On several occasions, I’ve needed to send off an HTTP request with some data to log when a user does something like navigate to a different page or submit a form. Consider this contrived example of sending some information to an external service when a link is clicked:

<a href="/some-other-page" id="link">Go to Page</a>

<script>

document.getElementById('link').addEventListener('click', (e) => {

fetch("/log", {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json"

},

body: JSON.stringify({

some: "data"

})

});

});

</script>There’s nothing terribly complicated going on here. The link is permitted to behave as it normally would (I’m not using e.preventDefault()), but before that behavior occurs, a POST request is triggered on click. There’s no need to wait for any sort of response. I just want it to be sent to whatever service I’m hitting.

On first glance, you might expect the dispatch of that request to be synchronous, after which we’d continue navigating away from the page while some other server successfully handles that request. But as it turns out, that’s not what always happens.

Browsers don’t guarantee to preserve open HTTP requests

When something occurs to terminate a page in the browser, there’s no guarantee that an in-process HTTP request will be successful (see more about the “terminated” and other states of a page’s lifecycle). The reliability of those requests may depend on several things — network connection, application performance, and even the configuration of the external service itself.

As a result, sending data at those moments can be anything but reliable, which presents a potentially significant problem if you’re relying on those logs to make data-sensitive business decisions.

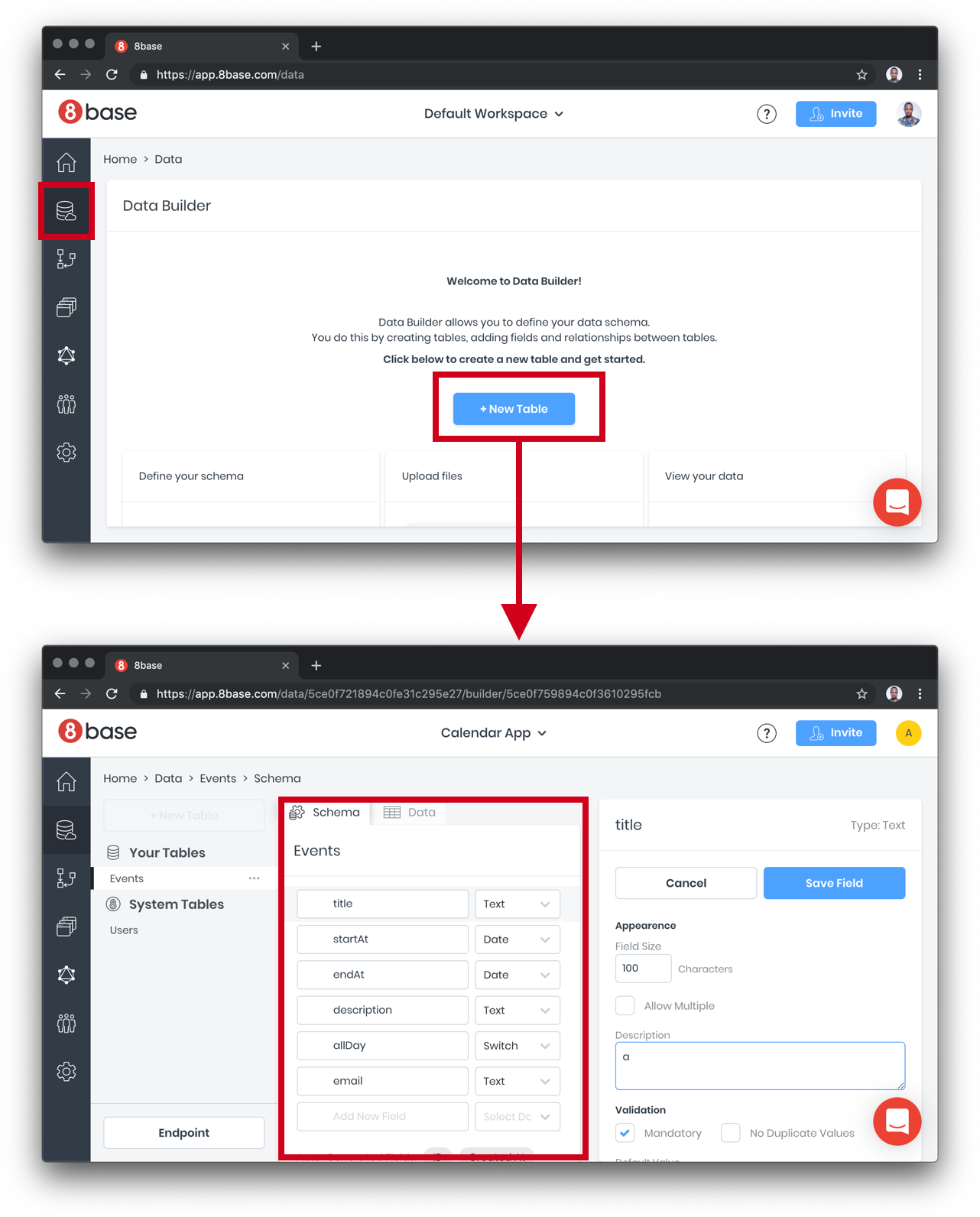

To help illustrate this unreliability, I set up a small Express application with a page using the code included above. When the link is clicked, the browser navigates to /other, but before that happens, a POST request is fired off.

While everything happens, I have the browser’s Network tab open, and I’m using a “Slow 3G” connection speed. Once the page loads and I’ve cleared the log out, things look pretty quiet:

But as soon as the link is clicked, things go awry. When navigation occurs, the request is cancelled.

And that leaves us with little confidence that the external service was actually able process the request. Just to verify this behavior, it also occurs when we navigate programmatically with window.location:

document.getElementById('link').addEventListener('click', (e) => {

+ e.preventDefault();

// Request is queued, but cancelled as soon as navigation occurs.

fetch("/log", {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json"

},

body: JSON.stringify({

some: 'data'

}),

});

+ window.location = e.target.href;

});Regardless of how or when navigation occurs and the active page is terminated, those unfinished requests are at risk for being abandoned.

But why are they cancelled?

The root of the issue is that, by default, XHR requests (via fetch or XMLHttpRequest) are asynchronous and non-blocking. As soon as the request is queued, the actual work of the request is handed off to a browser-level API behind the scenes.

As it relates to performance, this is good — you don’t want requests hogging the main thread. But it also means there’s a risk of them being deserted when a page enters into that “terminated” state, leaving no guarantee that any of that behind-the-scenes work reaches completion. Here’s how Google summarizes that specific lifecycle state:

A page is in the terminated state once it has started being unloaded and cleared from memory by the browser. No new tasks can start in this state, and in-progress tasks may be killed if they run too long.

In short, the browser is designed with the assumption that when a page is dismissed, there’s no need to continue to process any background processes queued by it.

So, what are our options?

Perhaps the most obvious approach to avoid this problem is, as much as possible, to delay the user action until the request returns a response. In the past, this has been done the wrong way by use of the synchronous flag supported within XMLHttpRequest. But using it completely blocks the main thread, causing a host of performance issues — I’ve written about some of this in the past — so the idea shouldn’t even be entertained. In fact, it’s on its way out of the platform (Chrome v80+ has already removed it).

Instead, if you’re going to take this type of approach, it’s better to wait for a Promise to resolve as a response is returned. After it’s back, you can safely perform the behavior. Using our snippet from earlier, that might look something like this:

document.getElementById('link').addEventListener('click', async (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

// Wait for response to come back...

await fetch("/log", {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json"

},

body: JSON.stringify({

some: 'data'

}),

});

// ...and THEN navigate away.

window.location = e.target.href;

});That gets the job done, but there are some non-trivial drawbacks.

First, it compromises the user’s experience by delaying the desired behavior from occurring. Collecting analytics data certainly benefits the business (and hopefully future users), but it’s less than ideal to make your present users to pay the cost to realize those benefits. Not to mention, as an external dependency, any latency or other performance issues within the service itself will be surfaced to the user. If timeouts from your analytics service cause a customer from completing a high-value action, everyone loses.

Second, this approach isn’t as reliable as it initially sounds, since some termination behaviors can’t be programmatically delayed. For example, e.preventDefault() is useless in delaying someone from closing a browser tab. So, at best, it’ll cover collecting data for some user actions, but not enough to be able to trust it comprehensively.

Instructing the browser to preserve outstanding requests

Thankfully, there are options to preserve outstanding HTTP requests that are built into the vast majority of browsers, and that don’t require user experience to be compromised.

Using Fetch’s keepalive flag

If the keepalive flag is set to true when using fetch(), the corresponding request will remain open, even if the page that initiated that request is terminated. Using our initial example, that’d make for an implementation that looks like this:

<a href="/some-other-page" id="link">Go to Page</a>

<script>

document.getElementById('link').addEventListener('click', (e) => {

fetch("/log", {

method: "POST",

headers: {

"Content-Type": "application/json"

},

body: JSON.stringify({

some: "data"

}),

keepalive: true

});

});

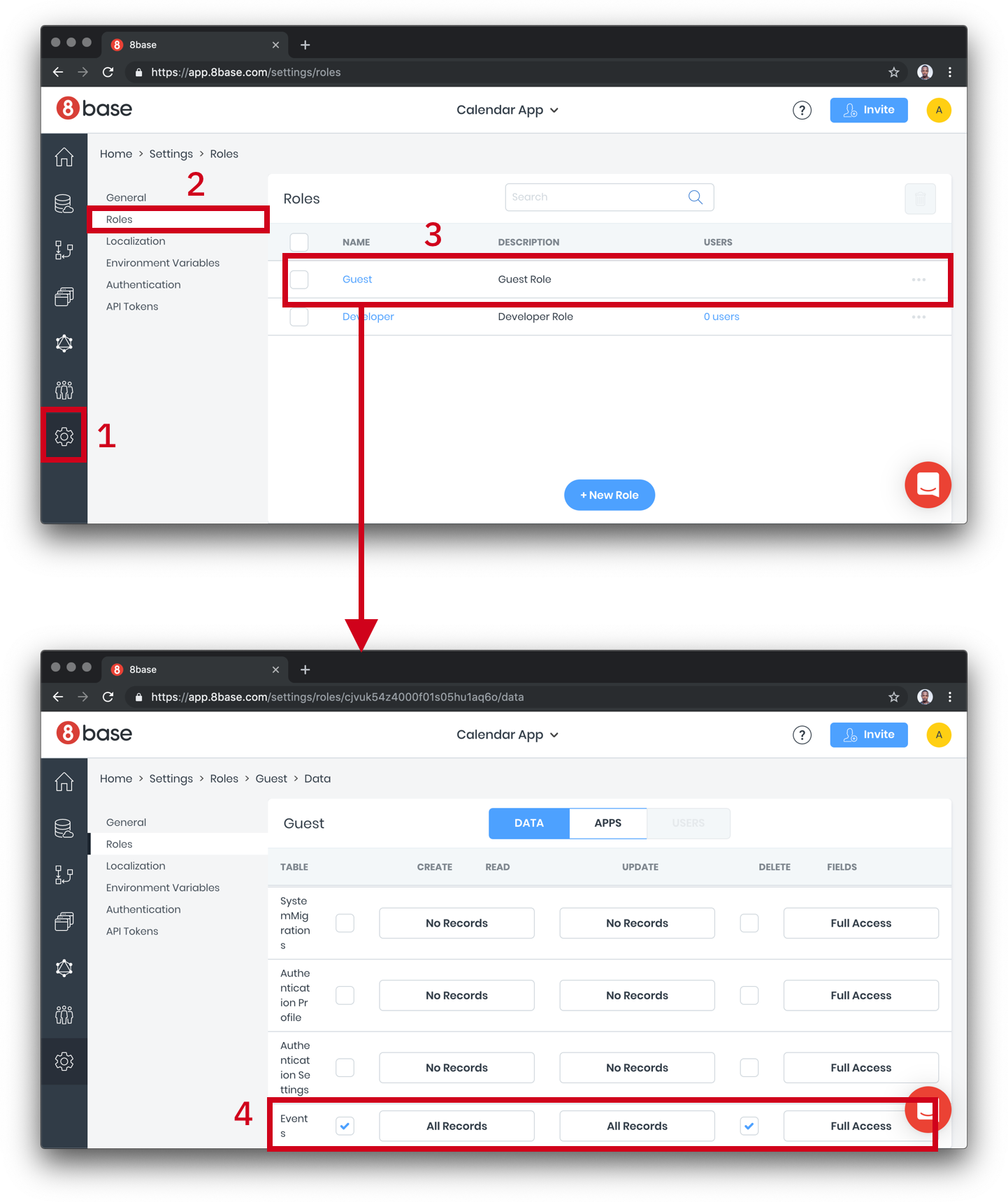

</script>When that link is clicked and page navigation occurs, no request cancellation occurs:

Instead, we’re left with an (unknown) status, simply because the active page never waited around to receive any sort of response.

A one-liner like this an easy fix, especially when it’s part of a commonly used browser API. But if you’re looking for a more focused option with a simpler interface, there’s another way with virtually the same browser support.

Using Navigator.sendBeacon()

The Navigator.sendBeacon()function is specifically intended for sending one-way requests (beacons). A basic implementation looks like this, sending a POST with stringified JSON and a “text/plain” Content-Type:

navigator.sendBeacon('/log', JSON.stringify({

some: "data"

}));But this API doesn’t permit you to send custom headers. So, in order for us to send our data as “application/json”, we’ll need to make a small tweak and use a Blob:

<a href="/some-other-page" id="link">Go to Page</a>

<script>

document.getElementById('link').addEventListener('click', (e) => {

const blob = new Blob([JSON.stringify({ some: "data" })], { type: 'application/json; charset=UTF-8' });

navigator.sendBeacon('/log', blob));

});

</script>In the end, we get the same result — a request that’s allowed to complete even after page navigation. But there’s something more going on that may give it an edge over fetch(): beacons are sent with a low priority.

To demonstrate, here’s what’s shown in the Network tab when both fetch() with keepalive and sendBeacon() are used at the same time:

By default, fetch() gets a “High” priority, while the beacon (noted as the “ping” type above) have the “Lowest” priority. For requests that aren’t critical to the functionality of the page, this is a good thing. Taken straight from the Beacon specification:

This specification defines an interface that […] minimizes resource contention with other time-critical operations, while ensuring that such requests are still processed and delivered to destination.

Put another way, sendBeacon() ensures its requests stay out of the way of those that really matter for your application and your user’s experience.

An honorable mention for the ping attribute

It’s worth mentioning that a growing number of browsers support the ping attribute. When attached to links, it’ll fire off a small POST request:

<a href="http://localhost:3000/other" ping="http://localhost:3000/log">

Go to Other Page

</a>And those requests headers will contain the page on which the link was clicked (ping-from), as well as the href value of that link (ping-to):

headers: {

'ping-from': 'http://localhost:3000/',

'ping-to': 'http://localhost:3000/other'

'content-type': 'text/ping'

// ...other headers

},It’s technically similar to sending a beacon, but has a few notable limitations:

- It’s strictly limited for use on links, which makes it a non-starter if you need to track data associated with other interactions, like button clicks or form submissions.

- Browser support is good, but not great. At the time of this writing, Firefox specifically doesn’t have it enabled by default.

- You’re unable to send any custom data along with the request. As mentioned, the most you’ll get is a couple of

ping-*headers, along with whatever other headers are along for the ride.

All things considered, ping is a good tool if you’re fine with sending simple requests and don’t want to write any custom JavaScript. But if you’re needing to send anything of more substance, it might not be the best thing to reach for.

So, which one should I reach for?

There are definitely tradeoffs to using either fetch with keepalive or sendBeacon() to send your last-second requests. To help discern which is the most appropriate for different circumstances, here are some things to consider:

You might go with fetch() + keepalive if:

- You need to easily pass custom headers with the request.

- You want to make a

GETrequest to a service, rather than aPOST. - You’re supporting older browsers (like IE) and already have a

fetchpolyfill being loaded.

But sendBeacon() might be a better choice if:

- You’re making simple service requests that don’t need much customization.

- You prefer the cleaner, more elegant API.

- You want to guarantee that your requests don’t compete with other high-priority requests being sent in the application.

Avoid repeating my mistakes

There’s a reason I chose to do a deep dive into the nature of how browsers handle in-process requests as a page is terminated. A while back, my team saw a sudden change in the frequency of a particular type of analytics log after we began firing the request just as a form was being submitted. The change was abrupt and significant — a ~30% drop from what we had been seeing historically.

Digging into the reasons this problem arose, as well as the tools that are available to avoid it again, saved the day. So, if anything, I’m hoping that understanding the nuances of these challenges help someone avoid some of the pain we ran into. Happy logging!

Reliably Send an HTTP Request as a User Leaves a Page originally published on CSS-Tricks. You should get the newsletter.