For years, a small pedantry war has been raging in our address bars. In one corner are brands like Google, Instagram, and Facebook. This group has chosen to redirect example.com to www.example.com. In the opposite corner: GitHub, DuckDuckGo, and Discord. This group has chosen to do the reverse and redirect www.example.com to example.com.

Does “WWW” belong in a URL? Some developers hold strong opinions on the subject. We’ll explore arguments for and against it after a bit of history.

What’s with the Ws?

The three Ws stand for “World Wide Web”, a late-1980s invention that introduced the world to browsers and websites. The practice of using “WWW” stems from a tradition of naming subdomains after the type of service they provide:

- a web server at www.example.com

- an FTP server at ftp.example.com

- an IRC server at irc.example.com

WWW-less domain concern 1: Leaking cookies to subdomains

Critics of “WWW-less” domains have pointed out that in certain situations, subdomain.example.com would be able to read cookies set by example.com. This may be undesirable if, for example, you are a web hosting provider that lets clients operate subdomains on your domain. While the concern is valid, the behavior was specific to Internet Explorer.

RFC 6265 standardizes how browsers treat cookies and explicitly calls out this behavior as incorrect.

Another potential source of leaks is the Domain value of any cookies set by example.com. If the Domain value is explicitly set to example.com, the cookies will also be exposed to its subdomains.

| Cookie value | Exposed to example.com | Exposed to subdomain.example.com |

|---|---|---|

secret=data | ✅ | ❌ |

secret=data; Domain=example.com | ✅ | ✅ |

In conclusion, as long as you don’t explicitly set a Domain value and your users don’t use Internet Explorer, no cookie leaks should occur.

WWW-less domain concern 2: DNS headaches

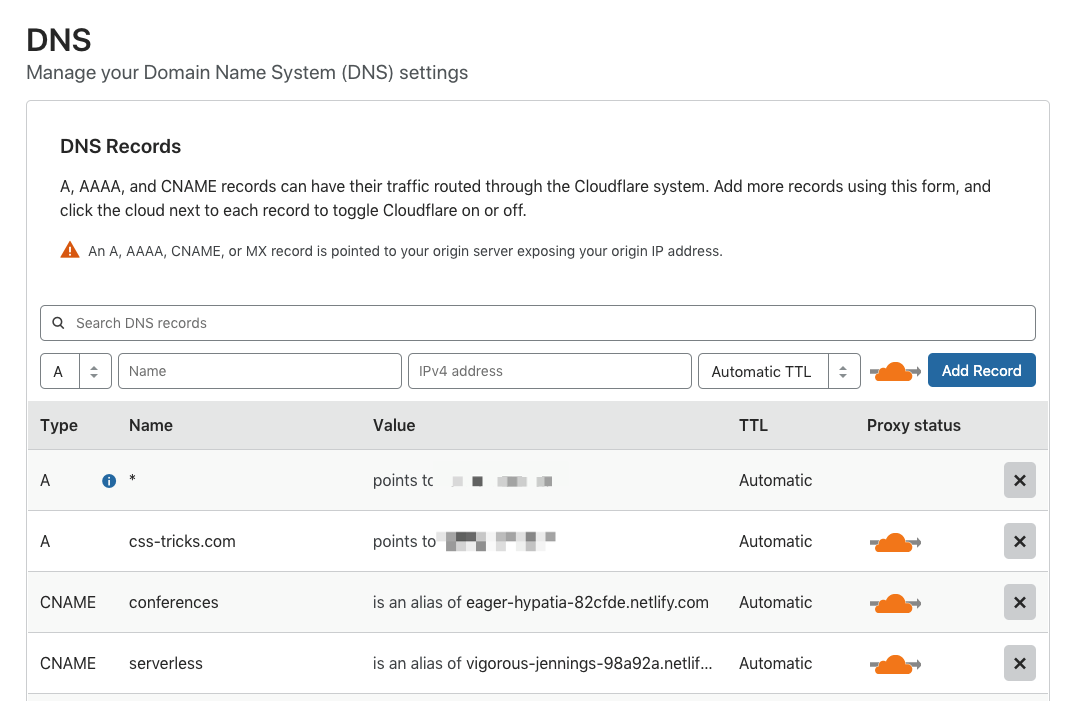

Sometimes, a “WWW-less” domain may complicate your Domain Name System (DNS) setup.

When a user types example.com into their browser’s address bar, the browser needs to know the Internet Protocol (IP) address of the web server they’re trying to visit. The browser requests this IP address from your domain’s nameservers – usually indirectly through the DNS servers of the user’s Internet Service Provider (ISP). If your nameservers are configured to respond with an A record containing the IP address, a “WWW-less” domain will work fine.

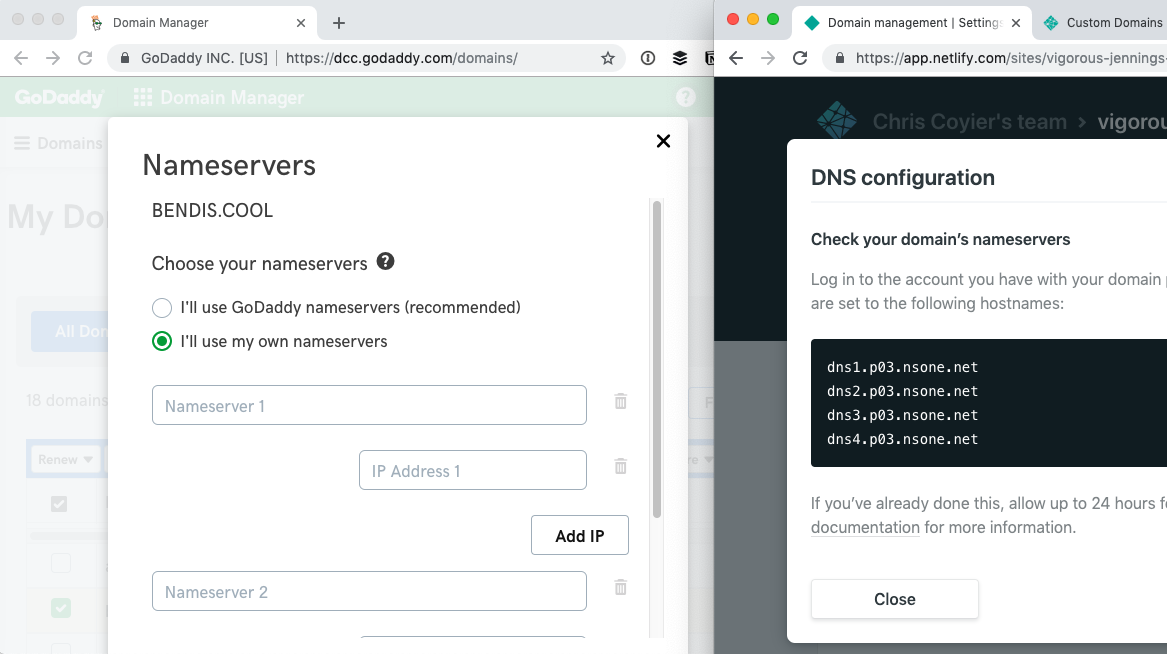

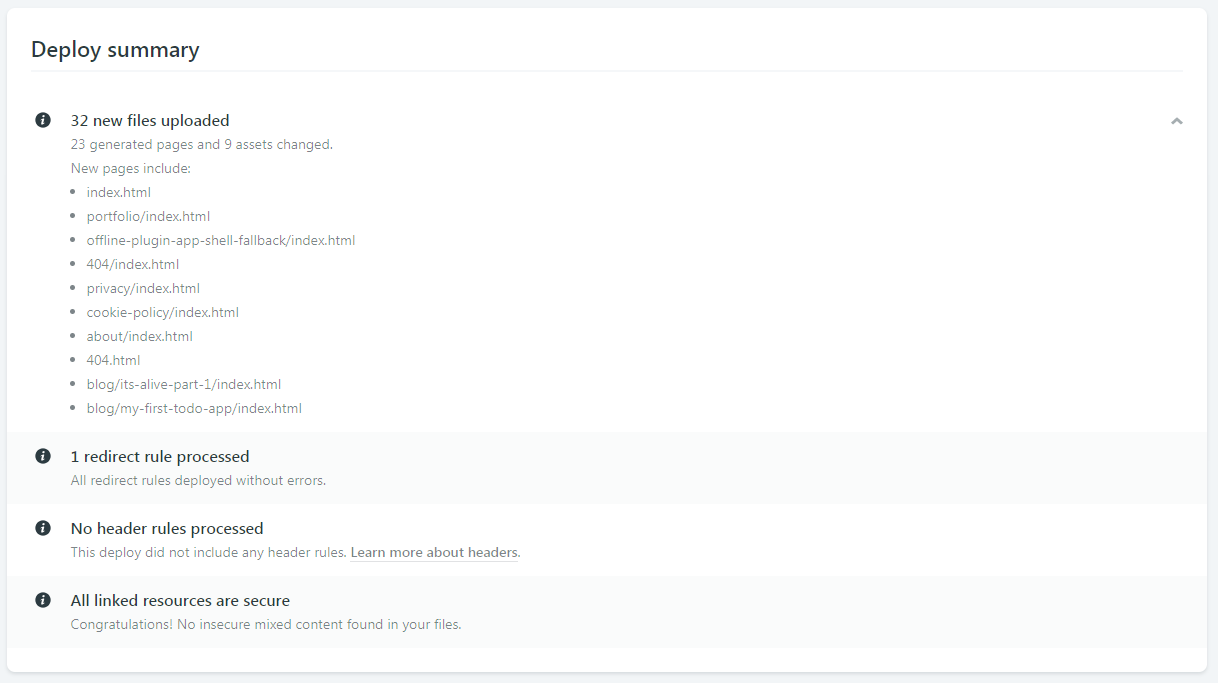

In some cases, you may want to instead use a Canonical Name (CNAME) record for your website. Such a record can declare that www.example.com is an alias of example123.somecdnprovider.com, which tells the user’s browser to instead look up the IP address of example123.somecdnprovider.com and send the HTTP request there.

Notice that the example above used a WWW subdomain. It’s not possible to define a CNAME record for example.com. As per RFC 1912, CNAME records cannot coexist with other records. If you tried to define a CNAME record for example.com, the Nameserver (NS) records for example.com containing the IP addresses of the domain’s name servers would not be allowed to exist. As a result, browsers would not be able to figure out where your name servers are.

Some DNS providers will allow you to work around this limitation. Cloudflare calls their solution CNAME flattening. With this technique, domain administrators configure a CNAME record, but their nameservers will expose an A record.

For instance, if the administrator configures a CNAME record for example.com pointing to example123.somecdnprovider.com, and an A record for example123.somecdnprovider.com exists pointing to 1.2.3.4, then Cloudflare would expose an A record for example.com pointing to 1.2.3.4.

In conclusion, while the concern is valid for domain owners who wish to use CNAME records, certain DNS providers now offer a suitable workaround.

WWW-less benefits

Most of the arguments against WWW are practical or cosmetic. “No-WWW” advocates have argued that it’s easier to say and type example.com than www.example.com (which may be less confusing for less tech-savvy users).

Opponents of the WWW subdomain have also pointed out that dropping it comes with a humble performance advantage. Website owners could shave 4 bytes off each HTTP request by doing so. While these savings could add up for high-traffic websites like Facebook, bandwidth generally isn’t a scarce resource.

WWW benefits

One practical argument in favor of WWW is in situations with newer top-level domains. For example, www.example.miami is immediately recognizable as a web address when example.miami isn’t. This is less of a concern for sites that have recognizable top-level domains like .com.

Impact on your search engine ranking

The current consensus is that your choice does not influence your search engine performance. If you wish to migrate from one to the other, you’ll want to configure permanent redirects (HTTP 301) instead of temporary ones (HTTP 302). Permanent redirects ensure that the SEO value of your old URLs transfers to the new ones.

Tips for supporting both

Sites typically pick either example.com or www.example.com as their official website and configure HTTP 301 redirects for the other. In theory, it is possible to support both www.example.com and example.com. In practice, the costs may outweigh the benefits.

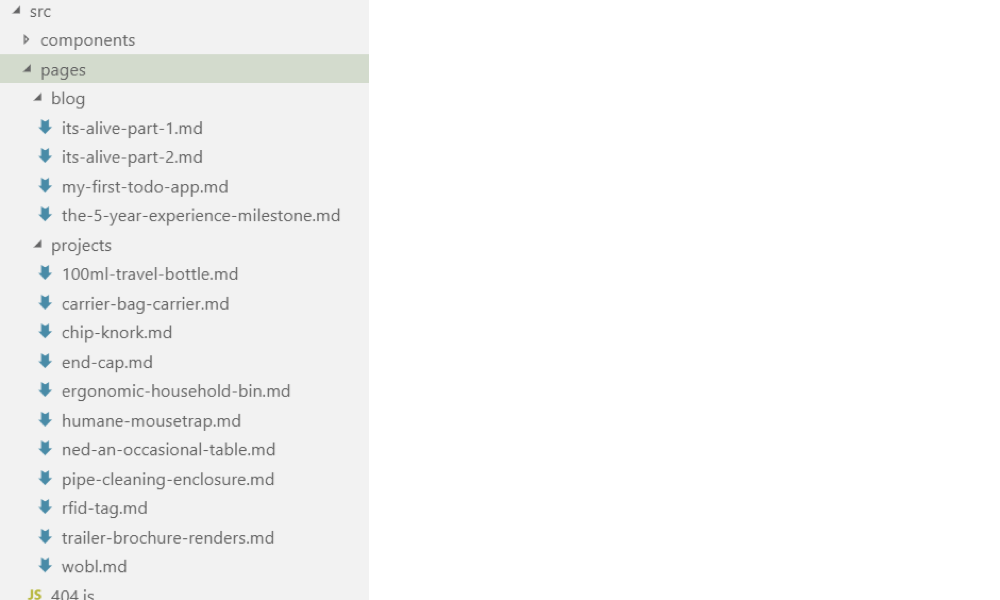

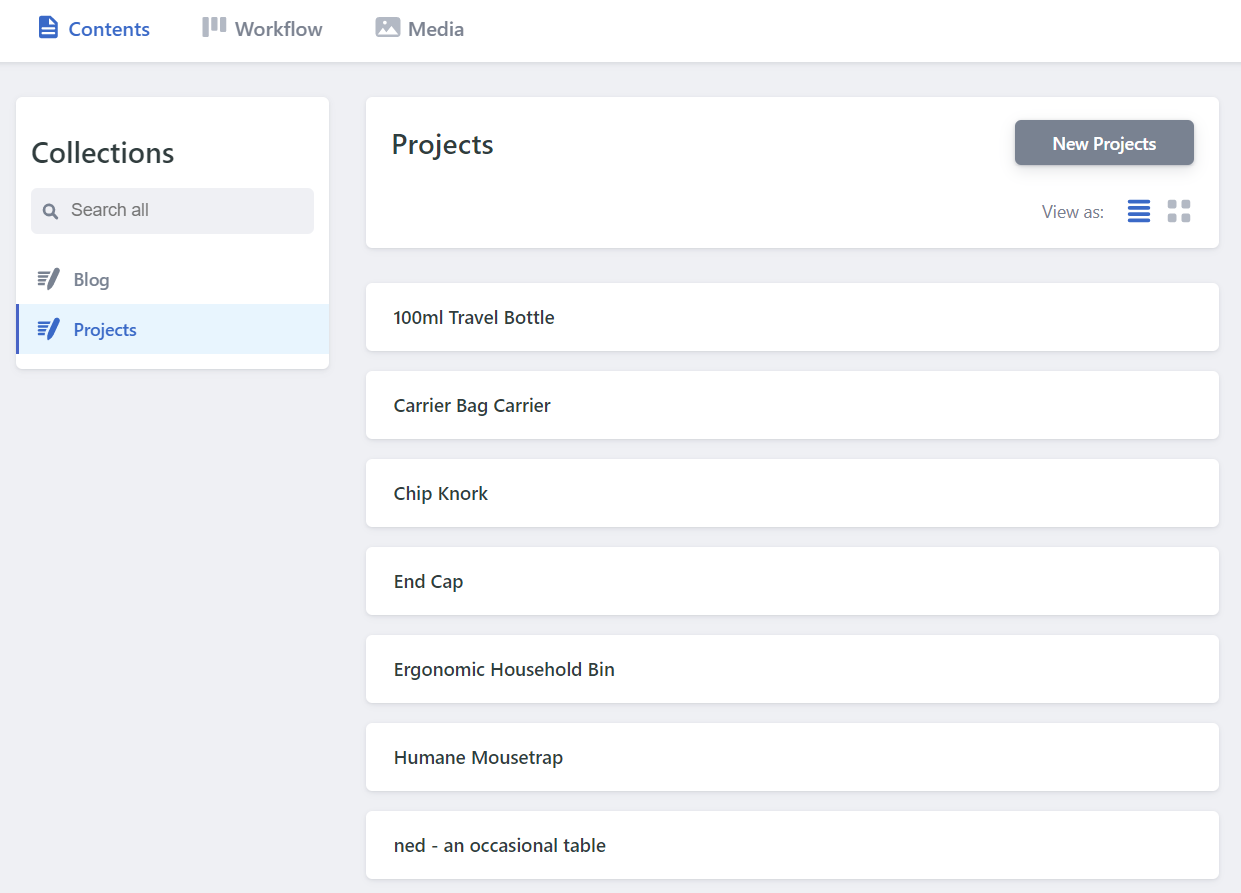

From a technical perspective, you’ll want to verify that your tech stack can handle it. Your content management system (CMS) or statically generated site would have to output internal links as relative URLs to preserve the visitor’s preferred hostname. Your analytics tools may log traffic to both hostnames separately unless you can configure the hostnames as aliases.

Lastly, you’ll need to take an extra step to safeguard your search engine performance. Google will consider the “WWW” and “non-WWW” versions of a URL to be duplicate content. To deduplicate content in its search index, Google will display whichever of the two it thinks the user will prefer – for better or worse.

To preserve control over how you appear in Google, it recommends inserting canonical link tags. First, decide which hostname will be the official (canonical) one.

For example, if you pick www.example.com, you will have to insert the following snippet in the <head> tag on https://example.com/my-article:

<link href="https://www.example.com/my-article" rel="canonical">This snippet indicates to Google that the “WWW-less” variant represents the same content. In general, Google will prefer the version you’ve marked as canonical in search results, which would be the “WWW” variant in this example.

Conclusion

Despite intense campaigning on either side, both approaches remain valid as long as you are aware of the benefits and limitations. To cover all your bases, be sure to set up permanent redirects from one to the other and you’re all set.

Does WWW still belong in URLs? originally published on CSS-Tricks, which is part of the DigitalOcean family. You should get the newsletter.