It’s true, web animation can be accessible! Sometimes it just takes a little extra effort to make sure that it is. There are strategic things we can do to make sure our animations have a positive impact on accessibility, like planning how they contribute to the overall UX and ease of use of our site. There are also more tactical considerations for making sure the animations on our site are accessible, and that’s where the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) comes in.

While different contexts can affect the details of what you need to do, the WCAG provides a number of recommendations for animated content and interactions. These include guidelines for when to provide pause and play controls, limits for blinking or flashing the screen, and advice on when to provide reduced motion options for users with motion sensitivities. If you haven’t looked at it in a while, the specification has been updated to version 2.1, and now has even more useful guidance on how we can design web animations that are accessible.

Let’s dig into each of those recommendations in more detail to see how we can apply them to our work on the web:

Pause, Stop, Hide

The first of the WCAG recommendations that applies specifically to animation is Pause, Stop, Hide. For this one, the title gives a pretty big clue into what the recommendation is all about. It states:

For any moving, blinking or scrolling information that (1) starts automatically, (2) lasts more than five seconds, and (3) is presented in parallel with other content, there is a mechanism for the user to pause, stop, or hide it unless the movement, blinking, or scrolling is part of an activity where it is essential; […]

The recommendation specifically applies to motion initiated by the web page without user interaction, and it might sound like something that doesn’t apply to UI animation work at first. Most of the durations we might use in UI animation work are far under this five second threshold individually. But there are some common patterns where this would apply. For example: auto-advancing carousels or slideshows, animated backgrounds, or animated illustrations. While each individual animation within these patterns might still be very short, the overall motion that is created often plays out over more than five seconds. This is especially true when these are designed to play on an infinite loop, which is most definitely longer than five seconds.

How to meet the Pause, Stop, Hide criteria

If you have some of these longer playing animations, you’ll need to add some kind of pause and play controls that allow users to control the motion and/or auto playing behaviour. The WCAG specification doesn’t dictate what these controls need to look like though, you have complete design control over that.

A good example of this in practice is how the article series “Dark Side of The Grid” handles the example animations. Each animated figure loops infinitely once it starts, so they provide a play/stop button for readers to play the animation when they want to see it, and stop it when they’re done. Other more decorative or illustrative animations in the article play once and then present a button to replay them, if users want to. The placement and design of the buttons also fits the aesthetic of the overall design of the article which makes them both functional and aesthetically pleasing.

Animated GIFs are something to look out for too. If you’ve got a looping animated GIF, that’s going to need some sort of pause/play controls to successfully meet this criteria. Both of the techniques mentioned in this post are helpful for pulling that off.

There are some exceptions for this recommendation, as noted by the WCAG. One exception specifically worth noting is loaders and preloaders.

Three flashes or below threshold

This recommendation is one that probably has the most research behind it because it stems from the days of broadcast TV. The main reason behind this recommendation is that significant flashing on screen has been known to trigger seizures.

In short three flashes or below threshold states:

Web pages do not contain anything that flashes more than three times in any one second period, or the flash is below the general flash and red flash thresholds.

How to meet the three flashes or below threshold criteria

The WCAG provides details on the size, ratio and viewing angle thresholds under which flashing the screen could be considered safe. But for most of us, it’s probably easiest to avoid anything that flashes more than three times in one second. I don’t think many UX designers set out to flash the screen excessively on purpose, but it can happen. For example, a design that’s going for a video game sort of feel or a glitchy vibe might involve some screen flashing that happens more frequently than three times in a second.

One specific example of a design that includes a significant amount of flashing is this article from the Huffington Post, pictured below. It’s a highly stylized piece on how millennials have a tougher go at things like jobs and saving for retirement than previous generations. Its glitchy 8-bit video game design is very on point with the theme of the article. Design-wise, it’s a great choice for the subject matter and is well executed. But there are times, as you can see from the frame-by-frame stills below, where the text color flashes more than three times a second.

This amount of flashing could be problematic for people with epilepsy or other physical reactions triggered by flashing. To their credit, the Huffington Post also provided a text-only version of the article for anyone sensitive to flashing, as Eileen mentions in this post, as well as advanced warning of the potential flashing hazard.

In general, avoiding effects that require frequent flashing is the safest way to meet this criteria. However, If you can’t avoid flashing animations in your project the WCAG provides detailed instructions around the safe thresholds for flashing the screen. Also, providing advanced warning of flashing content and an alternate version of the content without the flashing effect (like the example above) is a good thing to do as well.

The A, AA, and AAA levels of the WCAG

The WCAG has multiple levels of criteria and conformance, which is why each recommendation has a notation of what level it falls under. Level A compliance is the minimum level of conformance. Level AA is the middle level of conformance and indicates that the criteria for both level A and AA have been met. Level AAA is the highest level of conformance and requires satisfying the criteria from level A, AA and AAA. Typically, the guidelines found in level AAA require additional effort to meet. (If you want to learn more about these levels and what’s included in them outside of the animation-related recommendations we’re covering here, I’ve put together a list of helpful resources at the end of this article.)

In general, most people are aiming for level AA compliance when they say they are making an accessible website. This is also the level you might see requested in an RFP or project brief. The last two guidelines we discussed fall under the level AA criteria and, therefore, must be met to claim level AA compliance. The next guideline, however, is part of the level AAA criteria. Even though it’s outside of the typical level of conformance, it’s a very useful recommendation to take into consideration if your project relies significantly on animation. I highly recommend implementing it in your work.

Animation from interactions

This guideline covers a different kind of animation than the previous two. While the first two are generally applied to animation that’s initiated by the web page itself, this one applies to animation initiated by user interaction. More specifically, it states:

Motion animation triggered by interaction can be disabled, unless the animation is essential to the functionality or the information being conveyed.

At first read, the term “motion animation” can be confusing since we typically use the terms “motion” and “animation” interchangeably. It might seem overly specific at first, but it makes sense to get this specific in this case. The WCAG defines motion animation as animation that is used to ”create the illusion of movement”, and specifies that “motion animation does not include changes of color, blurring or opacity.”

Essentially, the term motion animation is used to indicate that certain types of animation create the sense of movement, while others do not. It’s those animations that create a sense of movement that concerns this guideline. It’s important to keep that distinction in mind when discussing animation and accessibility to help make sure you focus your efforts efficiently. If we were to express this distinction in a very eyeball-like Venn Diagram, it would look like this:

Over the last few years, we’ve come to realize that some types of motion on screen, even as part of an interface, can cause people with motion sensitivities to become physically ill. So this is why we might want to consider creating a reduced motion mode in our work. I wrote more about the kinds of motion effects that are most likely to be triggering in this article, and this post from the WebKit blog covers some examples in detail.

How to meet the animation from interactions criteria

The WCAG suggests we avoid unnecessary animation, provide a control for users to turn off any non-essential motion, or take advantage of the reduced motion setting in operating systems and user agents. Let’s look at each of these in a bit more detail. There are a few different things we can do to help avoid exposing people to animation that might make them dizzy, nauseous, or worse.

Avoid unnecessary animation

Context and expectations also play a role here. The amount of motion you might reasonably expect to encounter on a website for a movie or video game is very different from what you might reasonably expect to encounter on say a government site or construction company’s site. The same amazing effects that might fit in just fine on a video game’s site would feel unnecessary or out of place on, say, a government website. Consider the context and expectations that apply to your site and whether the amount of animation you’re using in your design fits that context.

Provide a way for users to turn off potentially problematic motion animation

If you have motion in your product that might be a trigger for folks with motion sensitivities, providing a way for users to avoid those triggering animations is the responsible thing to do. Based on the WCAG’s definition, any effect that could be considered motion animation should be one that includes a reduced version.

Parallax effects are a good example. Those are universally problematic for folks with motion sensitivities based on my own research, yet it’s also still a very popular technique. While it wouldn’t be realistic to call for an end to all parallax effects entirely, implementing parallax responsibly requires giving your users some level of control to turn off that triggering motion.

Typically, this is interpreted as including a toggle, setting, or preference for users to indicate their preference for reduced motion, and providing reduced versions of those motion animation effects when it’s activated. The Netlify 1 Million Devs site is one example of a motion toggle in action, and the official Animal Crossing site has one too.

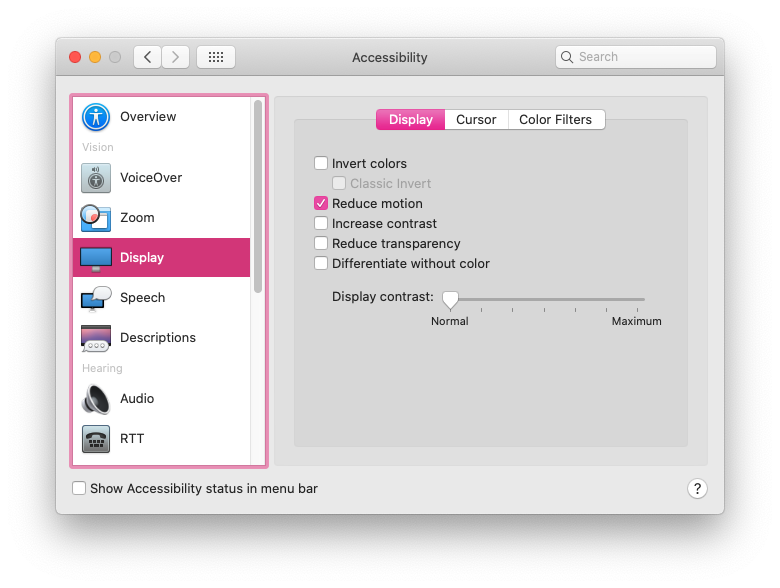

Take advantage of the reduce motion feature

Sites or apps that don’t rely heavily on large amounts of motion might find that a custom toggle isn’t the right strategy for them, and instead use the prefers-reduced-motion media query on its own. This allows you to provide a reduced version of highly animated content when that preference is present globally via the user’s operating system. It’s also a setting they can set in one place and have it affect a variety of content they encounter. That makes it a great tool for us to use to detect and respond to a user’s need for reduced motion.

I’ve written about using prefers-reduced-motion in detail over at Smashing Magazine, and it’s also been covered by other articles on this site. In short, it allows us to access someone’s OS-level motion preference via a media query. We can access it in CSS or JavaScript and use the returned value to provide a reduced motion experience for those who want it. For example, we could do this to create a reduced motion variation of a bouncing CSS animation:

/* A constant bouncing motion effect applied to the title */

h2 {

animation: bouncing 1.5s linear infinite alternate;

}

/* Replace it with a safer effect when prefers-reduced-motion returns true */

@media (prefers-reduced-motion: reduce) {

h2 {

animation: fade 0.5s ease-in both;

}

}Some sites opt to use both a custom toggle and reduced motion preferences together. If you go to the site with reduced motion requested in your operating system settings, you automatically get the reduced motion mode. This two-pronged approach is a great strategy for sites with large amounts of motion. Marcy Sutton covers the basics of how to set up this approach in her egghead.io course, as well as in this CodePen demo.

Use these guidelines for your next animation project

There you have it, everything the WCAG says about animation explained in one place. I hope this article will help you to confidently make your web animation work accessible. Sometimes it takes a little extra effort, but that extra effort is totally worth it when it means you’ve expanded the number of people who can meaningfully interact with your site.

This article focused on the recommendations specific to animation, but animation isn’t the only place in our work where accessibility considerations can make a big impact. There are some great resources on accessibility out there that cover a more holistic view on accessibility. One of my favorites is the book Accessibility for Everyone by Lara Kalbag. Sites like WebAIM and the A11y Project are great ones to check out for a wealth of resources. If you’re doing a lot of your animation work with SVG, Heather’s SVG accessibility article is a good resource as well. I highly recommend checking out these resources if you haven’t already.

The post Accessible Web Animation: The WCAG on Animation Explained appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.