This article is part of our “Advanced Git” series. Be sure to follow us on Twitter or sign up for our newsletter to hear about the next articles!

In this third installment of our “Advanced Git” series, we’ll look at pull requests — a great feature which helps both small and larger teams of developers. Pull requests not only improve the review and the feedback process, but they also help tracking and discussing code changes. Last, but not least, pull requests are the ideal way to contribute to other repositories you don’t have write access to.

Advanced Git series:

- Part 1: Creating the Perfect Commit in Git

- Part 2: Branching Strategies in Git

- Part 3: Better Collaboration With Pull Requests

You are here! - Part 4: Merge Conflicts

Coming soon! - Part 5: Rebase vs. Merge

- Part 6: Interactive Rebase

- Part 7: Cherry-Picking Commits in Git

- Part 8: Using the Reflog to Restore Lost Commits

What are pull requests?

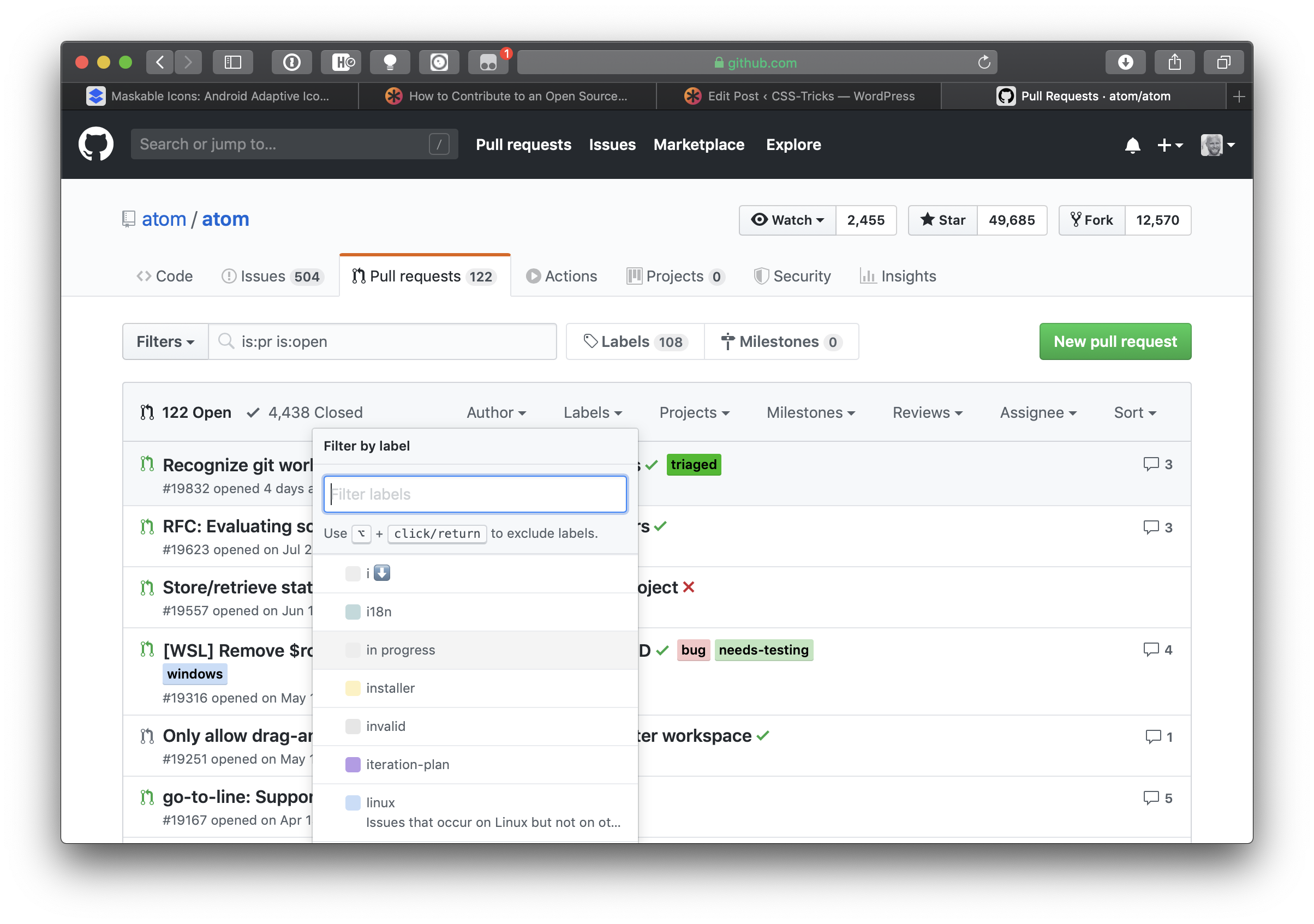

First of all, it’s important to understand that pull requests are not a core Git feature. Instead, they are provided by the Git hosting platform you’re using: GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket, AzureDevops and others all have such a functionality built into their platforms.

Why should I create a pull request?

Before we get into the details of how to create the perfect pull request, let’s talk about why you would want to use this feature at all.

Imagine you’ve just finished a new feature for your software. Maybe you’ve been working in a feature branch, so your next step would be merging it into the mainline branch (master or main). This is totally fine in some cases, for example, if you’re the only developer on the project or if you’re experienced enough and know for certain your team members will be happy about it.

By the way: If you want to know more about branches and typical branching workflows, have a look at our second article in our “Advanced Git” series: “Branching Strategies in Git.”

However, what if your changes are a bit more complex and you’d like someone else to look at your work? This is what pull requests were made for. With pull requests you can invite other people to review your work and give you feedback.

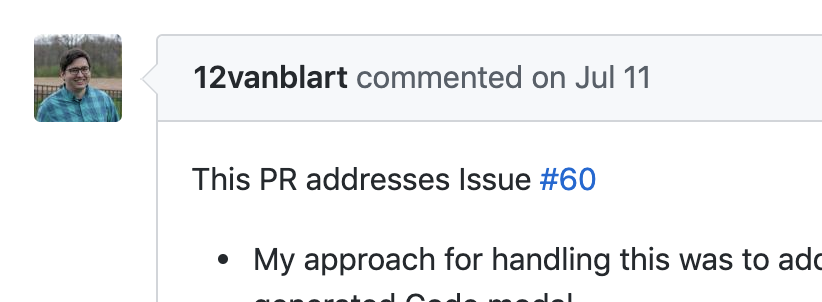

Once a pull request is open, you can discuss your code with other developers. Most Git hosting platforms allow other users to add comments and suggest changes during that process. After your reviewers have approved your work, it might be merged into another branch.

Having a reviewing workflow is not the only reason for pull requests, though. They come in handy if you want to contribute to other repositories you don’t have write access to. Think of all the open source projects out there: if you have an idea for a new feature, or if you want to submit a patch, pull requests are a great way to present your ideas without having to join the project and become a main contributor.

This brings us to a topic that’s tightly connected to pull requests: forks.

Working with forks

A fork is your personal copy of an existing Git repository. Going back to our Open Source example: your first step is to create a fork of the original repository. After that, you can change code in your own, personal copy.

After you’re done, you open a pull request to ask the owners of the original repository to include your changes. The owner or one of the other main contributors can review your code and then decide to include it (or not).

Important Note: Pull requests are always based on branches and not on individual commits! When you create a pull request, you base it on a certain branch and request that it gets included.

Making a reviewer’s life easier: How to create a great pull request

As mentioned earlier, pull requests are not a core Git feature. Instead, every Git platform has its own design and its own idea about how a pull request should work. They look different on GitLab, GitHub, Bitbucket, etc. Every platform has a slightly different workflow for tracking, discussing, and reviewing changes.

Desktop GUIs like the Tower Git client, for example, can make this easier: they provide a consistent user interface, no matter what code hosting service you’re using.

Having said that, the general workflow is always the same and includes the following steps:

- If you don’t have write access to the repository in question, the first step is to create a fork, i.e. your personal version of the repository.

- Create a new local branch in your forked repository. (Reminder: pull requests are based on branches, not on commits!)

- Make some changes in your local branch and commit them.

- Push the changes to your own remote repository.

- Create a pull request with your changes and start the discussion with others.

Let’s look at the pull request itself and how to create one which makes another developer’s life easier. First of all, it should be short so it can be reviewed quickly. It’s harder to understand code when looking at 3,000 lines instead of 30 lines.

Also, make sure to add a good and self-explanatory title and a meaningful description. Try to describe what you changed, why you opened the pull request, and how your changes affect the project. Most platforms allow you to add a screenshot which can help to demonstrate the changes.

Approve, merge, or decline?

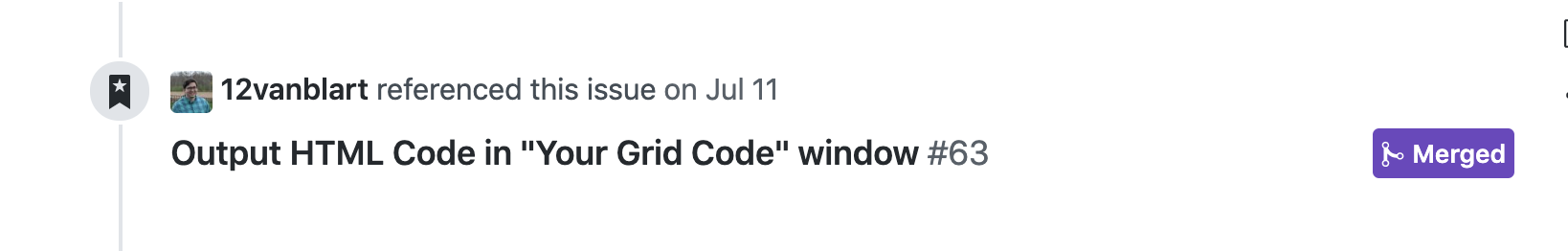

Once your changes have been approved, you (or someone with write access) can merge the forked branch into the main branch. But what if the reviewer doesn’t want to merge the pull request in its current state? Well, you can always add new commits, and after pushing that branch, the existing pull request is updated.

Alternatively, the owner or someone else with write access can decline the pull request when they don’t want to merge the changes.

Safety net for developers

As you can see, pull requests are a great way to communicate and collaborate with your fellow developers. By asking others to review your work, you make sure that only high-quality code enters your codebase.

If you want to dive deeper into advanced Git tools, feel free to check out my (free!) “Advanced Git Kit”: it’s a collection of short videos about topics like branching strategies, Interactive Rebase, Reflog, Submodules and much more.

Advanced Git series:

- Part 1: Creating the Perfect Commit in Git

- Part 2: Branching Strategies in Git

- Part 3: Better Collaboration With Pull Requests

You are here! - Part 4: Merge Conflicts

Coming soon! - Part 5: Rebase vs. Merge

- Part 6: Interactive Rebase

- Part 7: Cherry-Picking Commits in Git

- Part 8: Using the Reflog to Restore Lost Commits

The post Better Collaboration With Pull Requests appeared first on CSS-Tricks. You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.