ESLint, one of the most popular JavaScript linting utilities, quickly eclipsed more established early competitors, thanks to its open source license. The clear licensing enabled the project to become widely used but did not immediately translate into funds for its ongoing development. Despite being downloaded more than 13 million times each week, its maintainers still struggle to support the utility.

A little over a year since launching ESLint Collective to fund contributors’ efforts, the project’s leadership shared some of the successes and challenges of pursuing the sponsorship model. One effort that didn’t pan out was hiring a dedicated maintainer:

This was a difficult thing for the team to work through, and we think there’s an important lesson about open source sustainability: even though we receive donations, ESLint doesn’t bring in enough to pay maintainers full-time. When that happens, maintainers face a difficult decision: we can try to make part-time development work, but it’s hard to find other part-time work to make up the monthly income we need to make it worthwhile. In some cases, doing the part-time work makes it more difficult to find other work because you are time-constrained in a way that other freelancers are not.

One somewhat successful experiment ESLint explored is paying its five-person Technical Steering Committee (TSC), the project leadership responsible for managing releases, issues, and pull requests. Members receive $50/hour for contributions and time spent on the project, capped at a maximum of $1,000/month. The cap prevents TSC members from spending too much time on the project in addition to their day job so they don’t get burned out.

The team reports that this stipend arrangement has worked “exceedingly well” and contributions have slowly increased: “There is something to be said for paying people for valuable work: when the work is explicitly valued, people are more willing to do it.”

On larger projects like WordPress, corporate contributions are critical to its ongoing development. In recent years, the Five for the Future campaign has helped compensate many contributors as their employers pay them a salary while donating their time to work on WordPress.

Some of the major advancements in WordPress require an immense investment of time and expertise. It’s problem solving that requires working across teams for months to build complex solutions that will work for millions of users. That’s why you don’t see armies of people building Gutenberg for free. Much of the development is driven by paid employees and might not otherwise have happened without corporate donations of employee time. Automattic, Google, Yoast SEO, 10up, GoDaddy, Human Made, WebDevStudios, WP Engine, and many other companies have collectively pledged thousands of hours worth of labor per month. The diversity of companies and individuals supporting WordPress helps the project maintain stability and weather the storms of life better.

Smaller open source projects like ESLint rarely have the same resources at their disposal and have to experiment. Summarizing the one-year review of paying contributors from sponsorships, the team states: “Maintaining a project like ESLint takes a lot of work and a lot of contributions from a lot of people. The only way for that to continue is to pay people for their time.”

When even the most popular utilities struggle to gain enough sponsorships, what hope is there for smaller projects? Many utilities that have become indispensable in developers’ workflows are on a trajectory towards becoming unsustainable.

“Unfortunately, utilities like these rarely bring in any meaningful amount of money from donations, no matter how widely used or beloved they are,” OSS engineer Colin McDonnell said in his proposal for a new funding model. “Consider react-router. Even with 41.3k stars on GitHub, 3M weekly downloads from NPM, and nearly universal adoption in React-based single-page applications, it only brings in ~$17k of donations annually.”

McDonnell proposed the concept of “sponsor pools,” to fund smaller projects that are unable to benefit from existing open-source funding models. Instead of making donations on a per-project basis, open source supporters could donate a set amount into a “wallet” every month and then distribute those funds to projects they select for their sponsor pools. The key part of the implementation is that adding new projects to the pool should only take one click, reducing the psychological friction associated with supporting additional projects.

McDonnell suggested that GitHub is the only organization with the infrastructure to implement this model as an extension of GitHub Sponsors. One commenter on Hacker News proposes that Sponsors and the idea of “sponsors pool” could exist in parallel.

“I believe that there’s a meaningful difference between being the patron of a developer and feeling like you’re backing a creator with feelings and a story and a family… and wanting to be a good citizen that has an approved list of projects that I benefit from and want to support,” Pete Forde said.

“I can sponsor Matz, get his updates and feel good about knowing I am counted as a supporter AND set aside $$$ per month to contribute to all of the tools I use in my projects simply because it’s the right thing to do and I want those projects to exist for the long term. They are completely different initiatives. Patreon vs Humble Bundle, if you will.”

Tidelift is another concept that was highlighted in the HN discussion. It has a different, unique approach to funding open source work. Tidelift pools funds from the organizations using the software to support the maintainers.

“I maintain ruby grape, a mid-sized project,” Daniel Doubrovkine said. “We get $144/month from Tidelift. As more companies signup for corporate sponsorship the dollar amount increases. It’s a pool.”

Snowdrift takes a more unusual approach to pooling sponsorships where patrons “crowdmatch” each others donations to fund public goods. It runs as a non-profit co-op to fund free and open projects that serve the public interest.

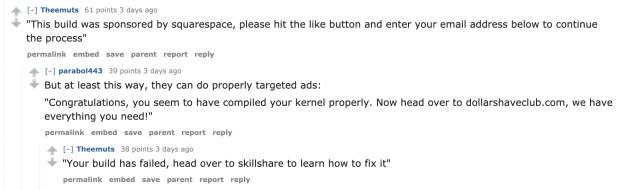

Flossbank is more specifically targeted at funding open source projects and takes technical approach to ensuring equitable contributions to the the entire dependency tree of your installed open source packages. The organization claims to provide “a free and frictionless” way to give back to maintainers. Developers can opt into curated, tech-focused ads in the terminal when installing open source packages. As an alternative, they can set a monthly donation amount to be spread across the packages they install.

No single funding model is suitable for all projects but the experiments that pool sponsorships in various ways seem to be trending, especially for supporting maintainers who may not be as skilled in marketing their efforts. The conversation around supporting utilities continues on Hacker News. WordPress developers who depend on some of these utilities may want to join in and share their experiences in funding small projects.