rather than expresses it. He gets a grade of D. Talk about having egg on your face!

- The beginning of The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway does tolerably well in the Hemingway Editor, though you’d have to edit a lot of it down to appease it completely.

A personal favorite that came up here was Ernie Pyle, one of the great war correspondents. His daily columns from the front lines during World War II were published in hundreds of newspapers nationwide. One column, ‘The Death of Captain Waskow’, is widely regarded as a high watermark of war reporting. It receives a grade of B from Readable, which notes the writing is a tad ‘impersonal.’ Have a read and decide for yourself.

Not all copywriting is literary of course, but enjoyable writing doesn’t always have to please readability algorithms. Shoehorning full stops into the middle of perfectly good sentences doesn’t make you Ernest Hemingway. I’m an expert in not being as good as Ernest Hemingway, so you can trust me on that.

Putting Readability Into Context

None of this is supposed to be a ‘gotcha’ for readability algorithms. They provide a quick, easy way to identify long or complex sentences. Sometimes those sentences need editing down and sometimes they’re just fine the way they are. That’s at the author’s discretion, but algorithms speed up the process.

Alternatively, if you’re trying to cut down on fluffy adverbs like ‘very’ you can do a lot worse than turning to the cold, hard feedback of a computer. Readability programs catch plenty of things we might miss, and there are plenty of examples of great writing that would receive suitably great scores when put through the systems listed above. They are useful tools; they’re just not infallible.

Algorithms can only understand topics within the confines of their system. They know what the rules are and how to follow them. Intuition, personal experience, and a healthy desire to break the rules remain human specialties. You can’t program those, not yet anyway. Things aren’t the done thing until they are, after all.

It’s a fine line between thinking your writing has to be clear, and thinking your readers are stupid. You stop seeing the woods for the trees. Every time I hear that the ‘ideal’ article length is X words regardless of the topic or audience, or that certain words should always be used because they improve CTR by 0.06%, I want to gauge my eyes out. Readability algorithms can make sloppy writing competent, but they can’t make good writing great.

Remember, when all is said and done, copy is written for people. From an SEO perspective, Google itself has made it clear in the past that readability should match your target audience. If you’re targeting a mass audience that needs information in layman’s terms, great, do that. If you produce specialized content for experts in a certain field then being more specialized is perfectly appropriate.

As Readable has itself explored, readability can be a kind of public good. Easy to read newspapers spread information better than obtuse ones do. Textbooks written for specific age groups teach better than highly technical ones do. In other words, understand the context you are writing in. Just remember:

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

— Goodhart’s Law

Find Your Voice

I have no beef with readability algorithms. My problem is with the laziness they can enable, the thoughtlessness. Rushing out a draft and running it through a readability tool is not going to improve your writing. As with any skill worth developing you have to be willing to put the hours in. That means going a step or two beyond blindly appeasing algorithms.

Not everyone has a luxury of a great editor, but when you work with one, make full use of the opportunity. Pay attention to their suggestions, ask yourself why they made them. Ask questions, identify recurring problems in your writing and work to address them.

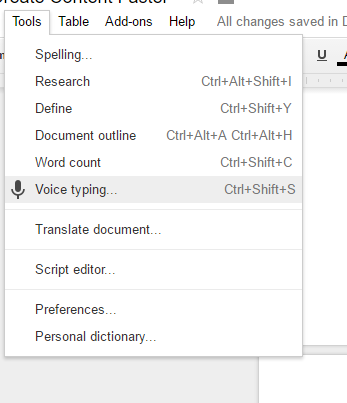

Analyse how the algorithms themselves work. If you’re going to use readability systems they should be supplemental to a genuine search for your own voice. Know how the things calculate scores, what formulas they’re drawing from. Learn the rules yourself. By doing so you earn the knowledge required to break them.

In his aforementioned essay George Orwell offers up his own approach to rules:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

These are founded on solid principles applicable to the web. Where did those principles come from? Not computers, that’s for sure.

Real editors and honest self-reflection do a lot more for your writing ability long term than obeying algorithms does. It all feeds back into your communication, which is an essential skill whether you’re a copywriter, a developer, or a manager. Empathy for other people’s work improves your own.

There is another essential thing good writers do: they read. No algorithm can paper over the cracks of an unengaged mind. Whatever your interests are I guarantee there are people out there writing about it beautifully. Find them and read their work, and find the bad writing too. That can be just as educational.

If you’re so inclined, you may even decide to get all meta about it and read about writing. If you’re not sure where to start, here are a handful of suggestions to get the ball rolling:

- “The Elements of Style,” by William Strunk Jr.

- “On Writing Well,” by William Zinsser

- “Technical Writing with Rachel Andrew,” ShopTalk podcast

- “Politics and the English Language,” by George Orwell

- “Waterhouse on Newspaper Style,” by Keith Waterhouse

- “How to write with style,” by Kurt Vonnegut

- “How to Write Plain English,” by Rudolf Flesch

- “50 Free Resources That Will Improve Your Writing Skills,” by Vitaly Friedman

- Google Developers’ technical writing course for engineering students.

Also keep in mind that readability is not just a question of words. Design is also essential. Layout, visuals, and typography can have just as much impact on readability as the text itself. Think about how copy relates to the content around it or the device it’s being read on. Study advertising and newspapers and branding. On the other side of that sprawling jungle is your voice, and that’s the most valuable thing of all.

To reiterate one last time, readability algorithms are handy tools and I wholeheartedly support using them. However, if you’re serious about making your copy ‘compelling’, ‘informative’, or even (shudder) ‘convert’, then you’re going to have to do a lot more besides. The best writers are those algorithms are trying to imitate, not the other way around.

Whoever you are and whatever your discipline, your writing deserves attention. Whether it’s website copy, technical guides, or marketing material, developing your voice is the best way to communicate the things most important to you. By all means, use the tools at your disposal, but just don’t phone it in.

(ra, yk, il)

(ra, yk, il)