Animations can make a site stand out. Or, they can just as easily kill the experience. When working with web animations, there are a few things that could go wrong like adding animations that serve no purpose, setting durations that are too long or too quick, or not using right type of animation in the first place. Even if all of these things are done correctly, an animation style may not feel good, especially if they are not in sync with other animations or in line with the overall personality of the site.

Another important thing to note is that not all digital experiences should share the exact same animations. A marketing website might need different animations than a product website or a mobile app. Although the same basic principles of motion apply for all, there’re some nuances based on content type and screen size.

For example, say you want to make a boring form more exciting to fill out. You add some delightful animations in each step moving forward, but is that a good idea for a form you know a user needs to visit and fill often? Watching the same animations over and over could get annoying in that case.

Clearly, there are conditions and considerations that will serve animations well. In this article, we’ll discuss about adding animations into product websites. Let’s dig into that a bit and lay down some ground rules for working with them. Not so much a manifesto, but more like a baseline we can reference and sort of rally around.

First off, what’s a good situation for an animation?

When used well, an animation is almost like content — it provides context and has meaning that helps inform the user that something has happened and even what to expect next. Here are a few good situations where animation can do exactly that.

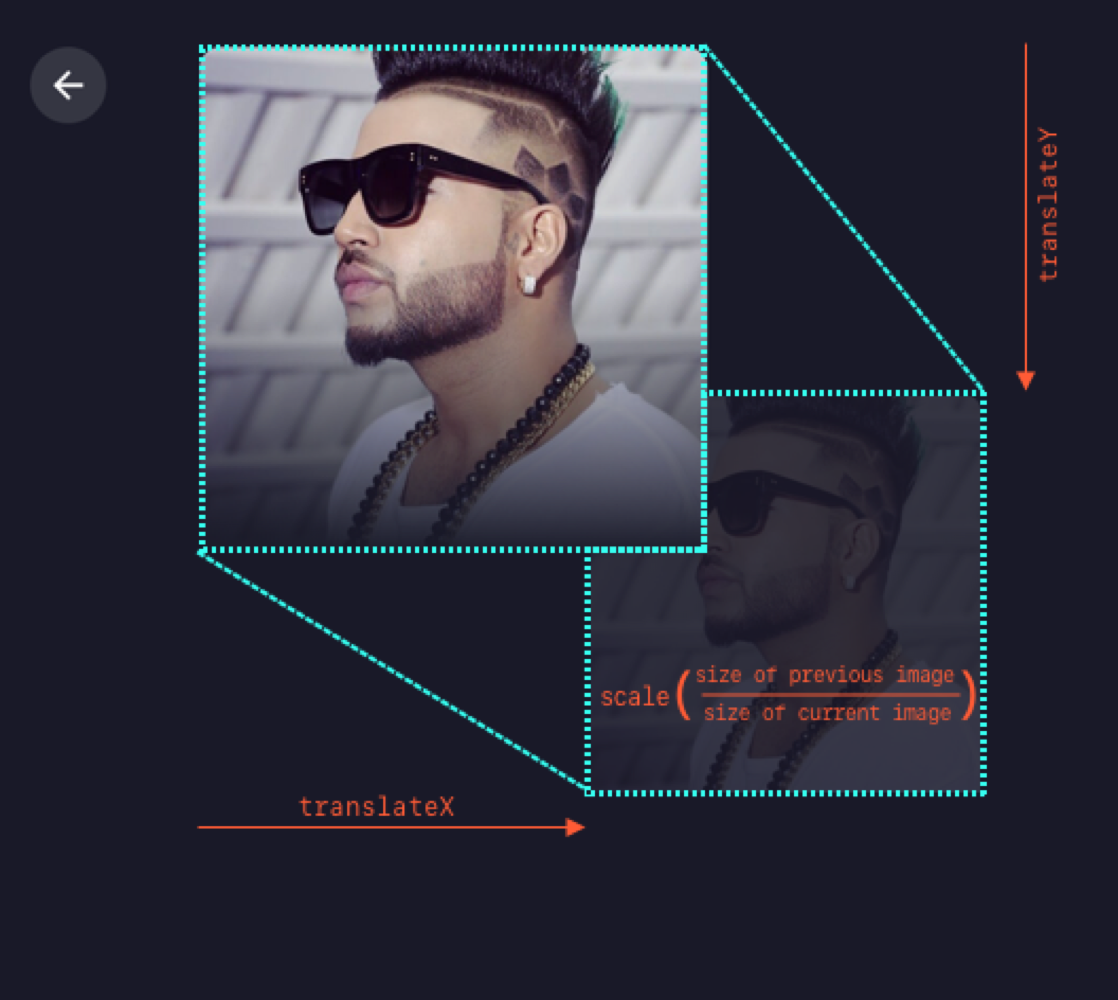

Transitioning UI blocks

This might be the most common use case for animations. When a UI block is moved from its original position, or is added or removed from the DOM, it’s a good idea to let users see that happen.

Loading content

A loading animation is something we’ve all seen and encountered at some point in time! If not, a quick trip to CodePen shows you just how popular loading animations are. They’re ideal as placehholders for content, where users are not only given a hint at what to expect when the content loads, but confidence that something is being loaded at all.

Besides making the site feel fast, it also avoids janky content reflow, which can be super disorienting as elements render at different times.

Client side rendering is so interesting. Look at this janky loading experience. The page itself isn’t particularly slow, but it loads in very awkwardly. A whole thing front-end devs are going to have to get good at. pic.twitter.com/sMcD4nsL98

— Chris Coyier (@chriscoyier) October 30, 2018

Loading placeholders are best, of course, when you know the height of content blocks ahead of time.

Hinting

This is generally a one-time animation where the point is to give users a hint for where to look or what to do next. Some UIs are complex by nature. A little glow or ripple can help guide users through the process of completing a task or calling out a particular feature.

It doesn’t have to be all up in the user’s face. Instead, a little visual hint that informs without taking over the entire experience will do just fine.

Micro-interactions

Generally used on individual elements, micro-interactions give users instant visual feedback after performing an action. They instill confidence that a performed action has taken place and that something happened as a result — all while adding a little delight at the same time.

These do not have to be fancy, like Twitter’s heart animation, but they totally should indicate some kind of feedback or response to the user’s action. Just check out how subtle — yet delightful — that is when a user does something as small as adding an item from one line to another:

OK, so when should we avoid animations?

We’ve just seen handful of situations where animations make a lot of sense. Let’s spell out the opposite conditions where animations generally contribute very little or nothing to the user experience. In other words, they become noticeable for bad reasons and are probably best left out of the equation.

Route transitions

Yes, we usually don’t see these sorts of animations on product websites but it’s worth mentioning to understand why they don’t make sense. These transitions work better on mobile apps because of the small screen area. On desktop screens there’s much larger area to animate. To animate the whole content smoothly, you’ll require to set more duration than on mobile screen. This will simply annoy the users making them wait to see the content as they are already used to see instant content visibility on the web. And in the worst cases, route transitions can not only be distracting, but a severe accessibility concern when it comes to motion sensitivity.

On initial load of page content

You may do it in marketing websites when you want to educate users or move their focus to a particular block. For product websites, it will be again annoying to see the same animation each time users navigates between pages.

When it’s unexpected

It’s a good idea to consider a user’s state of mind while they use a particular feature. Is visual feedback expected where the animation is being used? If not, it can confuse more than it helps.

For example, checkout this calculator app. There’s nothing new in the UI pattern when numbers are entered and calculations run. Users already know where to focus. There’s no point in making users wait before they can see results or surprise them with something that provides no additional meaning or benefit.

When you’re unsure how well it performs

It’s worth bearing in mind that not all devices, internet connections, and browsers are equal in the eyes of animation. Eric Bailey sums this up nicely in his deep-dive on the prefers-reduced-motion media query:

We also need to acknowledge that not every device that can access the web can also render animation, or render animation smoothly. When animation is used on a low-power or low quality device that “technically” supports it, the overall user experience suffers. Some people even deliberately seek this experience out as a feature.

The heading above that quote is a sage reminder: Animation is progressive enhancement. If we plan on using an animation — especially ones that threaten to dominate the experience — we’ve gotta at least consider a way to opt out of it and whether the experience still works without the animation. prefers-reduced-motion is the best place to start.

When the purpose isn’t clear

Lastly, I’d say don’t add animations wherever you’re not absolutely sure about the purpose it serves. Superfluous animation can be distracting and hurt more than it helps. This tweet from 2018 is still very true:

Web design in 2018

— Thomas #BlackLivesMatter (@thomasfuchs) March 27, 2018

428 dependencies

142 seconds compile time

5 MB of JavaScript

0 clue as to basic UI interactions pic.twitter.com/1GAAQS4td8

How long should an animation last?

The length of an animation is just as important as the type of animation being used. Wait too long, and the animation can appear to drag on. Go too fast, and the nice details of the animation can get lost (in best cases) or completely disorient the user (in worse cases).

So, how long should we set the duration of an animation? I’ll give you a classic answer: It depends.

The bigger the distance, generally the longer the duration

Animations (like the ones we looked at earlier) can be limited to a short duration. But if we’re taking about a massive transition where an object is traveling a long distance, we may feel it needs something a little longer to make sure things don’t move too fast. But avoid using duration longer than 400ms.

Check out this example. Notice how the content takes a little longer to transition because it has a greater distance to travel. But also notice that the it doesn’t have to last too long because the object that leaves fades into the object that enters, and the object that enters comes at a shorter distance rather than making it travel across the entire screen.

Goes to show that even big animations can be optimized in ways that make it feel shorter without getting lost in the mix.

Use a shorter duration when the user triggers the action

This is important and a common mistake. If the user already expects something to happen — and the focus is already clearly where it should be — then there’s no point in making the user wait seconds to complete what they already expect.

On the other hand, if the change is automatically triggered by the system, a longer duration makes sense, as it will allow the user to catch up to speed with the change taking place. Think of tooltips or modals that are not triggered by the user do not require a their immediate attention.

Enter and exit animations can have different durations

Sometimes it makes sense to keep the animation for an object that is entering view a little faster than an animation for an object that is exiting, especially when the user is expecting to see that content change.

Take the previous example of dropdown menu. When a user clicks on it, they’d want to see the menu items right away — at least, I wouldn’t have to wait to see menu items. When the user clicks, let the submenu enter quickly and then smoothly leave when it’s dismissed so that it avoids distracting the user on the way out, when it’s no longer needed.

But this does not apply for large UI blocks. On larger blocks, for most cases, a duration longer than 200ms is required. In such cases, reversing the durations and letting a block exit faster than it entered ensures it won’t block the existing page view.

Animation duration across the product should be in sync with each other and with the brand’s personality

I’ve came across many products where one feature has really nice animations and another is simply too quick, slow or lacks any animation at all.

Even worse is when animations within the same feature aren’t in sync.

That’s where having a style guide with thoughtful animation guidelines that can be used consistently across the experience can be a huge help.

How simple is too simple? Or how complex is too complex?

The complexity of an animation ought to be based on how frequently users are expected to encounter it, among the other things we’ve looked at so far. The more often users are expected to see it, the simpler the animation should be. This should override the previous rules of duration where necessary.

For example, the below animation would work in a main menu, but using the same staggering effect in drop-down menus across the product is just too much to take in. There is indeed a point of diminishing returns in animations, just as there is in economics.

But, hey, if this sort of complex animation is used sparingly in intentional instances, then it can be incredibly delightful!

But yes, you can be creative with the animations where there’s a decision pending at the user or while processing data. This makes waiting times more engaging, like when network breaks or a wrong passcode is submitted.

Which easing function should you use?

Ease? Ease in? Ease out? Ease in and out? Some cubic bezier curve?

The right easing adheres to the laws of physics. Disney’s principles of animation is the gold standard when it comes to that.

For enter animations, use bounce effect if you want immediate attention of the user, otherwise use a smooth acceleration (and deceleration, for that matter) that is incremental rather than linear. Bouncing should reflect gravity. Brandon Gregory’s post on natural-feeling animations provides all kinds of examples that fall in line with the laws of physics.

You can refer to this Gist by Adam Argyle for defining easings in CSS.

Lights, camera, and… intentional action!

Attention to detail is what separates outstanding animations from ordinary (or even straight up broken) ones. If you’re in the process of learning web animations or currently working on a project that calls for them, I sure hope this post can serve as a set of useful ground rules to help you get the most out of your work.

Apart from the rules, I’d also mention that good animations take time and practice. Sure, a lot of the stuff I covered here is somewhat anecdotal and based on personal experience, but that’s the result of developing an eye for animations after years of working with them. Learn, try, improve, and keep learning. Otherwise, you may end up with a collection of animations that deliver poor user experiences and even hurt the accessibility of your site.

The post Ground Rules for Web Animations appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.