Sometimes our sites need a little sprinkling of content management. Not always. Not a lot. But a bit. The CMS market is thriving with affordable, approachable products, so we’re not short of options. Thankfully, it is a very different world to the one that used to force companies to splash out a ga-jillionty-one dollars (not an exact cost: I rounded to the nearest bazillion) for an all-singing, all-dancing, all-integrating, all-personalizing, big-enterprise-certified™ CMS platform.

Sometimes, though, it’s nice to use a really simple tool that anyone updating content on the site is already familiar with, rather than getting to grips with a new CMS.

I like Trello a lot for managing ideas and tasks. And it has an API. Why not use it as a content source for a web site? I mean, hey, if we can do it with Google Sheets, then what’s to stop us from trying other things?

Hello, Trello

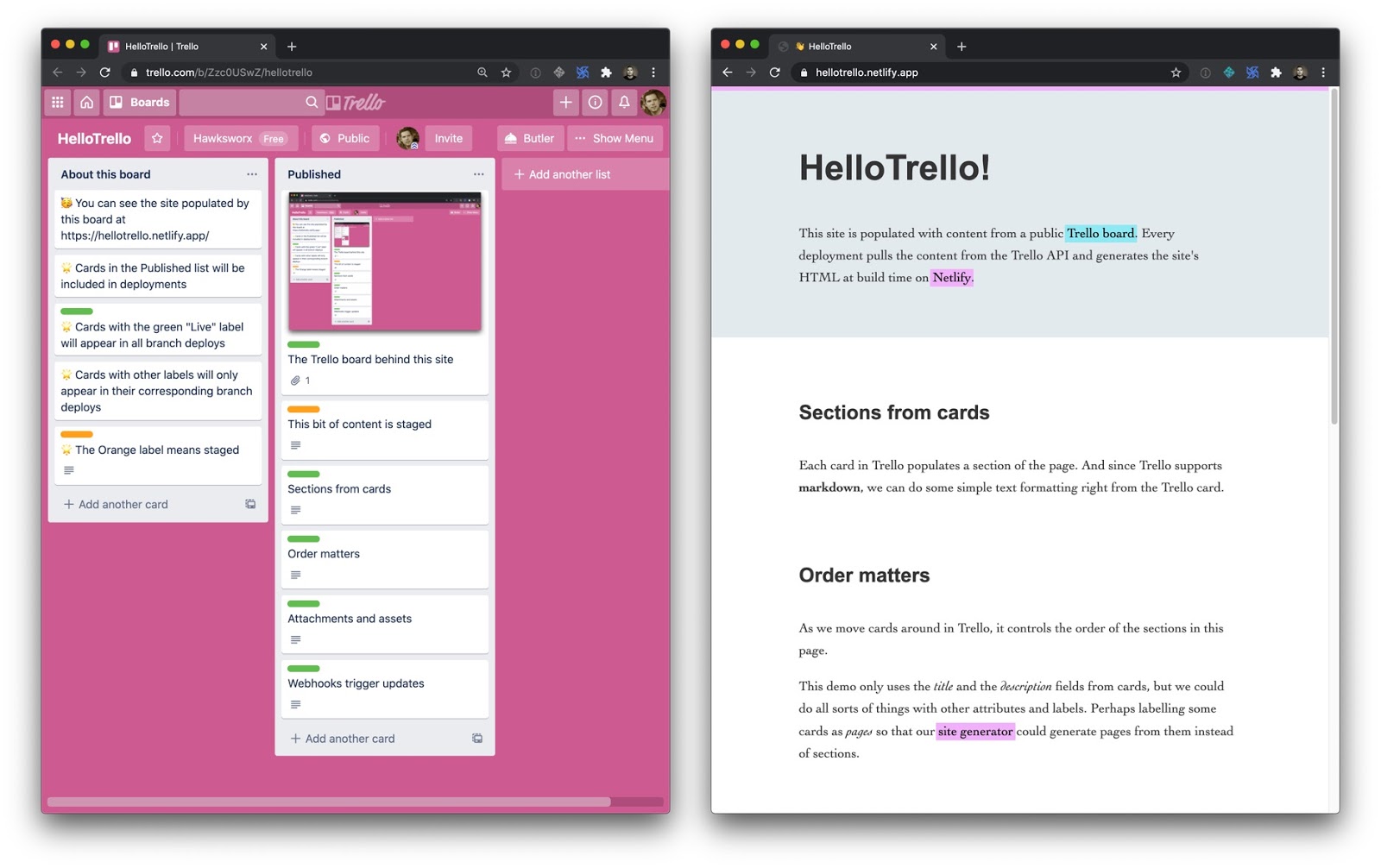

Here’s a simple site to explore. It gets its content from this Trello board and that content is displayed in sections. Each section is populated by the title and description fields of a card in our Trello board.

Trello uses Markdown, which comes in handy here. Anyone editing content in a Trello card is able to apply basic text formatting and have the same Markdown flow into the site and transformed into HTML by a build process.

Building blocks

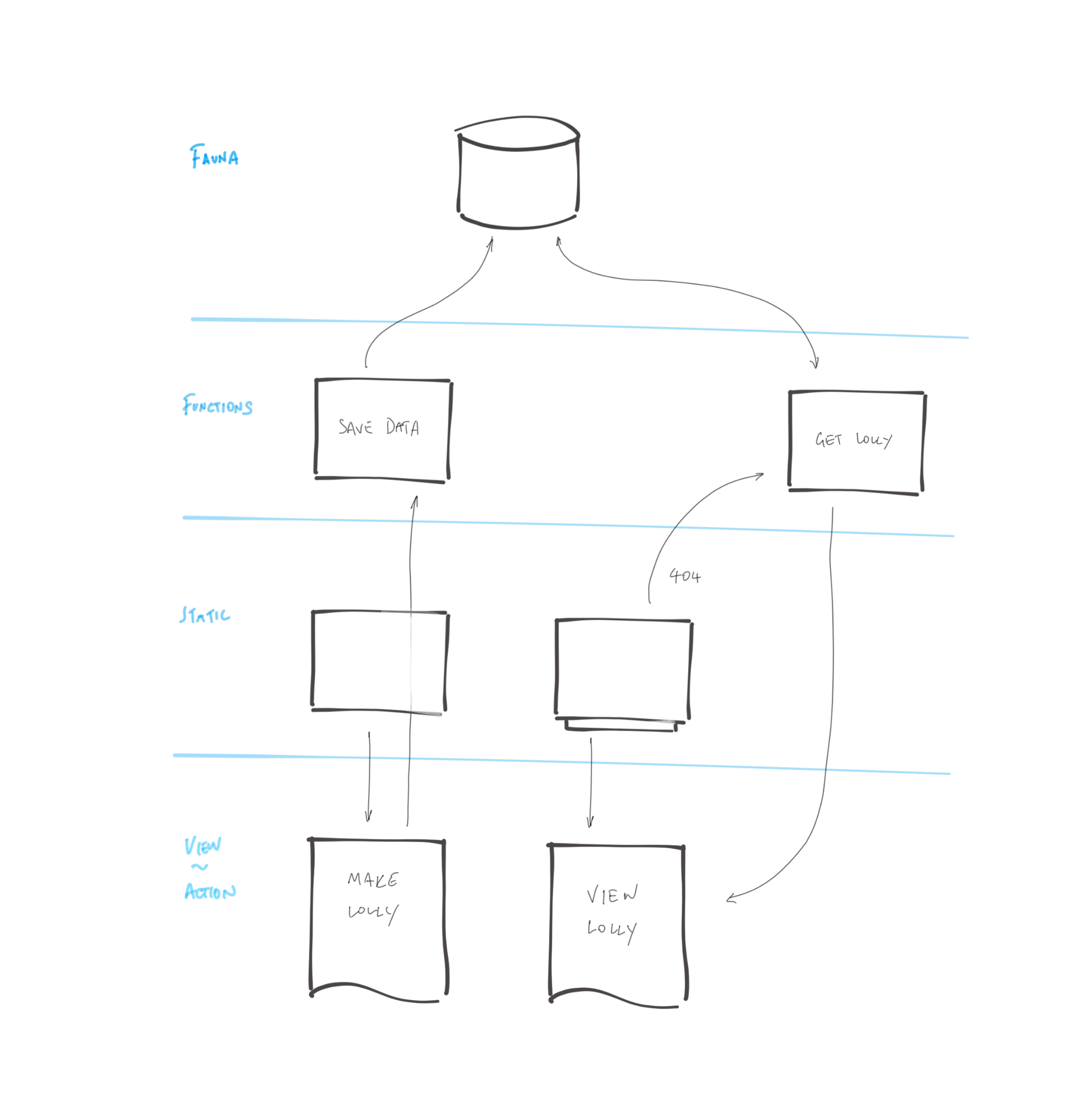

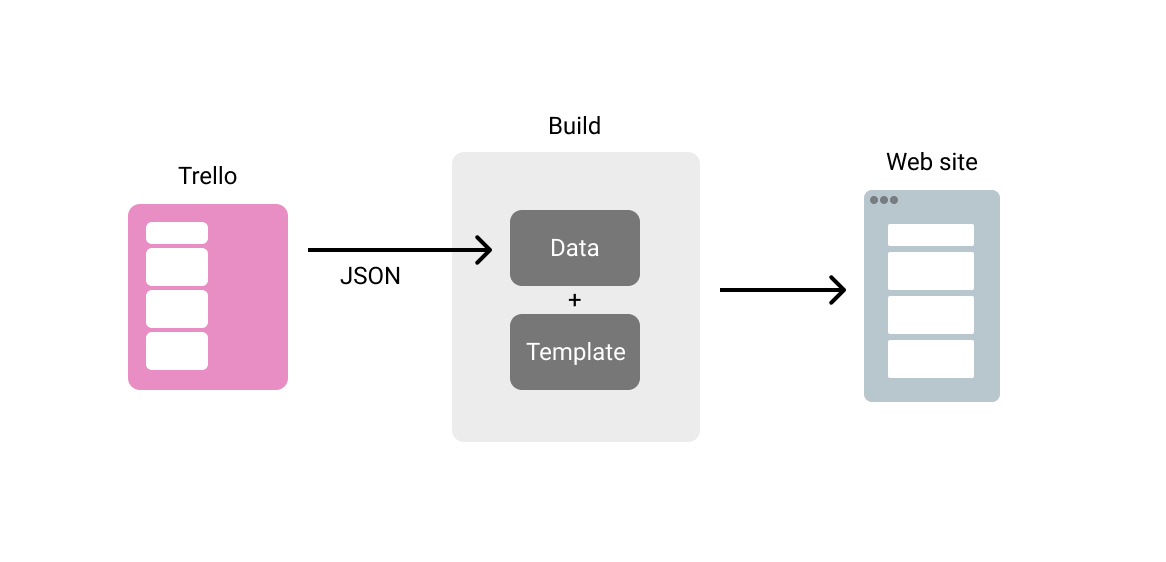

I’m a big fan of this model of running a build which pulls content from various feeds and sources, and then mashes them together with a template to generate the HTML of a website. It decouples the presentation from the management of the content (which is where the term “decoupled” comes from in popular modern CMS products). And it means that we are free to craft the website just the way we want with all of the wizzy tricks and techniques we’ve learned here on CSS-Tricks.

Since we pull in the content at build time, we don’t need to worry about the usage quotas or the performance of our data sources if our sites get popular and bring in loads of traffic. And why wouldn’t they? Look how pretty we made them!

I wanna play!

Fine. You can grab a copy of this site’s code and tinker around to your heart’s content. This version includes information on how to create your own Trello board and use it as the source for content for the build.

If you want to walk through how this works first rather than diving right into it yourself, read on.

Discovering the API

Trello has a well-documented API and set of developer resources. There is also a handy Node module to simplify the task of authenticating and interacting with the API. But you can also explore the API by tinkering with the URLs when you are exploring your Trello boards.

For example, the URL for the Trello board above is:

https://trello.com/b/Zzc0USwZ/hellotrelloIf we add .json to that URL, Trello shows us the content represented as JSON. Take a look.

We can use this technique to inspect the underlying data throughout Trello. Here is the URL for one card in particular:

https://trello.com/c/YVxlSEzy/4-sections-from-cardsIf we use this little trick and add .json to the URL we’ll see the data which describes that card.

We’ll find interesting things — unique IDs for the board, the list, and the card. We can see the card’s content, and lots of metadata.

I love doing this! Look at all the lovely data! How shall we use it?

Deciding how to use a board

For this example, let’s assume that we have a site with just one page of manageable content. A list or column in our board would be ideal for controlling the sections on that page. An editor could give them titles and content, and drag them around into the order they want.

We’ll need the ID of the list so that we can access it via the API. Luckily, we’ve already seen how to discover that — take a look at the data for any of the cards in the list in question. Each one has an idBoard property. Bingo!

Generating the site

The plan is to fetch the data from Trello and apply it to some templates to populate our site. Most static site generators (SSG) would do the job. That’s what they are good at. I’ll use Eleventy because I think it has the simplest concepts to understand. Plus, it is very efficient at getting data and generating clean HTML with Nunjucks (a popular templating language).

We’ll want to be able to use an expression lin our template that outputs a section element for each item found in a JavaScript object called trello:

<!-- index.njk -->

{% for card in trello %}

<section>

<h2>{{ card.name }}</h2>

<div>

{% markdown %}

{{- card.desc | safe }}

{% endmarkdown %}

</div>

</section>

{% endfor %}Fetching the data for the build

A popular technique with Jamstack sites like this is to run a build with Gulp, Grunt or [insert latest new build script hotness here] which goes and fetches data from various APIs and feeds, stashes the data in a suitable format for the SSG, and then runs the SSG to generate the HTML. This works rather nicely.

Eleventy simplifies things here by supporting the execution of JavaScript in its data files. In other words, rather than only leveraging data stored as JSON or YAML, it can use whatever gets returned by JavaScript, opening the door to making requests directly to APIs when the Eleventy build runs. We won’t need a separate build step to go off to fetch data first. Eleventy will do it for us.

Let’s use that to get the data for our trello object in the templates.

We could use the Trello Node client to query the API, but as it turns out all the data we want is right there in the JSON for the board. Everything! In one request! We can just fetch it in one go!

// trello.js

module.exports = () => {

const TRELLO_JSON_URL='https://trello.com/b/Zzc0USwZ/hellotrello.json';

// Use node-fetch to get the JSON data about this board

const fetch = require('node-fetch');

return fetch(TRELLO_JSON_URL)

.then(res => res.json())

.then(json => console.log(json));

};However, we don’t want to show all the data from that board. It includes cards on other lists, cards which have been closed and deleted, and so on. But we can filter the cards to only include the ones of interest thanks to JavaScript’s filter method.

// trello.js

module.exports = () => {

const TRELLO_JSON_URL='https://trello.com/b/Zzc0USwZ/hellotrello.json'

const TRELLO_LIST_ID='5e98325d6d6bd120f2b7395f',

// Use node-fetch to get the JSON data about this board

const fetch = require('node-fetch');

return fetch(TRELLO_JSON_URL)

.then(res => res.json())

.then(json => {

// Just focus on the cards which are in the list we want

// and do not have a closed status

let contentCards = json.cards.filter(card => {

return card.idList == TRELLO_LIST_ID && !card.closed;

});

return contentCards;

});

};That’ll do it! With this saved in a file called trello.js in Eleventy’s data directory, we’ll have this data ready to use in our templates in an object called trello.

Done-zo! 🎉

But we can do better. Let’s also handle attached images, and also add a way to have content staged for review before it goes live.

Image attachments

It’s possible to attach files to cards in Trello. When you attach an image, it shows up right there in the card with the source URL of the asset described in the data. We can make use of that!

If a card has an image attachment, we’ll want to get its source URL, and add it as an image tag to what our template inserts into the page at build time. That means adding the Markdown for an image to the Markdown in the description property of our JSON (card.desc).

Then we can let Eleventy turn that into HTML for us along with everything else. This code looks for cards in our JSON and massages the data into the shape that we’ll need.

// trello.js

// If a card has an attachment, add it as an image

// in the description markdown

contentCards.forEach(card => {

if(card.attachments.length) {

card.desc = card.desc + `\n`;

}

});Now we can move images around in our content too. Handy!

Staging content

Let’s add one more flourish to how we can use Trello to manage our site’s content.

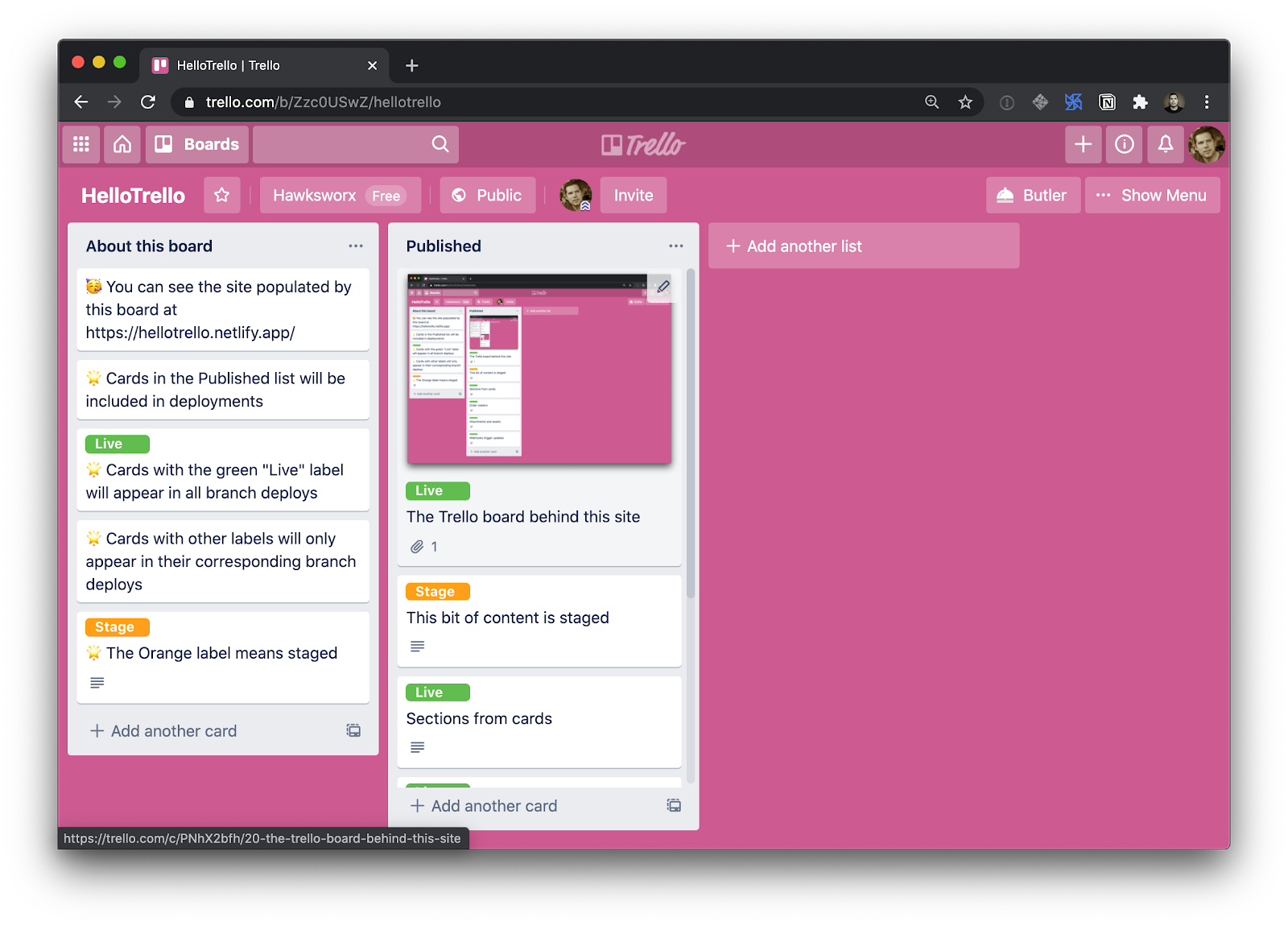

There are a few ways that we might want to preview content before launching it to the world. Our Trello board could have one list for staging and one list for production content. But that would make it hard to visualize how new content lives alongside that which is already published.

A better idea would be to use Trello’s labels to signify which cards are published live, and which should only be included on a staged version of the site. This will give us a nice workflow. We can add more content by adding a new card in the right place. Label it with “stage” and filter it out from the cards appearing on our production branch.

A little more filtering of our JavaScript object is called for:

// trello.js

// only include cards labelled with "live" or with

// the name of the branch we are in

contentCards = contentCards.filter(card => {

return card.labels.filter(label => (

label.name.toLowerCase() == 'live' ||

label.name.toLowerCase() == BRANCH

)).length;

});We want the content labelled ‘live’ to show up on every version of the build, staging or not. In addition we’ll look to include cards which have a label matching a variable called “BRANCH”.

How come? What’s that?

This is where we get crafty! I’ve chosen to host this site on Netlify (disclaimer: I work there). This means that I can run the build from Netlify’s CI/CD environment. This redeploys the site whenever I push changes to its git repository, and also gives access to a couple of other things which are really handy for this site.

One is Branch deploys. If you want a new environment for a site, you can create one by making a new branch in the Git repository. The build will run in that context, and your site will be published on a subdomain which includes the branch name. Like this.

Take a look and you’ll see all the cards from our list, including the one which has the orange “stage” label. We included it in this build because its label matched the branch name for the build context. BRANCH was an environment variable which contained whichever branch the build ran in.

label.name.toLowerCase() == BRANCHIn theory, we could make as many branches and labels as we like, and have all sorts of staging and testing environments. Ready to promote something from “stage” to “live”? Swap the labels and you’re good to go!

But how does it update though?

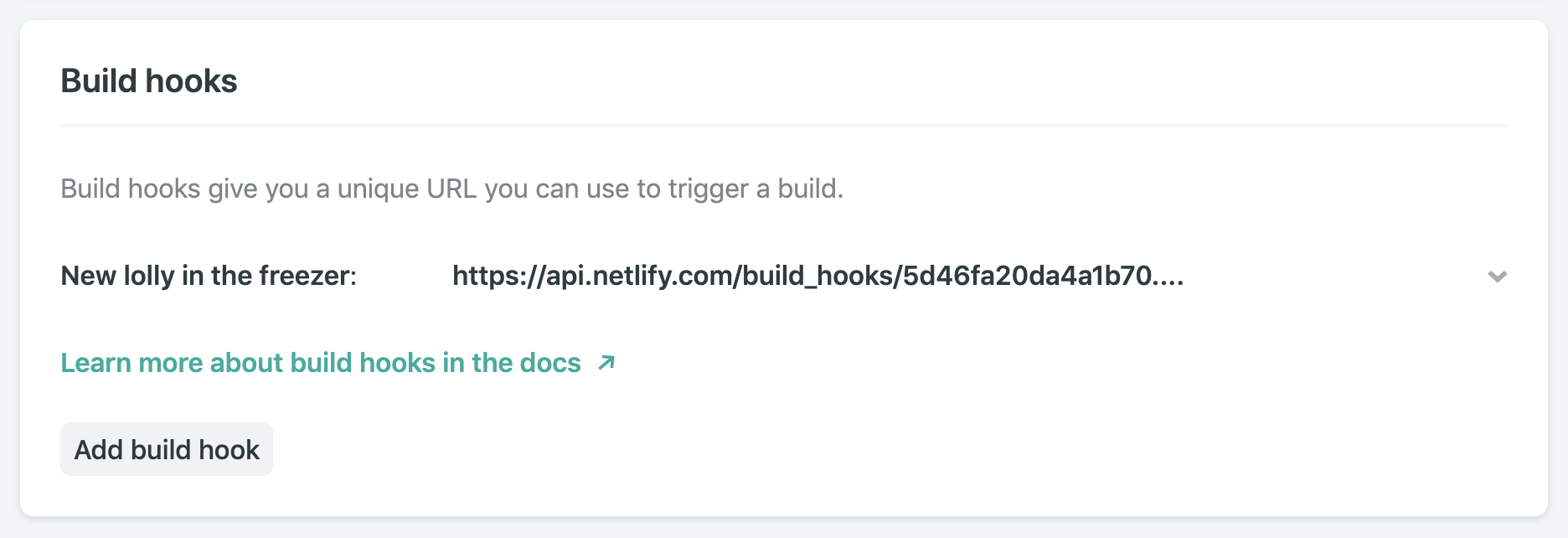

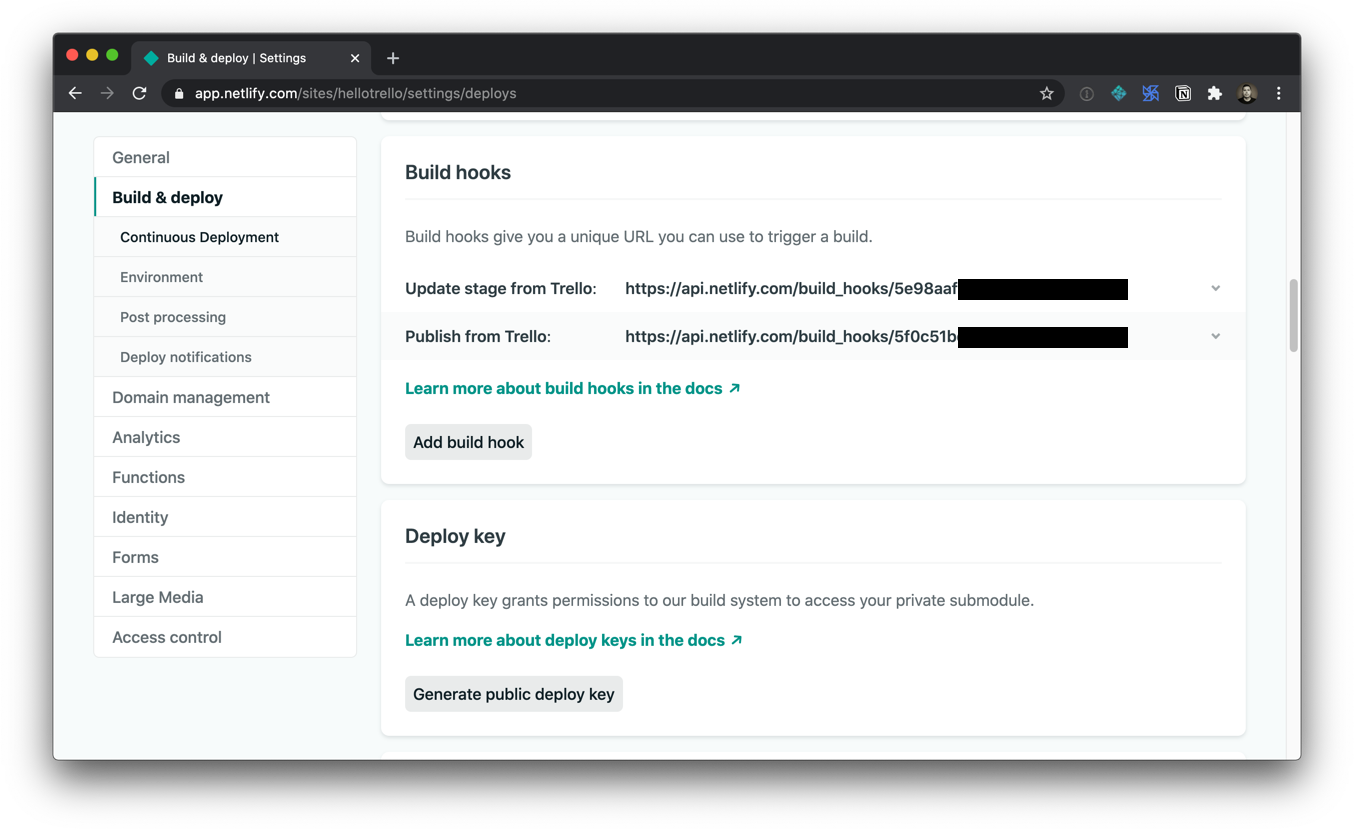

The second perk we get from running the site build in a CI/CD such as Netlify’s is that we can trigger a build to run whenever we like. Netlify lets us create build hooks. These are webhooks which initiate a new deployment when you send an HTTP POST to them.

If Trello supports webhooks too, then we could stitch these services together and refresh the site automatically whenever the Trello board changes. And guess what… they do! Hoorah!

To create a Netlify build hook, you’ll need to visit your site’s admin panel. (You can bootstrap this demo site into a new Netlify site in a couple of clicks if you want to try it out.)

Now, armed with a new build hook URL, we’ll need to register a new Trello webhook which calls it when content changes. The method for creating webhooks in Trello is via Trello’s API.

The repo for this site includes a little utility to call the Trello API and create the webhook for you. But you’ll need to have a Trello developer token and key. Thankfully, it is easy to create those for free by visiting the Trello Developer portal and following the instructions under “Authorizing a client.”

Got ‘em? Great! If you save them in a .env file in your project, you can run this command to set up the Trello webhook:

npm run hook --url https://api.netlify.com/build_hooks/XXXXXAnd with that, we’ve created a nice little flow for managing content on a simple site. We can craft our frontend just the way we want it, and have updates to the content happen on a Trello board which automatically updates the site whenever changes are made.

Could I really use this though?

This is a simplistic example. That’s by design. I really wanted to demonstrate the concepts of decoupling, and of using the API of an external service to drive the content for a site.

This won’t replace a full-featured decoupled CMS for more involved projects. But the principles are totally applicable to more complex sites.

This model, however, could be a great match for the types of websites we see for businesses such as independent shops, bars and restaurants. Imagine a Trello board that has one list for managing a restaurant’s home page, and one for managing their menu items. Very approachable for the restaurant staff to manage, and far nicer than uploading a new PDF of the menu whenever it changes.

Ready to explore an example and experiment with your own board and content? Try this:

- Clone and deploy the example from above, and start making your changes.

- Learn more about Netlify what you can do with Netlify branch builds

- Dig deeper into the Trello developer resources.

The post Using Trello as a Super Simple CMS appeared first on CSS-Tricks.

You can support CSS-Tricks by being an MVP Supporter.