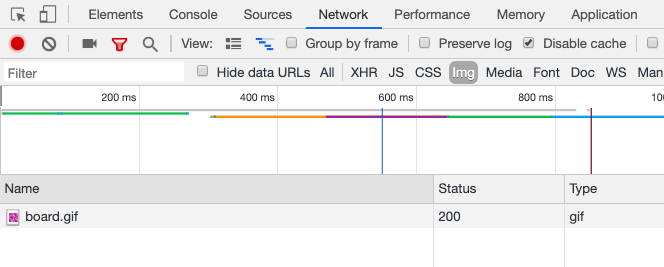

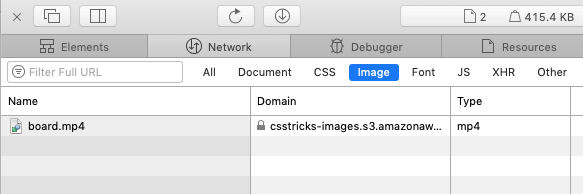

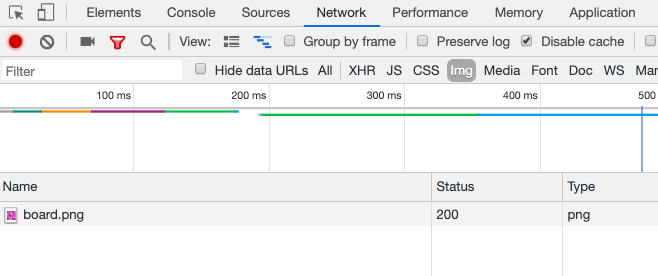

So you want an auto-playing looping video without sound? In popular vernacular this is the very meaning of the word GIF. The word has stuck around but the image format itself is ancient and obsolete. Twitter, for example, has a “GIF” button that actually inserts a <video> element with an MP4 file into your tweet — no .gif in sight. There are a beguiling amount of ways to achieve the same outcome but one thing is clear: there’s really no good reason to use the bulky .gif file format anymore.

Use a HTML <video> element

It’s easy to recreate the behavior of a GIF using the HTML video element.

<video autoplay loop muted playsinline src="cats.mp4"></video>With this code the video will play automatically in a continuous loop with no audio. playsinline means that mobile browsers will play the video where it is on the page rather than opening in fullscreen.

While the HTML video element itself has been supported for many years, the same can’t be said for the wide variety of video formats.

Videos are made up of two parts: the container and the video codec. (If your video contains audio then it is made up of three parts, the third being the audio codec.) Containers can store video, audio, subtitles and meta information. The two most common containers for video on the web are MP4 and WebM. The container is the same as the file type — if a file ends with a .mp4 extension, that means it’s using an MP4 container. The file extension doesn’t tell you the codec though. Examples of video codecs commonly used on the web include VP8, VP9, H.264 and HEVC (H.265). For your video to play online, the browser needs to support both the video container and the codec.

Browser support for video is a labyrinthine mess, which is part of the reason YouTube embeds are ubiquitous, but that doesn’t work for our use case. Let’s look at the video formats that are worth considering.

Containers

- MP4 was originally released in 2001. It is supported by all web browsers and has been for quite some time.

- WebM was released in 2010. It works in all browsers except for iOS Safari.

Codecs

- The H.264 codec works in all browsers.

- HEVC/H.265, the successor of H.264, is supported by Safari, Edge, and Chrome (as of version 105).

- VP9 is the successor to the VP8 codec. VP9 is supported by all the browsers that support WebM.

- The AV1 codec has been supported in Chrome since 2018 and Firefox since 2019. It has not yet shipped in Edge or Safari.

An MP4 file using the H.264 codec will work everywhere, but it doesn’t deliver the best quality or the smallest file size.

AV1 doesn’t have cross-browser support yet but, released in 2018, it’s the most modern codec around. It’s already being used, at least for some videos and platforms, by Netflix, YouTube and Vimeo. AV1 is a royalty-free video codec designed specifically for the internet. AV1 was created by the Alliance for Open Media (AOM), a group founded by Google, Mozilla, Cisco, Microsoft, Netflix, Amazon, and Intel. Apple is now also a member, so it’s safe to assume all browsers will support AV1 eventually. Edge is “still evaluating options to support AVIF and AV1.”

The recently redesigned website from development consultancy Evil Martians is a testament to the file-size reduction that AV1 is capable of.

If you want to use newer video formats with fallbacks for older browsers, you can use multiple <source> elements. The order of the source elements matter. Specify the ideal source at the top, and the fallback after.

<video autoplay loop muted playsinline>

<source src="cats.webm" type="video/webm"> <!-- ideal -->

<source src="cats.mp4" type="video/mp4"> <!-- fallhack -->

</video>Given the above code, cats.webm will be used unless the browser does not support that format, in which case the MP4 will be displayed instead.

What if you want to include multiple MP4 files, but with each using a different codec? When specifying the type you can include a codecs parameter. The syntax is horrifically complicated for anybody who isn’t some kind of hardcore codec nerd, but it looks something like this:

<video autoplay loop muted playsinline>

<source src="cats.mp4" type="video/mp4; codecs=av01.0.05M.08" >

<source src="cats.mp4" type="video/mp4" >

</video>Using the above code the browser will select AV1 if it can play that format and fallback to the universally-supported H.264 if not. For AV1, the codecs parameter always starts with av01. The next number is either 0 (for main profile), 1 (for high profile) or 2 (for professional profile). Next comes a two-digit level number. This is followed either by the letter M (for main tier) or H (for high tier). It’s difficult to understand what any those things mean, so you could provide your AV1 video in a WebM container and avoid specifying the codec entirely.

Most video editing software does not allow you to export as AV1, or even as WebM. If you want to use one of those formats you’ll need to export your video as something else, like a .mov, and then convert it using the command-line tool FFmpeg:

ffmpeg -i yourSourceFile.mov -map_metadata -1 -c:a libopus -c:v librav1e -qp 80 -tile-columns 2 -tile-rows 2 -pix_fmt yuv420p -movflags +faststart -vf "scale=trunc(iw/2)*2:trunc(ih/2)*2" videoTitle.mp4You should use the most high-resolution source file you can. Obviously, once image quality is lost you can’t improve it through conversion to a superior format. Using a .gif as a source file isn’t ideal because the visual quality of .gif isn’t great, but you’ll still get the benefit of a large reduction in file size:

ffmpeg -i cats.gif -map_metadata -1 -an opus -c:v librav1e -qp 80 -tile-columns 2 -tile-rows 2 -pix_fmt yuv420p -movflags +faststart -vf "scale=trunc(iw/2)*2:trunc(ih/2)*2" cats.mp4On Mac, you can download FFmpeg using Homebrew:

brew install ffmpegHere’s a nice example of video in web design on the masterfully designed Oxide website:

If you want to use the video as a background and place other elements on top of it, working with <video> is slightly more challenging than a CSS background-image, and requires code that goes something like this:

.video-parent {

position: relative;

width: 100vw;

height: 100vh;

}

.video-parent video {

object-fit: cover;

position: absolute;

inset: 0;

z-index: -1;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}The <video> element is a perfectly okay option for replacing GIFs but it does have one unfortunate side-effect: it prevents a user’s screen from going to sleep, as explained in this post from an ex- product manager on the Microsoft Edge browser.

The benefits of using an image

Whether it’s an animated WebP or animated AVIF file, using images rather than video comes with some benefits.

I’m not sure how many people actually want to art-direct their GIFs, but using the <picture> element does open up some possibilities that couldn’t easily be achieved with <video>. You could specify different animations for light and dark mode, for example:

<picture>

<source srcset="dark-animation.avifs" media="(prefers-color-scheme: dark)">

<img src="light-animation.avif" alt="">

</picture>We might want a video on mobile to be a different aspect ratio than on desktop. We could just crop parts of the image with CSS, but that seems like a waste of bytes and somewhat haphazard. Using a media query we can display a different animated image file based on the screen size or orientation:

<picture>

<source type="image/avif" srcset="typeloop-landscape.avifs" media="(orientation: landscape)"">

<img src="typeloop-portrait.avif" alt="">

</picture>All of this is possible with video — you can use matchMedia to do any media queries in JavaScript and programmatically change the src of a <video> element:

const mediaQuery = window.matchMedia("(prefers-color-scheme: dark)");

if (mediaQuery.matches) {

document.querySelector("video").src = "dark-animation.mp4";

}I believe that whenever there’s a way to do something with markup it should be preferred over doing it JavaScript.

You can use raster images inside of an SVG using the <image> element. This includes animated image formats. There’s not much you can do with an image inside an SVG that you couldn’t already do with CSS, but if you group an image with vector elements inside an SVG, then you do get the benefit that the different elements move and scale together.

The <img> element has the benefit of native lazy-loading:

<img loading="lazy" src="cats.avif" alt="cats">If you want a background video that takes up the entire screen, it’s slightly easier to position a background-image than a HTML <video> element:

.background-video {

background-image: url("coolbackground.webp");

background-repeat: no-repeat;

background-size: cover;

height: 100vh;

width: 100vh;

} If you want to support older browsers you could use the <picture> element with a fallback of either an animated WebP or, just for Safari, an img with a video src, or if you care about ancient browsers, maybe an APNG (animated PNG) or a GIF. Using multiple image formats this way might be impractical if you’re optimizing images manually; but it is relatively trivial if you’re using a service like Cloudinary.

<picture>

<source type="image/avif" srcset="cats.avif">

<img src="cats.webp">

</picture>There’s still no well-supported way to specify fallback images for CSS backgrounds. image-set is an equivalent of the <picture> element, [but for background-image. Unfortunately, only Firefox currently supports the type attribute of image-set.

.box {

background-image: image-set(

url("cats.avif") type("image/avif"),

url("cats.webp") type("image/webp"));

}This browser support data is from Caniuse, which has more detail. A number indicates that browser supports the feature at that version and up.

Desktop

| Chrome | Firefox | IE | Edge | Safari |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109* | 89 | No | 105* | TP |

Mobile / Tablet

| Android Chrome | Android Firefox | Android | iOS Safari |

|---|---|---|---|

| 105* | 104 | 105* | 16.1 |

Use animated WebP

The WebP image format was introduced by Google in 2010. WebP, including animated WebP, has broad browser support.

<img src="nyancat.webp" alt="A cat flying through space leaving a rainbow trail">This browser support data is from Caniuse, which has more detail. A number indicates that browser supports the feature at that version and up.

Desktop

| Chrome | Firefox | IE | Edge | Safari |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | 65 | No | 18 | 16.0 |

Mobile / Tablet

| Android Chrome | Android Firefox | Android | iOS Safari |

|---|---|---|---|

| 105 | 104 | 4.2-4.3 | 14.0-14.4 |

Use animated AVIF

WebP is now twelve years old. The more modern AV1 Image File Format (AVIF), released in 2019, is the best image format for most use cases on the web. Converting a .gif file to AVIF can reduce bytes by over 90%.

<img src="nyancat.avif" alt="A cat flying through space leaving a rainbow trail">As its name suggests, AVIF is based on the the AV1 video codec. Like WebP, AVIF can be used for both still images and animation. There’s not much difference between an animated AVIF file and an AV1 video in an MP4 container.

You can put a shadow on AVIF animation, e.g.:

filter: drop-shadow(2px 4px 6px black);AVIF is already supported by Safari, Firefox, Samsung Internet, and Chrome. Firefox only shipped support for still images, not animated AVIF. Safari supports animation as of version 16.1. Unfortunately, because Firefox does support AVIF, just not animated AVIF, it’s impossible to successfully use the <picture> element to display AVIF only to browsers that support animation. Given the following code, Firefox would display the AVIF, but as a static image, rather than showing the animated WebP version:

<picture>

<source srcset="https://fonts.gstatic.com/s/e/notoemoji/latest/1f4a9/512.avif" type="image/avif">

<img src="https://fonts.gstatic.com/s/e/notoemoji/latest/1f4a9/512.webp" alt="💩" width="32" height="32">

</picture>Tooling for AVIF is still improving. Video editing software does not enable you to export footage as animated AVIF or animated WebP. You’ll need to export it in some other format and then convert it. On the website ezgif.com you can upload a video file or a .gif and convert it to AVIF or WebP. You could also use FFmpeg. Using Cloudinary you can upload a video file or an old .gif and convert it to pretty much any format you want — including animated WebP and animated AVIF. As of time of writing, Squoosh, an image conversion app, doesn’t support animated AVIF.

Adoption remains lacking in design software. When viewing a prototype, Figma will play any animated GIFs included in the design. For AVIF, by contrast, you can’t even import or export a still image.

Use a video with an <img> element

In 2018, Safari 11.1 gave developers the ability to use a video file as the source of the HTML <img> element. This works in Safari:

<img src="cat.mp4" alt="A Siamese cat walking in a circle">All the same codecs that Safari supports for <video> are supported by <img>. This means you can use MP4, H.264, and HEVC.

In Safari, video files will also work anyplace in CSS where you could use an image, like background-image or border-image:

.video-border {

border: 40px solid transparent;

border-image: url(abstract_bg_animation.mp4) 100 round;

}One strange consequence of this feature in Safari is that the poster image of a <video> element can also be a video. The poster will autoplay even if you have blocked video’s from auto-playing. Safari claimed this feature came with performance benefits, not just over using .gif files but also over using the <video> element. According to Apple:

By placing your videos in

<img>elements, the content loads faster, uses less battery power, and gets better performance.

Colin Bendell, co-author of O‘Reilly’s High Performance Images, wrote about the shortcomings of the <video> tag for our use case:

Unlike

<img>tags, browsers do not preload<video>content. Generally preloaders only preload JavaScript, CSS, and image resources because they are critical for the page layout. Since<video>content can be any length – from micro-form to long-form –<video>tags are skipped until the main thread is ready to parse its content. This delays the loading of<video>content by many hundreds of milliseconds.[…]

Worse yet, many browsers assume that

<video>tags contain long-form content. Instead of downloading the whole video file at once, which would waste your cell data plan in cases where you do not end up watching the whole video, the browser will first perform a 1-byte request to test if the server supports HTTP Range Requests. Then it will follow with multiple range requests in various chunk sizes to ensure that the video is adequately (but not over-) buffered. The consequence is multiple TCP round trips before the browser can even start to decode the content and significant delays before the user sees anything. On high-latency cellular connections, these round trips can set video loads back by hundreds or thousands of milliseconds.

Chrome has marked this as “WontFix” — meaning they don’t intend to ever support this feature, for various reasons. There is, however, an open issue on GitHub to add it to the HTML spec, which would force Google’s hand.

Respecting user preferences

Video has the benefit of automatically respecting a users preferences. Firefox and Safari allow users to block videos from automatically playing, even if they don’t have any audio. Here are the settings in Firefox, for example:

The user can still decide to watch a certain video by right-clicking and pressing play in the menu, or enable autoplay for all videos on a specific website.

For users who haven’t disabled autoplay, it’s nice to have the option to pause an animation if you happen to find it annoying or distracting (a user can still right-click to bring up the pause option in a menu when video controls aren’t shown). Success Criterion 2.2.2 Pause, Stop, Hide of the WCAG accessibility guidelines states:

For any moving, blinking or scrolling information that (1) starts automatically, (2) lasts more than five seconds, and (3) is presented in parallel with other content, there is a mechanism for the user to pause, stop, or hide it unless the movement, blinking, or scrolling is part of an activity where it is essential.

With the <video> element, you’ll achieve that criterion without any additional development.

There’s also a “reduce motion” user setting that developers can respect by reducing or removing CSS and JavaScript web animations.

You can also use it to display a still image instead of an animation. This takes extra code to implement — and you need to host a still image in additional to your animated image.

<picture>

<source

srcset="nyancat.avifs"

type="image/avif"

media="(prefers-reduced-motion: no-preference)"

/>

<img src="nyancat.png" alt="Nyan cat" width="250" height="250" />

</picture>There’s another downside. When using the <picture> element in this way if the user has checked “reduce motion”there’s no way for them to see the animation. Just because a user prefers less animation, doesn’t mean they never want any — they might still want to be able to opt-in and watch one every now and then. Unlike the <video> element, displaying a still image takes away that choice.

Checking for progressive enhancement

If you want to check that your <picture> code is properly working and fallback images are being displayed, you can use the Rendering tab in Chrome DevTools to turn off support for AVIF and WebP image formats. Seeing as all browsers now support WebP, this is a pretty handy feature.

While it’s usually the best option to create animations with CSS, JavaScript, DOM elements, canvas and SVG, as new image and video formats offer smaller files than what was previously possible, they become a useful option for UI animation (rather than just nyancat loops). For one-off animations, an AVIF file is probably going to be more performant than importing an entire animation library.

Lottie

After Effects is a popular animation tool from Adobe. Using an extension called Bodymovin, you can export animation data from After Effects as a JSON file.

Then there’s Lottie, an open-source animation library from Airbnb that can take that JSON file and render it as an animation on different platforms. The library is available for native iOS, Android, and React Native applications, as well as for the web. You can see examples from Google Home, Target, and Walgreens, among others.

Once you’ve included the dependency you need to write a small amount of JavaScript code to get the animation to run:

<div id="lottie"></div>const animation = bodymovin.loadAnimation({

container: document.getElementById('lottie'),

path: 'myAnimation.json',

renderer: 'svg',

loop: true,

autoplay: true,

})You can optionally change those settings to only play after an event:

const lottieContainer = document.getElementById('lottie');

const animation = bodymovin.loadAnimation({

container: lottieContainer,

path: 'myAnimation.json',

renderer: 'svg',

loop: true,

autoplay: false,

})

// Play the animation on hover

lottieContainer.addEventListener('mouseover', () => {

animation.play();

});

// Stop the animation after playing once

animation.addEventListener('loopComplete', function() {

animation.stop();

});Here’s a cute example of a cat typing on a keyboard I took from Lottiefiles.com (the website is a useful website for previewing your own Lottie JSON file animations, rather than needing to install After Effects, as well finding animations from other creatives):

You can also programmatically play an animation backwards and change the playback rate.

If you do choose to use Lottie, there’s a Figma plugin for Lottie but all it does is convert JSON files to .gif so that they can be previewed in prototyping mode.

Abd what about Lottie’s performance? There’s size of the library — 254.6KB (63.8 gzipped) — and the size of the JSON file to consider. There’s also the amount of DOM elements that get created for the SVG parts. If you run into this issue, Lottie has the option to render to a HTML <canvas>, but you’ll need to use a different version of the JavaScript library.

const animation = bodymovin.loadAnimation({

container: document.getElementById('lottie'),

path: 'myAnimation.json',

renderer: 'canvas',

})Lottie isn’t a full replacement for gifs. While After Effects itself is often used with video clips, and Lottie can render to a HTML <canvas>, and a canvas can play video clips, you wouldn’t use a Lottie file for that purpose. Lottie is for advanced 2D animations, not so much for video. There are other tools for creating complex web animations with a GUI like SVGator and Rive, but I haven’t tried them myself. 🤷♂️

I wish there was a TL;DR for this article. For now, at least, there’s no clear winner…

GIFs Without the .gif: The Most Performant Image and Video Options Right Now originally published on CSS-Tricks, which is part of the DigitalOcean family. You should get the newsletter.