A web font workflow is simple, right? Choose a few nice-looking web-ready fonts, get the HTML or CSS code snippet, plop it in the project, and check if they display properly. People do this with Google Fonts a zillion times a day, dropping its <link> tag into the <head>.

Let’s see what Lighthouse has to say about this workflow.

<head> have been flagged by Lighthouse as render-blocking resources and they add a one-second delay to render? Not great.We’ve done everything by the book, documentation, and HTML standards, so why is Lighthouse telling us everything is wrong?

Let’s talk about eliminating font stylesheets as a render-blocking resource, and walk through an optimal setup that not only makes Lighthouse happy, but also overcomes the dreaded flash of unstyled text (FOUT) that usually comes with loading fonts. We’ll do all that with vanilla HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, so it can be applied to any tech stack. As a bonus, we’ll also look at a Gatsby implementation as well as a plugin that I’ve developed as a simple drop-in solution for it.

What we mean by “render-blocking” fonts

When the browser loads a website, it creates a render tree from the DOM, i.e. an object model for HTML, and CSSOM, i.e. a map of all CSS selectors. A render tree is a part of a critical render path that represents the steps that the browser goes through to render a page. For browser to render a page, it needs to load and parse the HTML document and every CSS file that is linked in that HTML.

Here’s a fairly typical font stylesheet pulled directly from Google Fonts:

@font-face {

font-family: 'Merriweather';

src: local('Merriweather'), url(https://fonts.gstatic.com/...) format('woff2');

}You might be thinking that font stylesheets are tiny in terms of file size because they usually contain, at most, a few @font-face definitions. They shouldn’t have any noticeable effect on rendering, right?

Let’s say we’re loading a CSS font file from an external CDN. When our website loads, the browser needs to wait for that file to load from the CDN and be included in the render tree. Not only that, but it also needs to wait for the font file that is referenced as a URL value in the CSS @font-face definition to be requested and loaded.

Bottom line: The font file becomes a part of the critical render path and it increases the page render delay.

(Credit: web.dev under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License)

What is the most vital part of any website to the average user? It’s the content, of course. That is why content needs to be displayed to the user as soon as possible in a website loading process. To achieve that, the critical render path needs to be reduced to critical resources (e.g. HTML and critical CSS), with everything else loaded after the page has been rendered, fonts included.

If a user is browsing an unoptimized website on a slow, unreliable connection, they will get annoyed sitting on a blank screen that’s waiting for font files and other critical resources to finish loading. The result? Unless that user is super patient, chances are they’ll just give up and close the window, thinking that the page is not loading at all.

However, if non-critical resources are deferred and the content is displayed as soon as possible, the user will be able to browse the website and ignore any missing presentational styles (like fonts) — that is, if they don’t get in the way of the content.

The optimal way to load fonts

There’s no point in reinventing the wheel here. Harry Roberts has already done a great job describing an optimal way to load web fonts. He goes into great detail with thorough research and data from Google Fonts, boiling it all down into a four-step process:

- Preconnect to the font file origin.

- Preload the font stylesheet asynchronously with low priority.

- Asynchronously load the font stylesheet and font file after the content has been rendered with JavaScript.

- Provide a fallback font for users with JavaScript turned off.

Let’s implement our font using Harry’s approach:

<!-- https://fonts.gstatic.com is the font file origin -->

<!-- It may not have the same origin as the CSS file (https://fonts.googleapis.com) -->

<link rel="preconnect"

href="https://fonts.gstatic.com"

crossorigin />

<!-- We use the full link to the CSS file in the rest of the tags -->

<link rel="preload"

as="style"

href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Merriweather&display=swap" />

<link rel="stylesheet"

href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Merriweather&display=swap"

media="print" onload="this.media='all'" />

<noscript>

<link rel="stylesheet"

href="https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Merriweather&display=swap" />

</noscript>Notice the media="print" on the font stylesheet link. Browsers automatically give print stylesheets a low priority and exclude them as a part of the critical render path. After the print stylesheet has been loaded, an onload event is fired, the media is switched to a default all value, and the font is applied to all media types (screen, print, and speech).

It’s important to note that self-hosting the fonts might also help fix render-blocking issues, but that is not always an option. Using a CDN, for example, might be unavoidable. In some cases, it’s beneficial to let a CDN do the heavy lifting when it comes to serving static resources.

Even though we’re now loading the font stylesheet and font files in the optimal non-render-blocking way, we’ve introduced a minor UX issue…

Flash of unstyled text (FOUT)

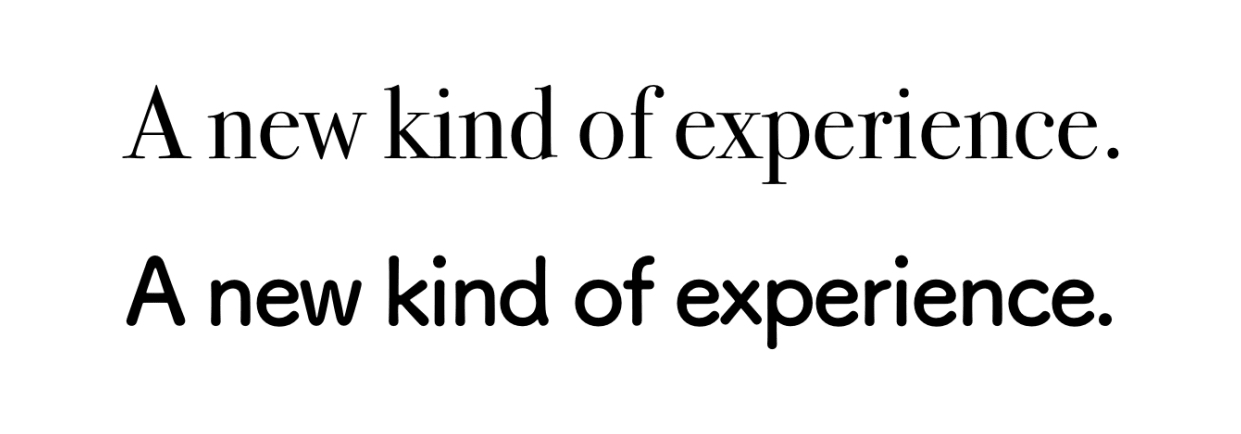

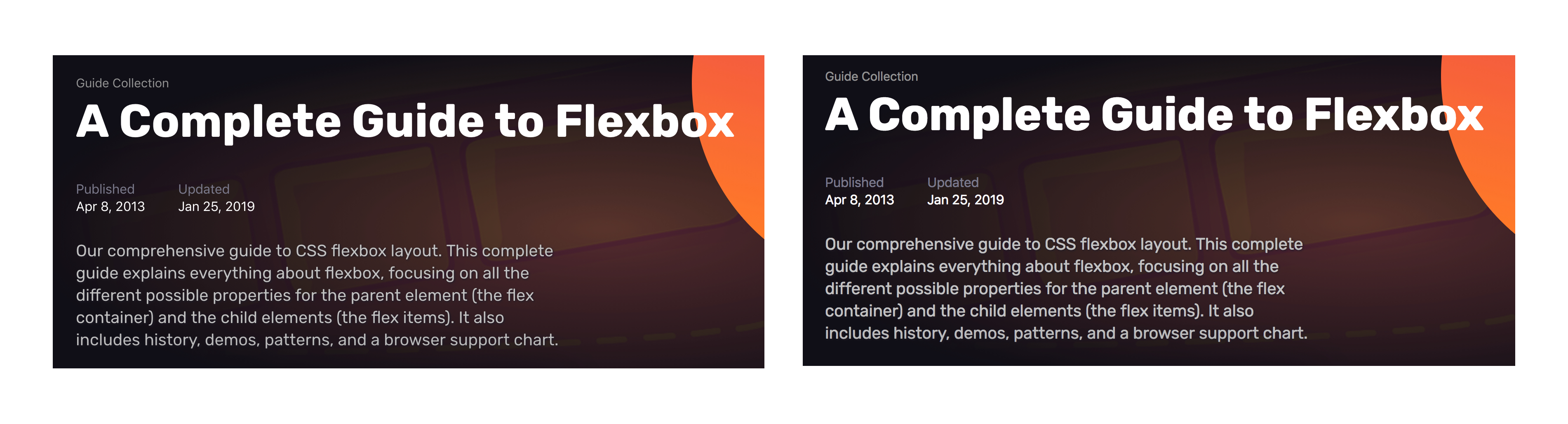

This is what we call FOUT:

Why does that happen? To eliminate a render-blocking resource, we have to load it after the page content has rendered (i.e. displayed on the screen). In the case of a low-priority font stylesheet that is loaded asynchronously after critical resources, the user can see the moment the font changes from the fallback font to the downloaded font. Not only that, the page layout might shift, resulting in some elements looking broken until the web font loads.

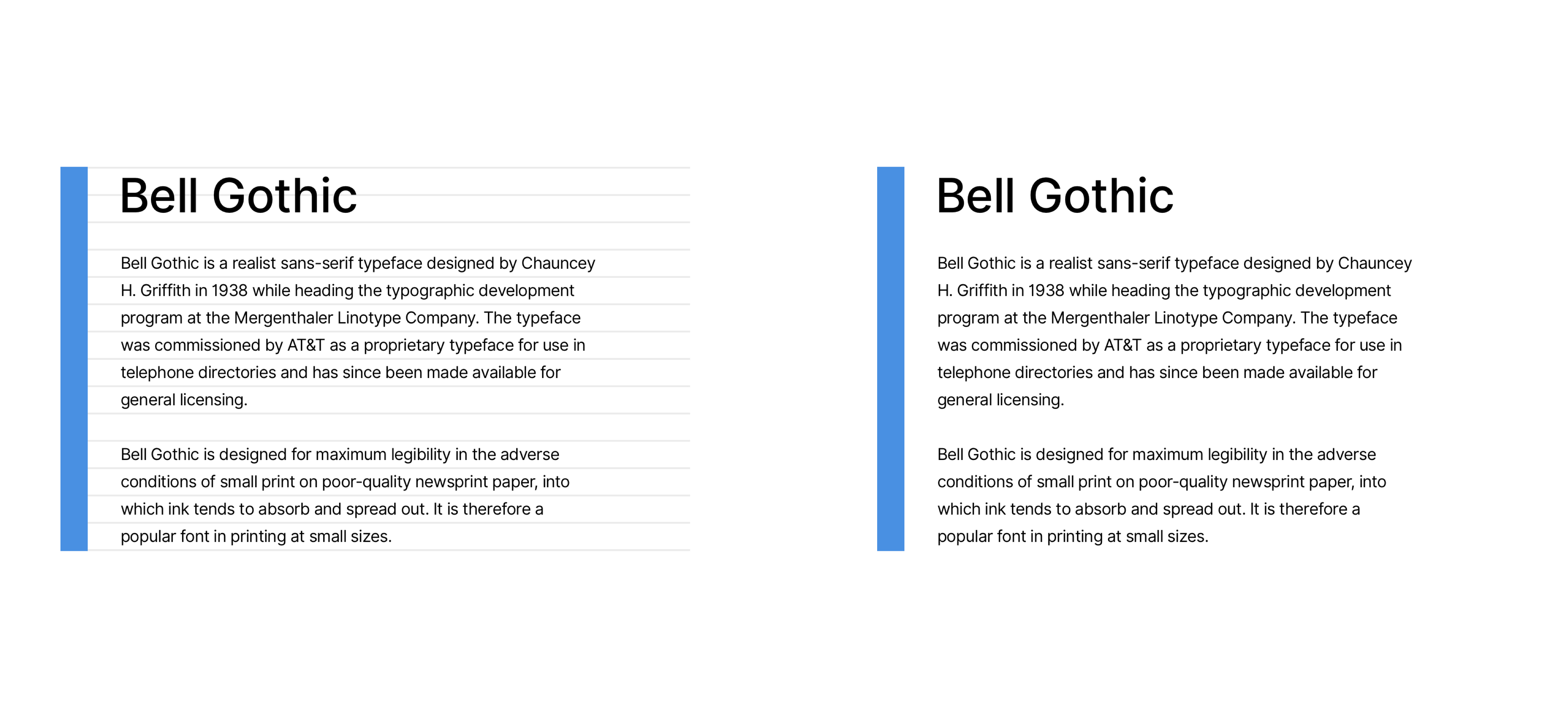

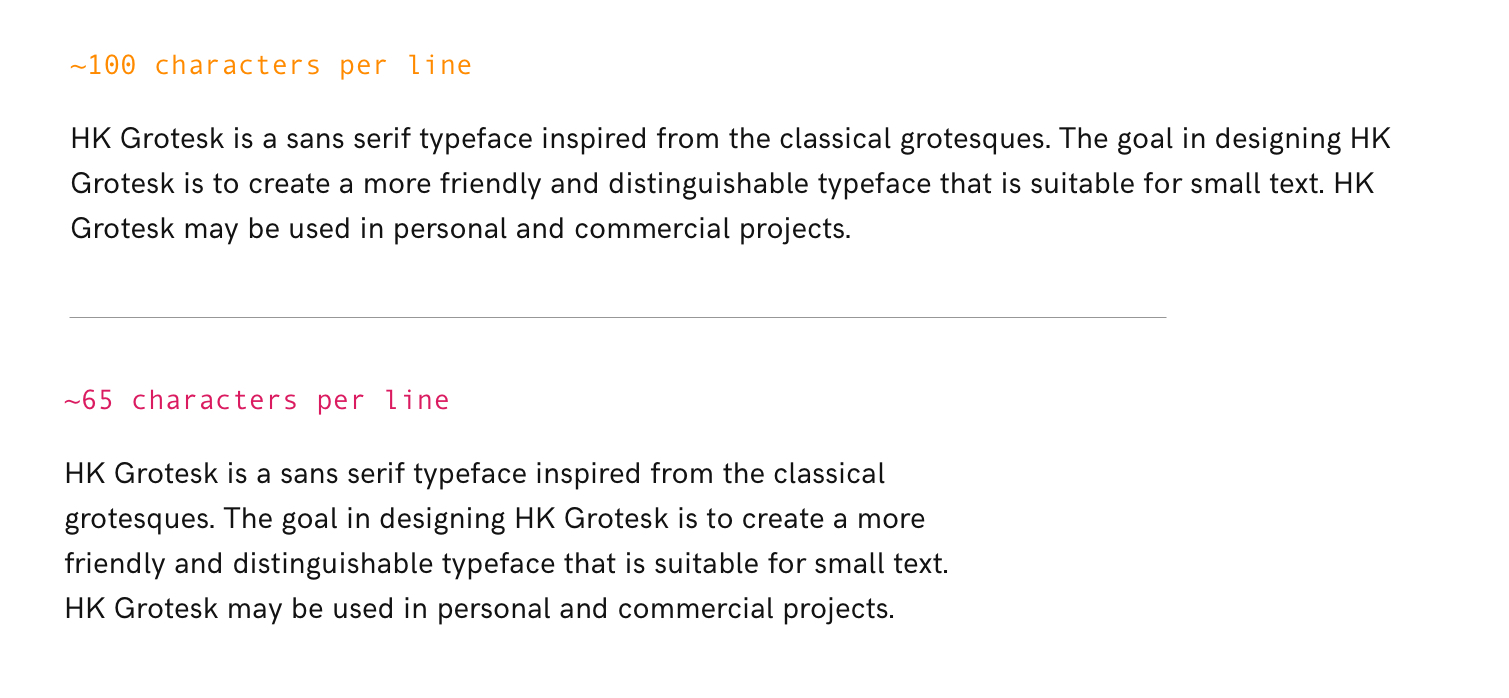

The best way to deal with FOUT is to make the transition between the fallback font and web font smooth. To achieve that we need to:

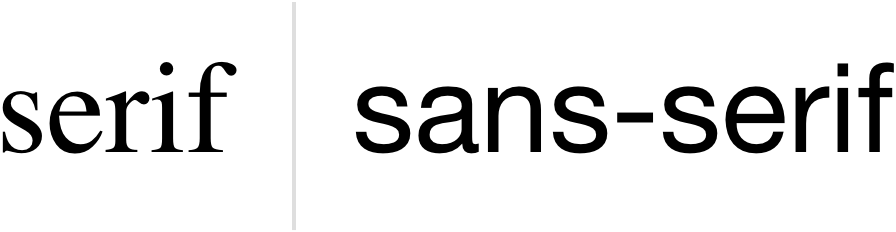

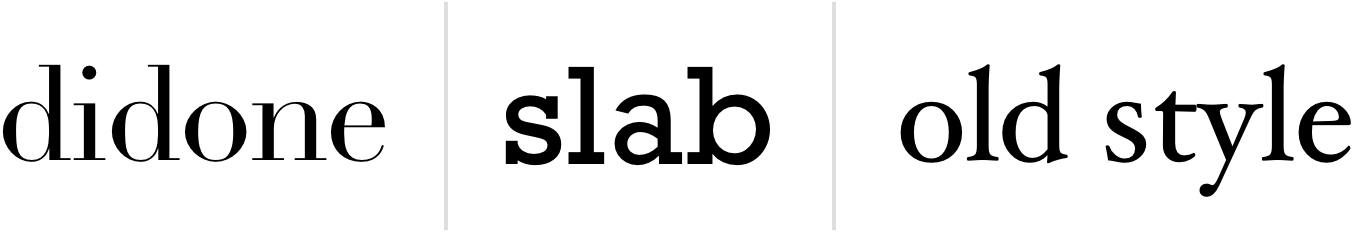

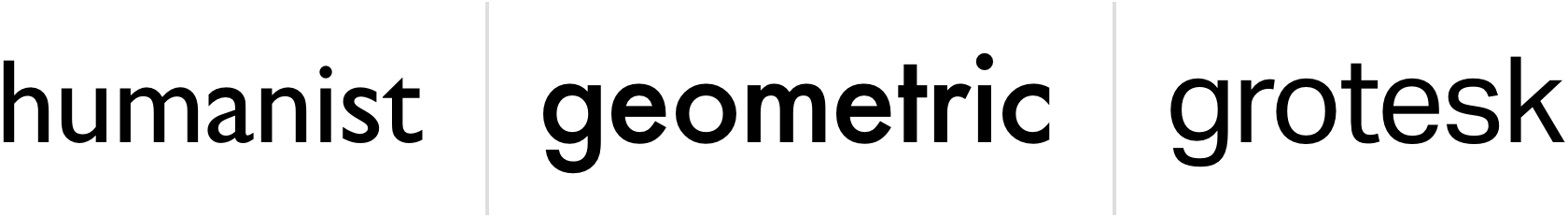

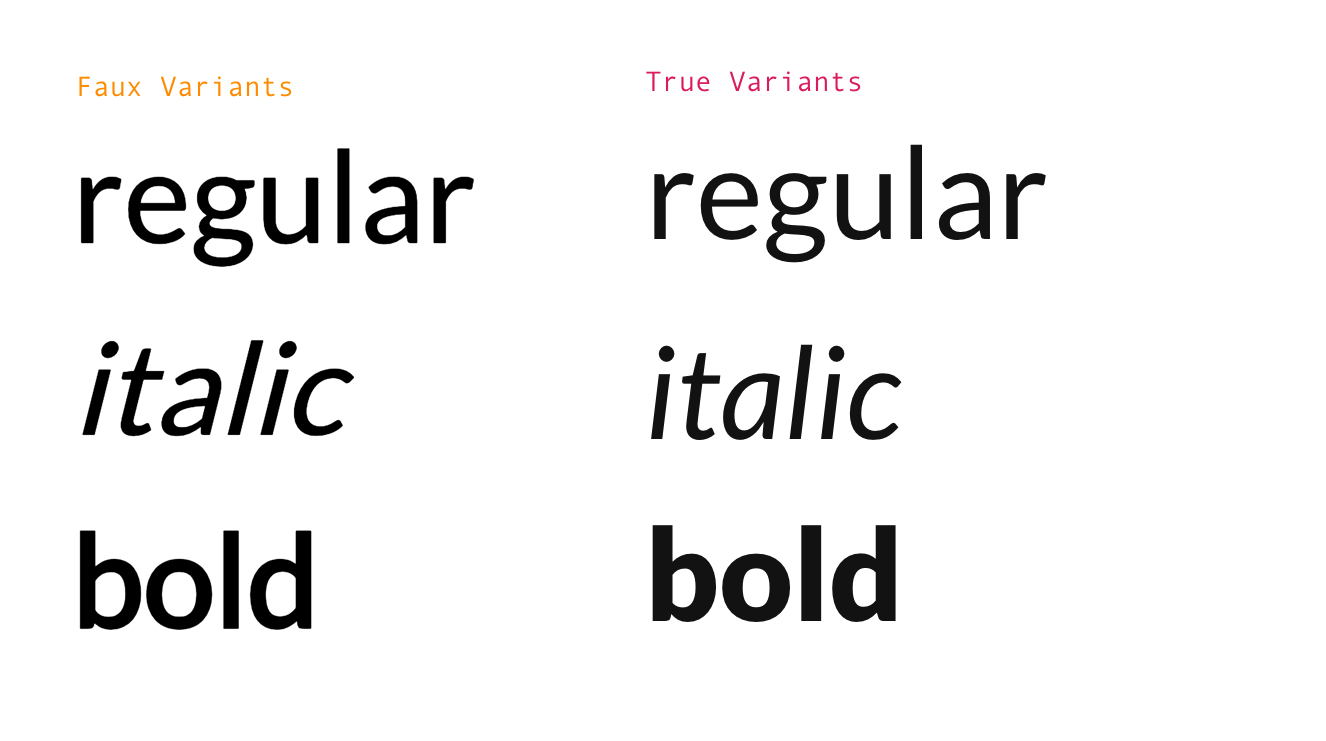

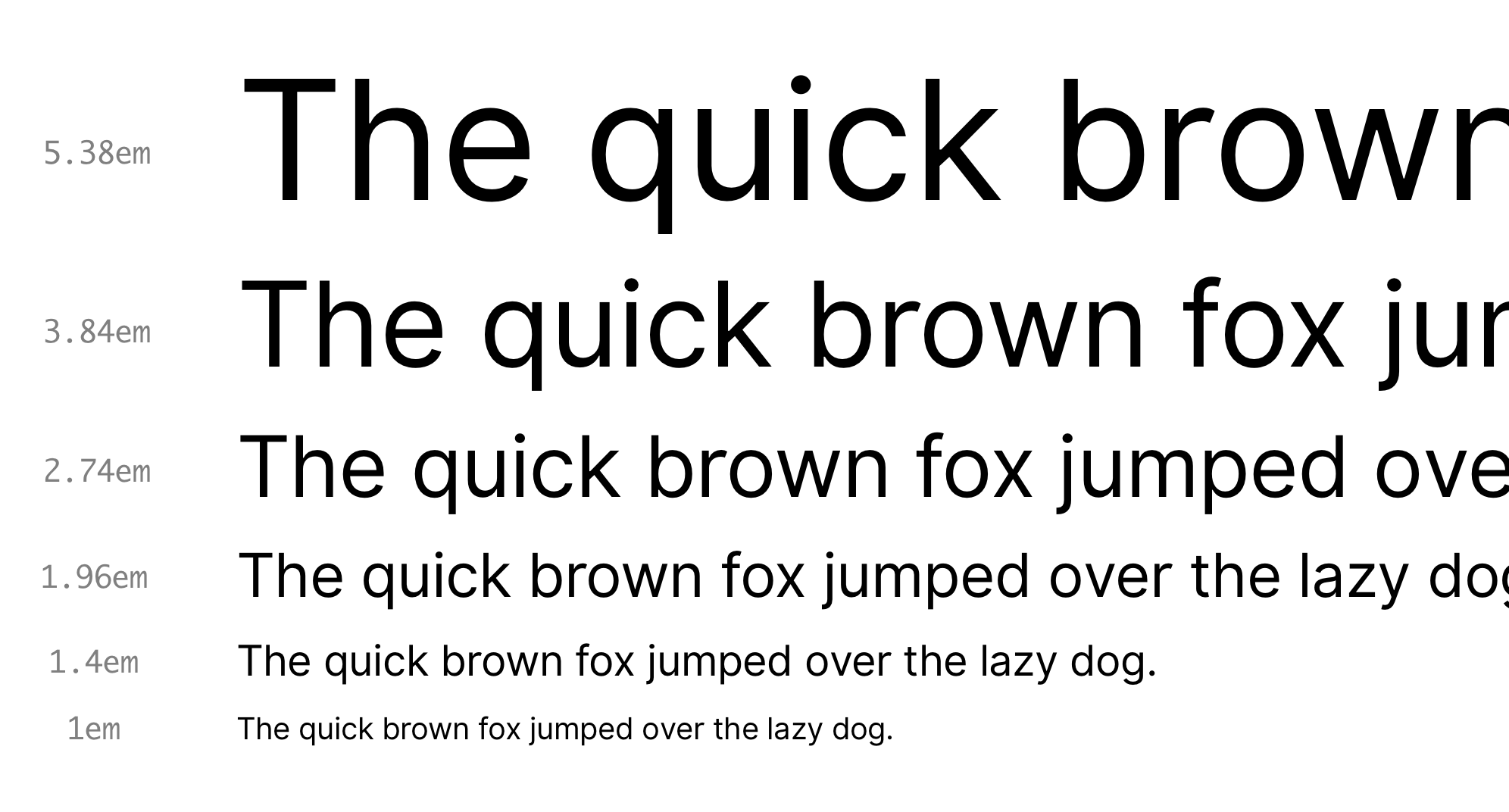

- Choose a suitable fallback system font that matches the asynchronously loaded font as closely as possible.

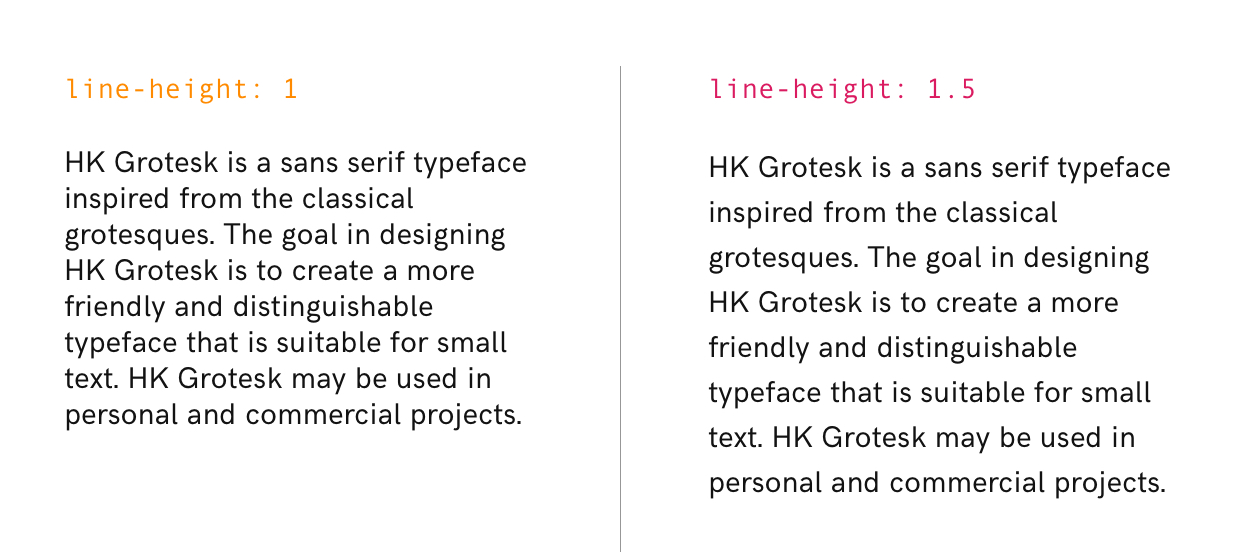

- Adjust the font styles (

font-size,line-height,letter-spacing, etc.) of the fallback font to match the characteristics of the asynchronously loaded font, again, as closely as possible. - Clear the styles for the fallback font once the asynchronously loaded font file has has rendered, and apply the styles intended for the newly loaded font.

We can use Font Style Matcher to find optimal fallback system fonts and configure them for any given web font we plan to use. Once we have styles for both the fallback font and web font ready, we can move on to the next step.

We can use the CSS font loading API to detect when our web font has loaded. Why that? Typekit’s web font loader was once one of the more popular ways to do it and, while it’s tempting to continue using it or similar libraries, we need to consider the following:

- It hasn’t been updated for over four years, meaning that if anything breaks on the plugin side or new features are required, it’s likely no one will implement and maintain them.

- We are already handling async loading efficiently using Harry Roberts’ snippet and we don’t need to rely on JavaScript to load the font.

If you ask me, using a Typekit-like library is just too much JavaScript for a simple task like this. I want to avoid using any third-party libraries and dependencies, so let’s implement the solution ourselves and try to make it is as simple and straightforward as possible, without over-engineering it.

Although the CSS Font Loading API is considered experimental technology, it has roughly 95% browser support. But regardless, we should provide a fallback if the API changes or is deprecated in the future. The risk of losing a font isn’t worth the trouble.

The CSS Font Loading API can be used to load fonts dynamically and asynchronously. We’ve already decided not to rely on JavaScript for something simple as font loading and we’ve solved it in an optimal way using plain HTML with preload and preconnect. We will use a single function from the API that will help us check if the font is loaded and available.

document.fonts.check("12px 'Merriweather'");The check() function returns true or false depending on whether the font specified in the function argument is available or not. The font size parameter value is not important for our use case and it can be set to any value. Still, we need to make sure that:

- We have at least one HTML element on a page that contains at least one character with web font declaration applied to it. In the examples, we will use the

but any character can do the job as long it’s hidden (without usingdisplay: none;) from both sighted and non-sighted users. The API tracks DOM elements that have font styles applied to them. If there are no matching elements on a page, then the API isn’t be able to determine if the font has loaded or not. - The specified font in the

check()function argument is exactly what the font is called in the CSS.

I’ve implemented the font loading listener using CSS font loading API in the following demo. For example purposes, loading fonts and the listener for it are initiated by clicking the button to simulate a page load so you can see the change occur. On regular projects, this should happen soon after the website has loaded and rendered.

Isn’t that awesome? It took us less than 30 lines of JavaScript to implement a simple font loading listener, thanks to a well-supported function from the CSS Font Loading API. We’ve also handled two possible edge cases in the process:

- Something goes wrong with the API, or some error occurs preventing the web font from loading.

- The user is browsing the website with JavaScript turned off.

Now that we have a way to detect when the font file has finished loading, we need to add styles to our fallback font to match the web font and see how to handle FOUT more effectively.

The transition between the fallback font and web font looks smooth and we’ve managed to achieve a much less noticeable FOUT! On a complex site, this change would result in a fewer layout shifts, and elements that depend on the content size wouldn’t look broken or out of place.

What’s happening under the hood

Let’s take a closer look at the code from the previous example, starting with the HTML. We have the snippet in the <head> element, allowing us to load the font asynchronously with preload, preconnect, and fallback.

<body class="no-js">

<!-- ... Website content ... -->

<div aria-visibility="hidden" class="hidden" style="font-family: '[web-font-name]'">

/* There is a non-breaking space here here */

</div>

<script>

document.getElementsByTagName("body")[0].classList.remove("no-js");

</script>

</body>Notice that we have a hardcoded .no-js class on the <body> element, which is removed the moment the HTML document has finished loading. This applies webfont styles for users with JavaScript disabled.

Secondly, remember how the CSS Font Loading API requires at least one HTML element with a single character to track the font and apply its styles? We added a <div> with a character that we are hiding from both sighted and non-sighted users in an accessible way, since we cannot use display: none;. This element has an inlined font-family: 'Merriweather' style. This allows us to smoothly switch between the fallback styles and loaded font styles, and make sure that all font files are properly tracked, regardless of whether they are used on the page or not.

Note that the character is not showing up in the code snippet but it is there!

The CSS is the most straightforward part. We can utilize the CSS classes that are hardcoded in the HTML or applied conditionally with JavaScript to handle various font loading states.

body:not(.wf-merriweather--loaded):not(.no-js) {

font-family: [fallback-system-font];

/* Fallback font styles */

}

.wf-merriweather--loaded,

.no-js {

font-family: "[web-font-name]";

/* Webfont styles */

}

/* Accessible hiding */

.hidden {

position: absolute;

overflow: hidden;

clip: rect(0 0 0 0);

height: 1px;

width: 1px;

margin: -1px;

padding: 0;

border: 0;

}JavaScript is where the magic happens. As described previously, we are checking if the font has been loaded by using the CSS Font Loading API’s check() function. Again, the font size parameter can be any value (in pixels); it’s the font family value that needs to match the name of the font that we’re loading.

var interval = null;

function fontLoadListener() {

var hasLoaded = false;

try {

hasLoaded = document.fonts.check('12px "[web-font-name]"')

} catch(error) {

console.info("CSS font loading API error", error);

fontLoadedSuccess();

return;

}

if(hasLoaded) {

fontLoadedSuccess();

}

}

function fontLoadedSuccess() {

if(interval) {

clearInterval(interval);

}

/* Apply class names */

}

interval = setInterval(fontLoadListener, 500);What’s happening here is we’re setting up our listener with fontLoadListener() that runs at regular intervals. This function should be as simple as possible so it runs efficiently within the interval. We are using the try-catch block to handle any errors and catch any issues so that web font styles still apply in the case of a JavaScript error so that the user doesn’t experience any UI issues.

Next, we’re accounting for when the font successfully loads with fontLoadedSuccess(). We need to make sure to first clear the interval so the check doesn’t unnecessarily run after it. Here we can add class names that we need in order to apply the web font styles.

And, finally, we are initiating the interval. In this example, we’ve set it up to 500ms, so the function runs twice per second.

Here’s a Gatsby implementation

Gatsby does a few things that are different compared to vanilla web development (and even the regular create-react-app tech stack) which makes implementing what we’ve covered here a bit tricky.

To make this easy, we’ll develop a local Gatsby plugin, so all code that is relevant to our font loader is located at plugins/gatsby-font-loader in the example below.

Our font loader code and config will be split across the three main Gatsby files:

- Plugin configuration (

gatsby-config.js): We’ll include the local plugin in our project, list all local and external fonts and their properties (including the font name, and the CSS file URL), and include all preconnect URLs. - Server-side code (

gatsby-ssr.js): We’ll use the config to generate and include preload and preconnect tags in the HTML<head>usingsetHeadComponentsfunction from Gatsby’s API. Then, we’ll generate the HTML snippets that hide the font and include them in HTML usingsetPostBodyComponents. - Client-side code (

gatsby-browser.js): Since this code runs after the page has loaded and after React starts up, it is already asynchronous. That means we can inject the font stylesheet links using react-helmet. We’ll also start a font loading listener to deal with FOUT.

You can check out the Gatsby implementation in the following CodeSandbox example.

I know, some of this stuff is complex. If you just want a simple drop-in solution for performant, asynchronous font loading and FOUT busting, I’ve developed a gatsby-omni-font-loader plugin just for that. It uses the code from this article and I am actively maintaining it. If you have any suggestions, bug reports, or code contributions, feel free to submit them on on GitHub.

Conclusion

Content is perhaps the most component to a user’s experience on a website. We need to make sure content gets top priority and loads as quickly as possible. That means using bare minimum presentation styles (i.e. inlined critical CSS) in the loading process. That is also why web fonts are considered non-critical in most cases — the user can still consume the content without them — so it’s perfectly fine for them to load after the page has rendered.

But that might lead to FOUT and layout shifts, so the font loading listener is needed to make a smooth switch between the fallback system font and the web font.

I’d like to hear your thoughts! Let me know in the comments how are you tackling the issue of web font loading, render-blocking resources and FOUT on your projects.

References

- Eliminate render-blocking resources (web.dev)

- Optimize WebFont loading and rendering (web.dev)

- Render Blocking CSS (Google Web Fundamentals)

- The Fastest Google Fonts (CSS Wizardry)

- CSS Basics: Fallback Font Stacks for More Robust Web Typography (CSS-Tricks)

- CSS Font Loading API (MDN)

- Font style matcher

The post How to Load Fonts in a Way That Fights FOUT and Makes Lighthouse Happy appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.