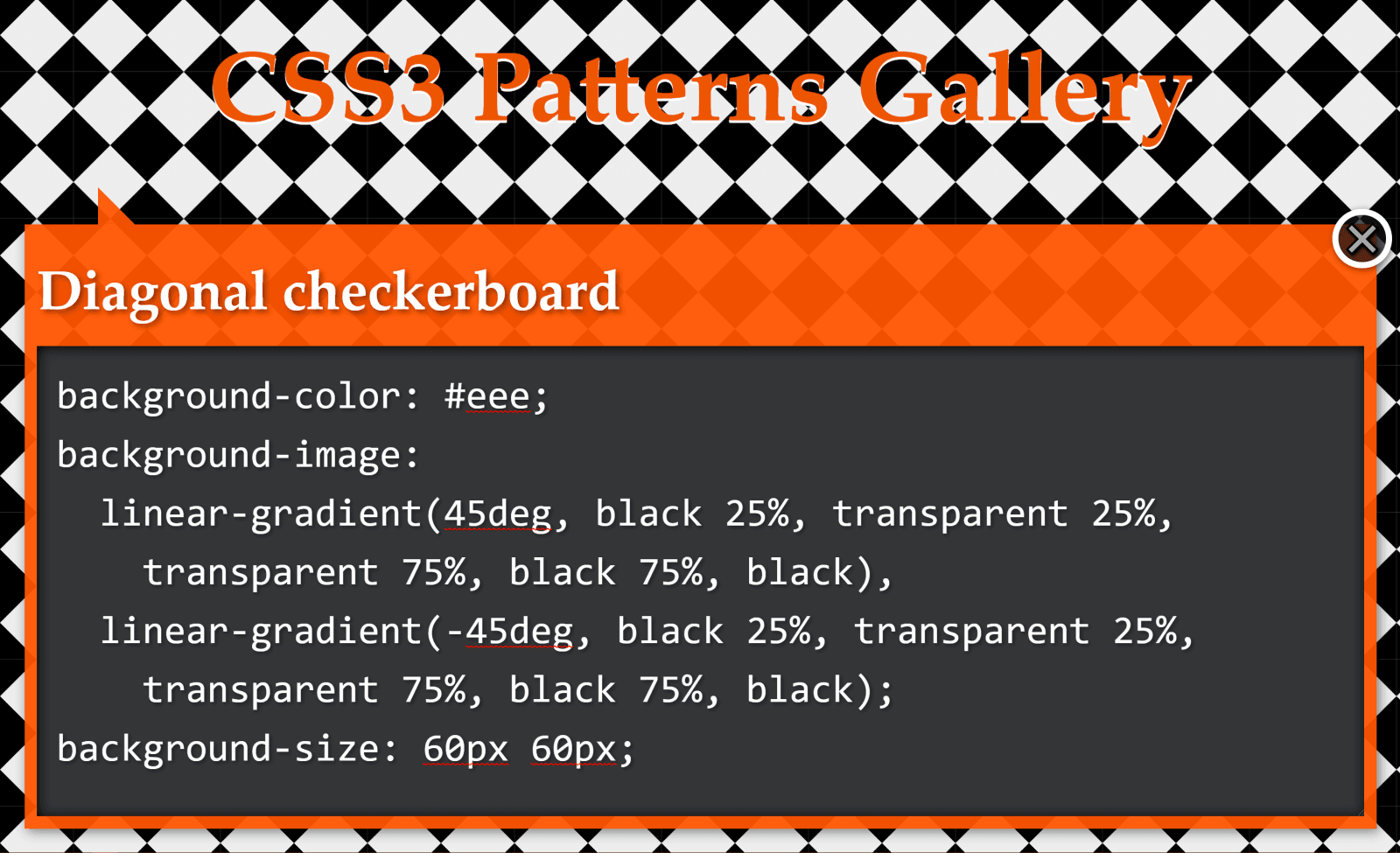

You can create stripes in CSS. That’s all I thought about in terms of CSS background patterns for a long time. There’s nothing wrong with stripes; stripes are cool. They can be customized into wide and narrow bands, criss-crossed into a checked pattern, and played with in other ways using the idea of hard stops. But stripes can be boring, too. Too conventional, out of fashion, and sometimes even unpleasant.

Thankfully, we can conjure up far more background patterns than you can even imagine with CSS, with code that is similar in spirit to stripes.

Background patterns are images repeated across a background. They can be done by referencing an external image, like a PNG file, or can be drawn with CSS, which is traditionally done using CSS gradients.

Linear gradients (and repeating linear gradients) for instance, are typically used for stripes. But there are other ways to create cool background patterns. Let’s see how we can use gradients in other ways and toss in other things, like CSS shapes and emoji, to spice things up.

Gradient patterns

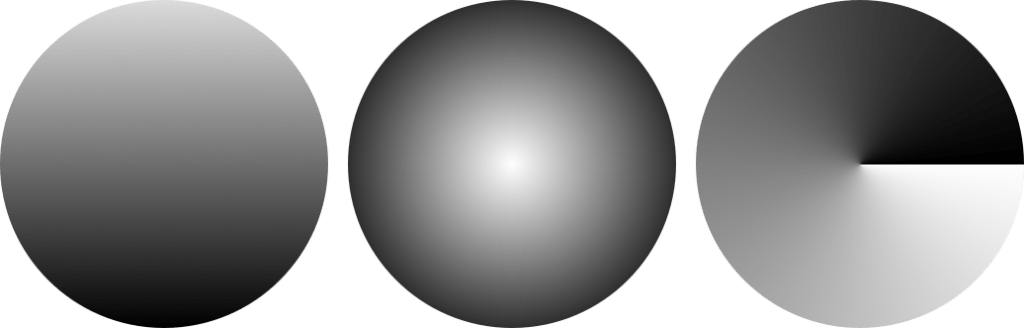

There are three types of CSS gradients.

linear-gradient(): Colors flow from left-to-right, top-to-bottom, or at any angle you choose in a single direction.radial-gradient(): Colors start at a single point and emanate outwardconic-gradient(): Similar in concept to radial gradients, but the color stops are placed around the circle rather than emanating from the center point.

I recommend checking out the syntax for all the gradients to thoroughly understand how to start and end a color in a gradient.

Radial gradient patterns

Let’s look at radial gradients first because they give us very useful things: circles and ellipses. Both can be used for patterns that are very interesting and might unlock some ideas for you!

background: radial-gradient(<gradient values>)Here’s a pattern of repeating watermelons using this technique:

background:

radial-gradient(circle at 25px 9px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(circle at 49px 28px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(circle at 38px 1px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(circle at 20px 4px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(circle at 80px 4px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(circle at 50px 10px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(circle at 60px 16px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(circle at 70px 16px, black 2px, transparent 2px),

radial-gradient(ellipse at 50px 0, red 33px, lime 33px, lime 38px, transparent 38px)

white;

background-size: 100px 50px;We start by providing a background size on the element then stack up the gradients inside it. An ellipse forms the green and red parts. Black circles are scattered across to represent the watermelon seeds.

The first two parameters for a radial gradient function determine whether the gradient shape is a circle or an ellipse and the starting position of the gradient. That’s followed by the gradient color values along with the start and ending positions within the gradient.

Conic gradient patterns

Conic gradients create ray-like shapes. Like linear and radial gradients, conic gradients can be used to create geometric patterns.

background: conic-gradient(<gradient values>)background:

conic-gradient(yellow 40deg, blue 40deg, blue 45deg, transparent 45deg),

conic-gradient(transparent 135deg, blue 135deg, blue 140deg, transparent 140deg) ;

background-size: 60px 60px;

background-color: white;The rub with conic gradient is that it’s not supported in Firefox, at least at the time of writing. It’s always worth keeping an eye out for deeper support.

This browser support data is from Caniuse, which has more detail. A number indicates that browser supports the feature at that version and up.

Desktop

| Chrome | Firefox | IE | Edge | Safari |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 69 | No | No | 79 | 12.1 |

Mobile / Tablet

| Android Chrome | Android Firefox | Android | iOS Safari |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81 | No | 81 | 12.2-12.4 |

Emoji icon patterns

This is where things begin to get interesting. Rather than just using geometric patterns (as in gradients), we now use the organic shapes of emojis to create background patterns. 🎉

It starts with emoji icons.

Solid-color emoji patterns

We can create emoji icons by giving emojis a transparent color and text shadow.

color: transparent;

text-shadow: 0 0 black;Those icons can then be turned into an image that can be used as a background, using SVG.

<svg>

<foreignObject>

<!-- The HTML code with emoji -->

</foreignObject>

</svg>The SVG can then be referred by the background property using data URL.

background: url("data:image/svg+xml,<svg xmlns=%22http://www.w3.org/2000/svg%22 viewBox=%220 0 100 100%22><!-- SVG code --></svg>");And, voilá! We get something like this:

background:

url("data:image/svg+xml,<svg xmlns=%22http://www.w3.org/2000/svg%22 viewBox=%220 0 100 100%22><foreignObject width=%22100px%22 height=%22100px%22><div xmlns=%22http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml%22 style=%22color:transparent;text-shadow: 0 0 %23e42100, -2px 2px 0 black;font-size:70px%22>🏄♀️</div></foreignObject></svg>"),

white;

background-size: 60px 60px; Other than emojis, it’s also possible to draw CSS shapes and use them as patterns. Emojis are less work, though. Just saying.

Gradient-colored emoji patterns

Instead of using plain emoji icons, we can use gradient emoji icons. To do that, skip the text shadow on the emojis. Add a gradient background behind them and use background-clip to trim the gradient background to the shape of the emojis.

color: transparent;

background: linear-gradient(45deg, blue 20%, fuchsia);

background-clip: text; /* Safari requires -webkit prefix */Then, just as before, use the combination of SVG and data URL to create the background pattern.

Translucent-colored emoji patterns

This is same as using block colored emoji icons. This time, however, we take away the opaqueness of the colors by using rgba() or hsla() values for the text shadow.

color: transparent;

text-shadow: 20px 10px rgba(0, 255, 0, .3),

0 0 red;SVG-text emoji patterns

We’ve already looked at all the working methods I could think of to create background patterns, but I feel like I should also mention this other technique I tried, which is not as widely supported as I’d hoped.

I tried placing the emoji in an SVG <text> element instead of the HTML added using <foreignObject>. But I wasn’t able to create a solid shadow behind it in all the browsers.

background:

url("data:image/svg+xml,<svg xmlns=%22http://www.w3.org/2000/svg%22 viewBox=%220 0 100 100%22><text y=%221em%22 font-size=%2270%22 fill=%22transparent%22 style=%22text-shadow: 0 0 %23e42100, -2px 2px 5px black, 0 0 6px white; ;%22>🏄♀️</text></svg>")

Just in case, I tried using CSS and SVG filters for the shadow as well, thinking that might work. It didn’t. I also tried using the stroke attribute, to at least create an outline for the emoji, but that didn’t work, either.

CSS element() patterns

I didn’t think of SVG when I first thought of converting emoji icons or CSS shapes into background images. I tried CSS element(). It’s a function that directly converts an HTML element into an image that can be referenced and used. I really like this approach, but browser support is a huge caveat, which is why I’m mentioning it here at the end.

Basically, we can drop an element in the HTML like this:

<div id=snake >🐍</div>…then pass it into the element() function to use like an image on other elements, like this:

background:

-moz-element(#snake), /* Firefox only */

linear-gradient(45deg, transparent 20px, blue 20px, blue 30px, transparent 30px)

white;

background-size: 60px 60px;

background-color: white;Now that snake emoji is technically an image that we get to include in the pattern.

Again, browser support is spotty, making this approach super experimental.

This browser support data is from Caniuse, which has more detail. A number indicates that browser supports the feature at that version and up.

Desktop

| Chrome | Firefox | IE | Edge | Safari |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 4* | No | No | No |

Mobile / Tablet

| Android Chrome | Android Firefox | Android | iOS Safari |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 68* | No | No |

In this method, the original emoji (or any CSS shape for that matter) used for the background pattern needs to render on screen for it to appear in the background pattern as well. To hide that original emoji, I used mix-blend-mode — it sort of masks out the original emoji in the HTML so it doesn’t show up on the page.

I hope you find the methods in this post useful in one way or another and learned something new in the process! Give them a try. Experiment with different emojis and CSS shapes because gradients, while cool and all, aren’t the only way to make patterns.. The background property takes multiple values, allowing us to think of creative ways to stack things.

The post Creative Background Patterns Using Gradients, CSS Shapes, and Even Emojis appeared first on CSS-Tricks.