Our dear friend Robin has a new essay called In Praise of Shadows. Now, before you hop over there looking for nuggets on CSS box shadows, text shadows, and shadow filters… this is not that. It’s an essay on photography and what Robin has learned about handing shadows with a camera.

So, why share this? Because it’s cool as heck that he made an article directed page dedicated to one essay. And you’ll learn a lot about CSS if you crack open DevTools on it:

- Centering techniques. Notice how CSS Grid is used on the

<body>simply to center the pamphlet. Then Robin reaches for it again on each.frameof the essay to do the same thing with the content. - “Faux” background images. Robin could have made a lot of work for himself by creating a CSS class for each

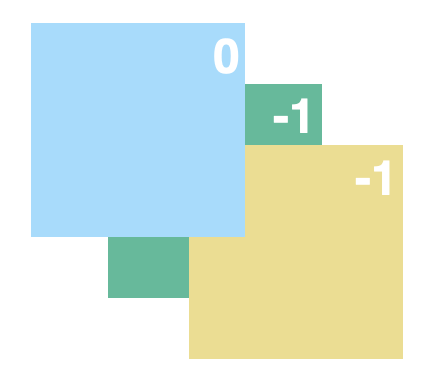

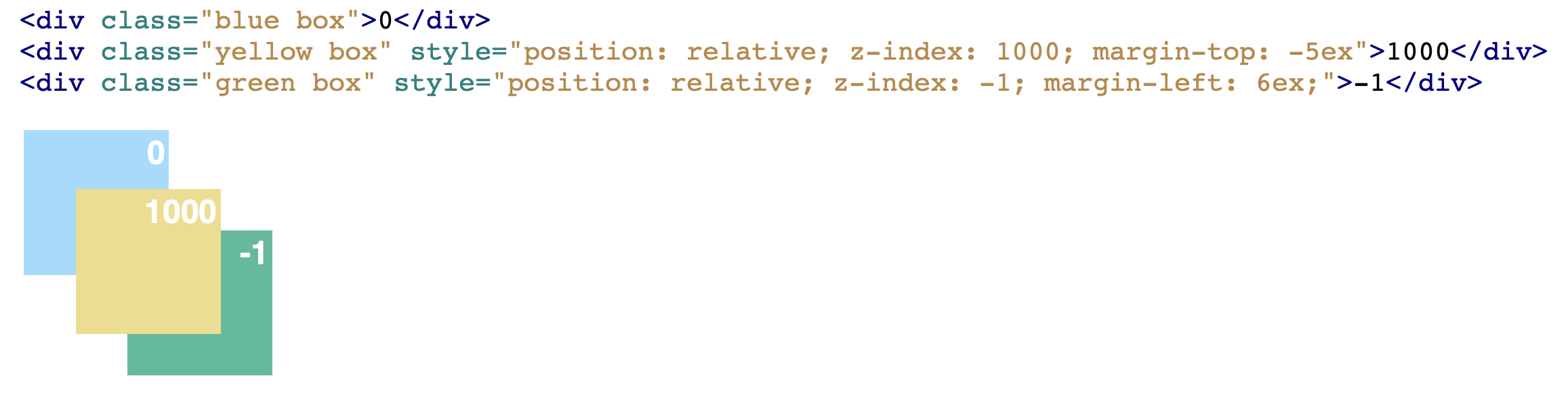

.frameto get the background images. Instead, he usesobject-fit: coveron inlined HTML<img>s to maintain the aspect ratio while filling the.framecontainer. (He’s actually written about this before.) That sure saves a lot of CSS’ing, but it also allows him to use alt text if needed. I sorta wonder if a<figure>/<figcaption>structure could’ve worked here instead but I doubt it would provide much additional benefit for what’s going on. - Stacking contexts. Another perk of those faux background images? They use absolute positioning which creates a stacking context, allowing Robin to set a

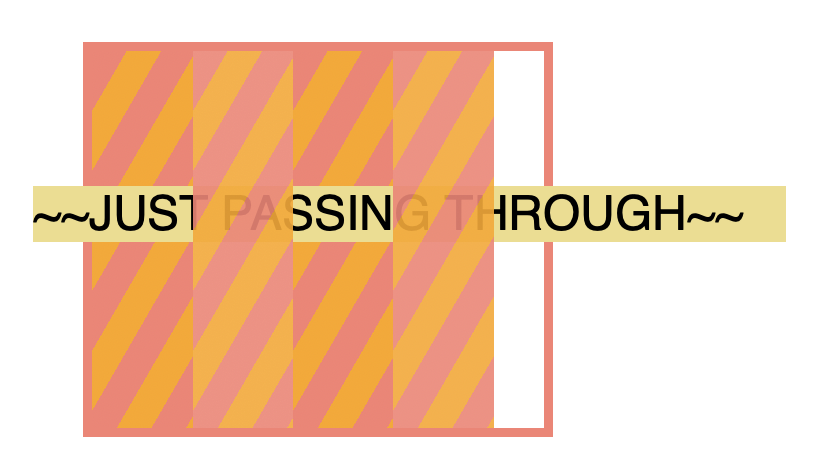

z-index: 0on the images. That way, the text stacks directly on top withz-index: 1. Again, CSS Grid is handling all the centering so things are nicely aligned. - Scroll snapping. I always love it when I see CSS scroll snapping in the wild. Robin made a nice choice to use it here, as it really lends to the whole page-turning experience while scrolling through frames. Horizontal scrolling can be maddening, but also extremely elegant when executed well as it is here in how it enhances the narrow-column design. If you want a nice explanation of how it all works, Robin has also written about horizontal scroll snapping.

If nothing else, Robin is an excellent writer and it’s worth reading anything he publishes, CSS and beyond.

To Shared Link — Permalink on CSS-Tricks

In Praise of Shadows originally published on CSS-Tricks. You should get the newsletter.