Markdown is second nature for many of us. Looking back, I remember starting typing in Markdown not long after John Gruber released his first Perl-based parser back in 2004 after collaborating on the language with Aaron Swartz.

Markdown’s syntax is intended for one purpose: to be used as a format for writing for the web.

— John Gruber

That’s almost 20 years ago — yikes! What started as a more writer- and reader-friendly syntax for HTML has become a darling for how to write and store technical prose for programmers and tech-savvy people.

Markdown is a signifier for the developer and text-tinkerer culture. But since its introduction, the world of digital content has also changed. While Markdown is still fine for some things, I don’t believe it’s should be the go-to for content anymore.

There are two main reasons for this:

- Markdown wasn’t designed to meet today’s needs of content.

- Markdown holds editorial experience back.

Of course, this stance is influenced by working for a platform for structured content. At Sanity.io, we spend most of our days thinking about how content as data unlocks a lot of value, and we spend a lot of time thinking deeply about editor experiences, and how to save people time, and make working with digital content delightful. So, there’s skin in the game, but I hope I’m able to portray that even though I’ll argue against Markdown as the go-to format for content, I still have a deep appreciation for its significance, application, and legacy.

Before my current gig, I worked as a technology consultant at an agency where we had to literally fight CMSes that locked our client’s content down by embedding it in presentation and complex data models (yes, even the open-source ones). I have observed people struggle with Markdown syntax, and be demotivated in their jobs as editors and content creators. We have spent hours (and client’s money) on building custom tag-renderers that were never used because people don’t have time or motivation to use the syntax. Even I, when highly motivated, have given up contributing to open-source documentation because the component-based Markdown implementation introduced too much friction.

But I also see the other side of the coin. Markdown comes with an impressive ecosystem and from a developer’s standpoint, there is an elegant simplicity to plain-text files and easy-to-parse syntax for people who are used to reading code. I once spent days building an impressive MultiMarkdown->LaTeX->real-time-PDF-preview-pipeline in Sublime Text for my academic writing. And it makes sense that a README.md file can be opened and edited in a code editor and rendered nicely on GitHub. There’s little doubt that Markdown brings convenience for developers in some use cases.

That is also why I want to build my advice against Markdown by looking back on why it was introduced in the first place, and by going through some of the major developments of content on the web. For many of us, I suspect Markdown is something we just take for granted as a “thing that exists.” But all technology has a history and is a product of human interaction. This is important to remember when you, the reader, develop technology for others to use.

Flavors And SpecificationsMarkdown was designed to make it easier for web writers to work with articles in an age where web publishing required writing HTML. So, the intent was to make it simpler to interface with text formatting in HTML. It wasn’t the first simplified syntax on the planet, but it was the one that gained the most traction over the years. Today, the usage of Markdown has grown far beyond its design intent to be a simpler way to read and write HTML, to become an approach of marking up plain text in a lot of different contexts. Sure, technologies and ideas can evolve beyond their intent, but the tension in today’s use of Markdown can be traced to this origin and the constraints put into its design.

For those who aren’t familiar with the syntax, take the following HTML content:

<p>The <a href=”https://daringfireball.net/projects/markdown/syntax#philosophy”>Markdown syntax</a> is designed to be <em>easy-to-read</em> and <em>easy-to.write</em>.</p>With Markdown, you can express the same formatting as:

The Markdown syntax is designed to be _easy-to-read_ and _easy-to-write_.It’s like a law of nature that technology adoption comes with the pressure to evolve and add features to it. Markdown’s increasing popularity meant that people wanted to adapt it for their use cases. They wanted more features like support for footnotes and tables. The original implementation came with an opinionated stance, which at the time were reasonable for what the design intent was:

For any markup that is not covered by Markdown’s syntax, you simply use HTML itself. There’s no need to preface it or delimit it to indicate that you’re switching from Markdown to HTML; you just use the tags.

— John Gruber

In other words, if you want a table, then use <table></table>. You’ll find that this is still the case for the original implementation. One of Markdown’s spiritual successors, MDX, has taken the same principle but extended it to JSX, a JS-based templating language.

From Markdown To Markdown?

It can look like Markdown’s appeal for many wasn’t so much its tie-in to HTML, but the ergonomics of plaintext and simple syntax for formatting. Some content creators wanted to use Markdown for other use cases than simple articles on the web. Implementations like MultiMarkdown introduced affordances for academic writers who wanted to use plain text files but needed more features. Soon you would have a range of writing apps that accepted Markdown syntax, without necessarily turning it into HTML or even using the markdown syntax as a storage format.

In a lot of apps, you’ll find editors that give you a limited set of formatting options, and some of them are more “inspired” by the original syntax. In fact, one of the feedbacks I got on a draft of this article was that by now, “Markdown” should be lower-cased, since it has become so common, and to make it distinct from the original implementation. Because what we recognize as markdown has also become very diverse.

CommonMark: An Attempt To Tame Markdown

Like ice cream, Markdown comes in a lot of flavors, some more popular than others. When people started to fork the original implementation and add features to it, two things happened:

- It became more unpredictable what you as a writer could and couldn’t do with Markdown.

- Software developers had to make decisions of what implementation to adopt for their software. The original implementation also contained some inconsistencies that added friction for people who wanted to use it programmatically.

This started conversations about formalizing Markdown into a specification proper. Something that Gruber resisted, and still does, interestingly, because he recognized that people wanted to use Markdown for different purposes and “No one syntax would make all happy.” It’s an interesting stance considering that Markdown translates to HTML, which is a specification that evolves to accommodate different needs.

Even though the original implementation of Markdown is covered by a “BSD-like” license, it also reads “Neither the name Markdown nor the names of its contributors may be used to endorse or promote products derived from this software without specific prior written permission.” We can safely assume that most products that use “Markdown” as part of their marketing materials haven’t acquired this written permission.

The most successful attempt to bring Markdown into a shared specification is what is today known as CommonMark. It was headed by Jeff Atwood (known for co-founding Stack Overflow and Discourse) and John McFarlane (a professor of philosophy at Berkely who’s behind Babelmark and pandoc). They initially launched it as “Standard Markdown,” but changed it to “CommonMark” after receiving criticism from Gruber. Whose stance was consistent, the intent of Markdown is to be a simple authoring syntax that translates to HTML:

@davewiner And that’s what’s flawed with CommonMark. They want to make things easier for programmers as a primary goal. They miss the point.

— John Gruber (@gruber) September 8, 2014

I think this also marked the point where Markdown had entered the public domain. Even though CommonMark isn’t branded as “Markdown,” (as per licensing) this specification is recognized and referred to as “markdown”. Today, you’ll find CommonMark as the underlying implementation for software like Discourse, GitHub, GitLab, Reddit, Qt, Stack Overflow, and Swift. Projects like unified.js bridges syntaxes by translating them into Abstract Syntax Trees, also rely on CommonMark for their markdown support.

CommonMark has brought a lot of unification around how markdown is implemented, and in a lot of ways has made it simpler for programmers to integrate markdown support in software. But it hasn’t brought the same unification to how markdown is written and used. Take GitHub Flavored Markdown (GFM). It’s based on CommonMark but extends it with more features (like tables, task lists, and strikethrough). Reddit describes its “Reddit Flavored Markdown” as “a variation of GFM,” and introduces features like syntax for marking up spoilers. I think we can safely conclude that both the group behind CommonMark and Gruber were right: it certainly helps with shared specifications, but yes, people want to use Markdown for different specific things.

Markdown As A Formatting Shortcut

Gruber resisted formalizing Markdown into a shared specification because he assumed it would make it less a tool for writers and more a tool for programmers. We have already seen that even with the broad adoption of a specification, we don’t automatically get a syntax that predictably works the same across different contexts. And specifications like CommonMark, popular as it is, also have limited success. An obvious example is Slack’s markdown implementation (called mrkdown) that translates *this* to strong/bold, and not emphasis/italic, and doesn’t support the [link](https://slack.com) syntax, but uses <link|https://slack.com> instead.

You’ll also find that you can use Markdown-like syntax to initialize formatting in rich text editors in software like Notion, Dropbox Paper, Craft, and to a degree, Google Docs (e.g. asterisk + space on a new line will transform to a bulleted list). What’s supported and what’s translated to what varies. So, you can’t necessarily take your muscle memory with you across these applications. For some people, this is fine, and they can adapt. For others, this is a papercut and it keeps them from using these features. Which asks the question, who was Markdown designed for, and who are its users today?

We have seen markdown exist in a tension between different use cases, audiences, and notions of whom its users are. What started as a markup language for HTML-proficient web writers specifically, became a darling for developer types.

In 2014, web writers started to move away from moving files through parsers in Perl and FTP. Content Management Systems (CMSs) like WordPress, Drupal, and Moveable Type (which I believe Gruber still uses) had steadily grown to become the go-to tools for web publishing. They offered affordances like rich text editors that web writers could use in their browsers.

These rich text editors still assumed HTML and Markdown as the underlying rich text syntax, but they took away some of the cognitive overhead by adding buttons to insert this syntax in the editor. And increasingly, writers weren’t and didn’t have to be versed in HTML. I bet if you did web development with CMSs in the 2010s, you probably had to deal with “junk HTML” that came through these editors when people pasted directly from Word.

Today, I will argue that Markdown’s primary users are developers and people who are interested in code. It’s not a coincidence that Slack made the WYSIWYG the default input mode once their software was used by more people outside of technical departments. And the fact that this was a controversial decision, so much that they had to bring it back as an option, shows how deep the love for markdown is in the developer community. There wasn’t much celebration of Slack trying to make it easier and more accessible for everyone. And this is the crux of the matter.

The fact that markdown has become the lingua franca writing style, and what most website frameworks cater to, is also the main reason I’ve been a bit skittish about publishing this. It’s often talked about as an inherent and undeniable good. Markdown has become a hallmark of being developer-friendly. Smart and skilled people have sunk a lot of collective hours in enabling markdown in all sorts of contexts. So, challenging its hegemony will surely annoy some. But hopefully, it can spawn some fruitful discussion about a thing that’s often taken for granted.

My impression is that the developer friendliness that people relate to Markdown has mostly to do with 3 factors:

- The comfortable abstraction of a plain text file.

- There is an ecosystem of tooling.

- You can keep your content close to your development workflow.

I’m not saying that these stances are wrong, but I’ll suggest that they come with trade-offs and some unreasonable assumptions.

The Simple Mental Model Of A Plain Text File

Databases are amazing things. But they have also had an earned reputation of being hard and inaccessible for frontend developers. I’ve known a lot of great developers who shy away from backend code and databases, because they represent complexity they don’t want to spend time on. Even with WordPress, which does a lot out of the box to keep you from having to deal with its database after setup, it was overhead of getting up and running.

Plain text files, however, are more tangible and are fairly simple to reason about (as long as you’re used to file management that is). Especially compared to a system that will break your content into multiple tables in a relational database with some proprietary structure. For limited use cases, like blog posts of simple rich text with images and links, markdown will get the job done. You can copy the file and stick it in a folder or check it into git. The content feels yours because of the tangibility of files. Even if they’re hosted on GitHub, which is a for-profit Software as a Service owned by Microsoft, and thus covered by their terms of service.

In the era where you actually had to spin up a local database to get your local development going and deal with syncing it with remote, the appeal of plain text files is understandable. But that era is pretty much gone with the emergence of backends as a service. Services and tools like Fauna, Firestore, Hasura, Prisma, PlanetScale, and Sanity’s Content Lake, invest heavily in developer experience. Even operating traditional databases on local development has become less of a hassle compared to just 10 years ago.

If you think about it, do you own your content less if it’s hosted in a database? And hasn’t the developer experience of dealing with databases become significantly simpler with the advent of SaaS tools? And is it fair to say that proprietary database technology impinges on the portability of your content? Today you can launch what’s essentially a Postgres database with no sysadmin skills, make your tables and columns, put your content inside of it, and at any time export it as a .sql dump.

The portability of content has much more to do with how you structure that content in the first place. Take WordPress, it’s fully open-source, you can host your own DB. It even has a standardized export format in XML. But anyone who has tried to move out of a mature WordPress install knows how little this helps if you’re trying to get away from WordPress.

A Vast Ecosystem… For Developers

We already touched on the vast markdown ecosystem. If you look at contemporary website frameworks, most of them assume markdown as a primary content format, some of them, the only format. For example, Hugo, the static site generator used by Smashing Magazine, still requires markdown files for paginated publishing. Meaning that if Smashing Magazine wants to use a CMS to store articles, it has to interact with markdown files, or convert all the content to markdown files. If you look in the documentation for Next.js, Nuxt.js, VuePress, Gatsby.js, and so on, markdown will figure prominently. It’s also the default syntax for README-files on GitHub, which also uses it for formatting in Pull Request notes and comments.

There are some honorable mentions of initiatives to bring the ergonomics of markdown to the masses. Netlify CMS and TinaCMS (the spiritual descendant of Forestry) will give you user interfaces where the markdown syntax is mostly abstracted away for editors. You will commonly find that markdown-based editors in CMSes give you preview functionality for the formatting. Some editors, like Notion’s, will let you paste markdown syntax, and they will translate it to their native formatting. But I think it’s safe to say, that the energy that has gone to innovate for markdown hasn’t favored people who aren’t into writing its syntax. It hasn’t trickled up the stack, as it were.

Content Workflows Or Developer Workflows?

For a developer who makes their blog, using markdown files reduces some of the overhead of getting it up and running, since frameworks often come with built-in parsing or commonly offer it as part of starter code. And there is nothing extra to sign up for. You can use git to commit these files alongside your code. If you are comfortable with git diffs, you’ll even have revision control like you’re used to with programming. In other words, since markdown files are in plain text, they can be integrated with your developer workflow.

But beyond this, the developer experience soon gets more complex. And you end up compromising on your team’s user experience as content creators, and our own developer experience being stuck with markdown to solve problems that are way beyond its design intent.

Yes, it might be cool if you get your content team to use git and check in their changes, but at the same time, is this the best use of their time? Do you really want your editors to bump against merge conflicts or how to rebase branches? Git is hard enough for developers who use it every day. And does this setup really represent the best workflow for people who are primarily working with content? Isn’t this a case where developer experience has trumped editor experience, and isn’t the cost, the time and effort that could go into making something better for users?

Because the expectations and needs from content and editing environments have evolved, I don’t think markdown will do it for us. I don’t see how some of the developer ergonomics end up favoring non-developers, and I think even for developers, markdown is holding our own content creation and needs back. Because content on the web has significantly changed since the early 2000s.

From Paragraphs To BlocksMarkdown has always had the option of opting out to HTML if you wanted more complex things. This worked well when the author was also the webmaster, or at least knew HTML. It also worked well because websites usually were mostly HTML and CSS. The way you designed websites was mostly by creating whole page layouts. You could transform Markdown to the HTML markup and put it up alongside your style.css file. Of course, we had CMSes and static site generators in the 2000s too, but they mostly worked the same, by inserting the HTML content inside of templates without any passing of “props” between the components.

But most of us don’t really author HTML like in the old days anymore. Content on the web has evolved from mostly being articles with simple rich text formatting to composed multimedia and specialized components often with user interactivity (which is a fancy way of saying “newsletter signup call to actions”).

From Articles To Apps

In the early 2010s, Web 2.0 was in its heyday, and Software as a Service-companies began to use the web for data-heavy applications. HTML, CSS, and JavaScript were increasingly used to drive interactive UIs. Twitter open-sourced Bootstrap, their framework for building more consistent and resilient user interfaces. This drove what we can call the “componentization” of web design. It shifted the way we build for the web in a fundamental way.

The various CSS frameworks that emerged in this era (e.g. Bootstrap and Foundation) tended to use standardized class names and assumed specific HTML structures to make it less hard to make resilient and responsive user interfaces. With the web design philosophy of Atomic Design and class-name conventions like Block-Element-Modifier (BEM) the default was shifted from thinking page-layout first, to seeing pages as a collection of repeatable and compatible design elements.

Whatever content you have inside of markdown is not compatible with this. Unless you down the rabbit hole of interjecting the markdown parsers, and tweaked it to output the syntax you wanted (more on this later). No wonder, Markdown was designed to be simple rich text articles of native HTML elements that you would target with a stylesheet.

This is still an issue for people who use Markdown to drive content for their sites.

The Embeddable Web

But something also happened to our content as well. Not only could we start finding it outside of the semantic <article> HTML-tags, but it started to contain more… stuff. A lot of our content moved out from our LiveJournals and blogs and into social media: Facebook, Twitter, tumblr, YouTube. To get the snippets of content back into our articles, we needed to be able to embed them. The HTML convention started using the <iframe> tag to channel the video player from YouTube or even insert a tweet-box in between your paragraphs of text. Some systems started abstracting this into “short-codes”, most often brackets containing some keyword to identify what block of content it should represent, and some key-value attributes. For example, dev.to have enabled syntax from the templating language liquid to be inserted into their Markdown editor:

{% youtube dQw4w9WgXcQ %}Of course, this requires you to use a customized Markdown parser, and have special logic to make sure the right HTML was inserted when the syntax was turned into HTML. And your content creators will have to remember these codes (unless there was some kind of toolbar to automatically insert them). And if a bracket gets deleted or messed up, that might break the site.

But what about MDX?

An attempt to solve the need for block content is MDX, presented with the tagline “Markdown for the component era.” MDX lets you use the JSX templating language, as well as JavaScript, interlaced in markdown syntax. There is a lot of impressive engineering in the community around MDX, including Unified.js, which specializes in parsing various syntaxes into Abstract Syntax Trees (ASTs), so that they are more accessible to be used programmatically. Note, that the standardization of markdown would make the work for the folks behind Unified.js and its users simpler, because there are fewer edge cases to cater for.

MDX certainly brings better developer experience in integrating components into Markdown. But it doesn’t bring better editor experience, because it adds a lot of cognitive overhead to content production and editing:

import {Chart} from './snowfall.js'

export const year = 2018

# Last year’s snowfall

In {year}, the snowfall was above average.

It was followed by a warm spring which caused

flood conditions in many of the nearby rivers.

<Chart year={year} color="#fcb32c" />The amount of assumed knowledge just for this simple example is substantial. You need to know about ES6 modules, JavaScript variables, JSX templating syntax, and how to use props, hex codes, and data types, and you need to be familiar with what components you can use, and how to use them. And you need to type it correctly and in an environment that gives you some kind of feedback. I have no doubt that there will be more accessible authoring tools on top of MDX, it feels like solving for something that doesn’t need to be a problem in the first place.

Unless you are extremely diligent in how you compose and name your MDX components, it also ties your content to a specific presentation. Just take the example above brought from the MDX front page. You’ll find a hard-coded color hex for the chart. When you redesign your site, that color might not be compatible with your new design system. Of course, there’s nothing keeping you from abstracting this and using the prop color=”primary”, but there’s also nothing in the tool that nudges you to make wise decisions like this.

Embedding specific presentation concerns in your content has increasingly become a liability and something that will get in the way of adapting, iterating, and moving quickly with your content. It locks it down in ways that are much more subtle than having content in a database. You risk ending up in the same place as moving out of a mature WordPress install with plugins. It is cumbersome to unmix structure and presentation.

The Demand For Structured Content

With more complex sites and user journeys, we also see the need to present the same pieces of content throughout a website. If you’re running an e-commerce site, you want to embed product information in many places outside a single product page. If you run a modern marketing site, you want to be able to share the same copy across multiple personalized views.

To do this efficiently and reliable you will need to adapt structured content. That means your content needs to be embedded with metadata and chunked up in ways that make it possible to parse for intent. If a developer just sees “page” with “content,” that makes it very difficult to include the right things in the right places. If they can get to all “product descriptions” with an API or a query, that makes everything easier.

With markdown, you’re limited to expressing taxonomies and structured content either to some sort of folder organization (making it hard to put the same piece of content in multiple taxonomies) or you need to augment the syntax with something else.

Jekyll, an early Static Site Generator (SSG) built for markdown files, introduced “Front Matter” as a way to add metadata to posts using YAML (a simple key-value format that uses spaces to create scope) between three dashes at the top of the file. So, now you’ll have two syntaxes to deal with. YAML also has a reputation for being mischievous (especially if you’re from Norway). Nevertheless, other SSGs have adopted this convention, as well as git-based CMSes that use markdown as their content format.

When you have to add additional syntax to your plain files to get some of the affordances of structured content, you may start to wonder if it’s really worth it. And who the format is for and who it excludes.

If you think about it, a lot of what we do on the web is not only consuming content, we’re creating it! I’m currently writing this lengthy article in an advanced word processor in my browser.

There’s a growing expectation that you should also be able to author block content in modern content applications. People have started to get used to delightful user experiences that works and looks nice, and where you aren’t expected to have to learn specialized syntax. Medium popularized the notion that you could have delightful and intuitive content creation on the web. And speaking of “notion”, the popular note app has gone all in on block content, and lets users mix max from a wide range of different types. Most of these blocks goes beyond markdown, and the native elements of HTML.

It’s notable that Notion, describing their process to make their content accessible through their highly anticipated API, makes a point out of chosing their content format, that:

Documents from one Markdown editor will often parse and render differently in another application. The inconsistency tends to be manageable for simple documents, but it's a big problem for Notion's rich library of blocks and inline formatting options, many of which are simply not supported in any widely-used Markdown implementation.

Notion went with a JSON based format that let them express as structured data. Their argument is that it makes it easier and more predictable to interact with for developers who want to build their own presentation of the block content that comes out of Notion’s APIs.

If Not Markdown, Then What?I suspect that the prominence of Markdown has held back innovation and progress for digital content. So, when I argue that we should stop choosing it as a primary way to store content, it’s hard to give a straight answer to what should replace it. What we do know, however, is what we should expect from modern content formats and authoring tools.

Let’s Invest In Accessible Authoring Experiences

Using markdown requires you to learn syntax, and often multiple syntaxes and bespoke tags to be practical with modern expectations. Today, that feels like a completely unnecessary expectation to put on most people. I wish we could direct more energy into making accessible and delightful editorial experiences that produces modern portable content formats.

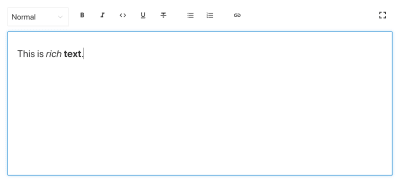

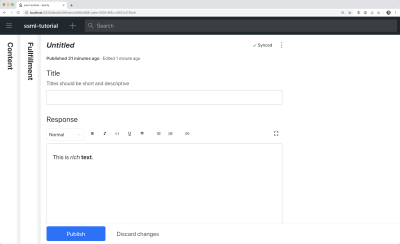

Even though it’s notoriously difficult to build great block content editors, there are a couple of viable options out there that can be extended and customized for your use case (for example Slate.js, Quill.js, or Prosemirror). Then again, investing in the communities around these tools might also help their development further.

Increasingly, people will expect authoring tools to be accessible, real-time, and collaborative. Why should one have to push a save button on the web in 2021? Why shouldn’t it be possible to make a change in a document without risking a race condition, because your colleague happened to have the document open in a tab? Should we expect authors to have to deal with merge conflicts? And shouldn’t we make it easy for content creators to work with structured content with visual affordances that make sense?

To be a bit polemical: the last decade’s innovations in reactive JavaScript frameworks and UI components are perfect for creating awesome authoring tools. Instead of using them to transpile Markdown to HTML and into an abstract syntax tree to then integrate it in a JavaScript template language that outputs HTML.

Block Content Should Follow A Specification

I haven’t mentioned WYSIWYG editors for HTML. Because they are the wrong thing. Modern block content editors should preferably interoperate with a specified format. The aforementioned editors do at least have a sensible internal document model that can be transformed into something more portable. If you look at the content management system landscape, you start to see various JSON-based block content formats emerge. Some of them are still tied to HTML assumptions or overly concerned with character positions. And none of them aren’t really offered as a generic specification.

At Sanity.io, we decided early that the block content format should never assume HTML as neither input nor output, and that we could use algorithms to synchronize text strings. More importantly, was it that block content and rich text should be deeply typed and queryable. The result was the open specification Portable Text. Its structure not only makes it flexible enough to accommodate custom data structures as blocks and inline spans; it’s also fully queryable with open-source query languages like GROQ.

Portable Text isn’t design to be written or be easily readable in its raw form; it’s designed to be produced by an user interface, manipulated by code, and to be serialized and rendered where ever it needs to go. For example, you can use it to express content for voice assistants.

{

"style": "normal",

"_type": "block",

"children": [

{

"_type": "span",

"marks": ["a-key", "emphasis"],

"text": "some text"

}

],

"markDefs": [

{

"_key": "a-key",

"_type": "markType",

"extraData": "some data"

}

]

}

An interesting side-effect of turning block content into structured data is exactly that: It becomes data! And data can be queried and processed. That can be highly useful and practical, and it lets you ask your content repository questions that would be otherwise harder and more errorprone in formats like Markdown.

For example, if I for some reason wanted to know what programming languages we’ve covered in examples on Sanity’s blog, that’s within reach with a short query. You can imagine how trivial it is to build specialized tools and views on top of this that can be helpful for content editors:

distinct(

*["code" in body[]._type]

.body[_type == "code"]

.language

)

// output

[

"text",

"javascript",

"json",

"html",

"markdown",

"sh",

"groq",

"jsx",

"bash",

"css",

"typescript",

"tsx",

"scss"

]Example: Get a distinct list of all programming languages that you have code blocks of.

Portable Text is also serializable, meaning that you can recursively loop through it, and make an API that exposes its nodes in callback functions mapped to block types, marked-up spans, and so on. We have spent the last years learning a lot about how it works and how it can be improved, and plan to take it to 1.0 in the near future. The next step is to offer an editor experience outside of Sanity Studio. As we have learned from Markdown, the design intent is important.

Of course, whatever the alternative to markdown is, it doesn’t need to be Portable Text, but it needs to be portable text. And it needs to share a lot of its characteristics. There have been a couple of other JSON-based block content format popping up the last few years, but a lot of them seem to bring with them a lot of “HTMLism.” The convenience is understandable, since a lot of content still ends up on the web serialized into HTML, but the convenience limits the portability and the potential for reuse.

You can disregard my short pitch for something we made at Sanity, as long as you embrace the idea of structured content and formats that let you move between systems in a fundamental manner. For example, a goal for Portable Text will be improved compatibility with Unified.js, so it’s easier to travel between formats.

Embracing The Legacy Of MarkdownMarkdown in all its flavors, interpretations, and forks won’t go away. I suspect that plain text files will always have a place in developers’ note apps, blogs, docs, and digital gardens. As a writer who has used markdown for almost two decades, I’ve become accustomed to “markdown shortcuts” that are available in many rich text editors and am frequently stumped from Google Docs’ lack of markdownisms. But I’m not sure if the next generation of content creators and even developers will be as bought in on markdown, and nor should they have to be.

I also think that markdown captured a culture of savvy tinkerers who love text, markup, and automation. I’d love to see that creative energy expand and move into collectively figuring out how we can make better and more accessible block content editors, and building out an ecosystem around specifications that can express block content that’s agnostic to HTML. Structured data formats for block content might not have the same plain text ergonomics, but they are highly “tinkerable” and open for a lot of creativity of expression and authoring.

If you are a developer, product owner, or a decision-maker, I really want you to be circumspect of how you want to store and format your content going forward. If you’re going for markdown, at least consider the following trade-offs:

Markdown is not great for the developer experience in modern stacks:

- It can be a hassle to parse and validate, even with great tooling.

- Even if you adopt CommonMark, you aren’t guaranteed compatibility with tooling or people’s expectations.

- It’s not great for structured content, YAML frontmatter only takes you so far.

Markdown is not great for editorial experience:

- Most content creators don’t want to learn syntax, their time is better spent on other things.

- Most markdown systems are brittle, especially when people get syntax wrong (which they will).

- It’s hard to accommodate great collaborative user experiences for block content on top of markdown.

Markdown is not great in block content age, and shouldn’t be forced into it. Block content needs to:

- Be untangled from HTMLisms and presentation agnostic.

- Accommodate structured content, so it can be easily used wherever it needs to be used.

- Have stable specification(s), so it’s possible to build on.

- Support real-time collaborative systems.

What’s common for people like me who challenge the prevalence of markdown, and those who are really into the simple way of expressing text formating is an appreciation of how we transcribe intent into code. That’s where I think we can all meet. But I do think it’s time to look at the landscape and the emerging content formats that try to encompass modern needs, and ask how we can make sure that we build something that truly caters to editorial experience, and that can speak to developer experience as well.

I want to express my gratitude to Titus Wormer (@wooorm) for his insightful feedback on my first draft of this post, and for the great work he and the Unified.js team have done for the web community.