GraphQL is becoming popular and developers are constantly looking for frameworks that make it easy to set up a fast, secure and scalable GraphQL API. In this article, we will learn how to create a scalable and fast GraphQL API with authentication and fine-grained data-access control (authorization). As an example, we’ll build an API with register and login functionality. The API will be about users and confidential files so we’ll define advanced authorization rules that specify whether a logged-in user can access certain files.

By using FaunaDB’s native GraphQL and security layer, we receive all the necessary tools to set up such an API in minutes. FaunaDB has a free tier so you can easily follow along by creating an account at https://dashboard.fauna.com/. Since FaunaDB automatically provides the necessary indexes and translates each GraphQL query to one FaunaDB query, your API is also as fast as it can be (no n+1 problems!).

Setting up the API is simple: drop in a schema and we are ready to start. So let’s get started!

The use-case: users and confidential files

We need an example use-case that demonstrates how security and GraphQL API features can work together. In this example, there are users and files. Some files can be accessed by all users, and some are only meant to be accessed by managers. The following GraphQL schema will define our model:

type User {

username: String! @unique

role: UserRole!

}

enum UserRole {

MANAGER

EMPLOYEE

}

type File {

content: String!

confidential: Boolean!

}

input CreateUserInput {

username: String!

password: String!

role: UserRole!

}

input LoginUserInput {

username: String!

password: String!

}

type Query {

allFiles: [File!]!

}

type Mutation {

createUser(input: CreateUserInput): User! @resolver(name: "create_user")

loginUser(input: LoginUserInput): String! @resolver(name: "login_user")

}When looking at the schema, you might notice that the createUser and loginUser Mutation fields have been annotated with a special directive named @resolver. This is a directive provided by the FaunaDB GraphQL API, which allows us to define a custom behavior for a given Query or Mutation field. Since we’ll be using FaunaDB’s built-in authentication mechanisms, we will need to define this logic in FaunaDB after we import the schema.

Importing the schema

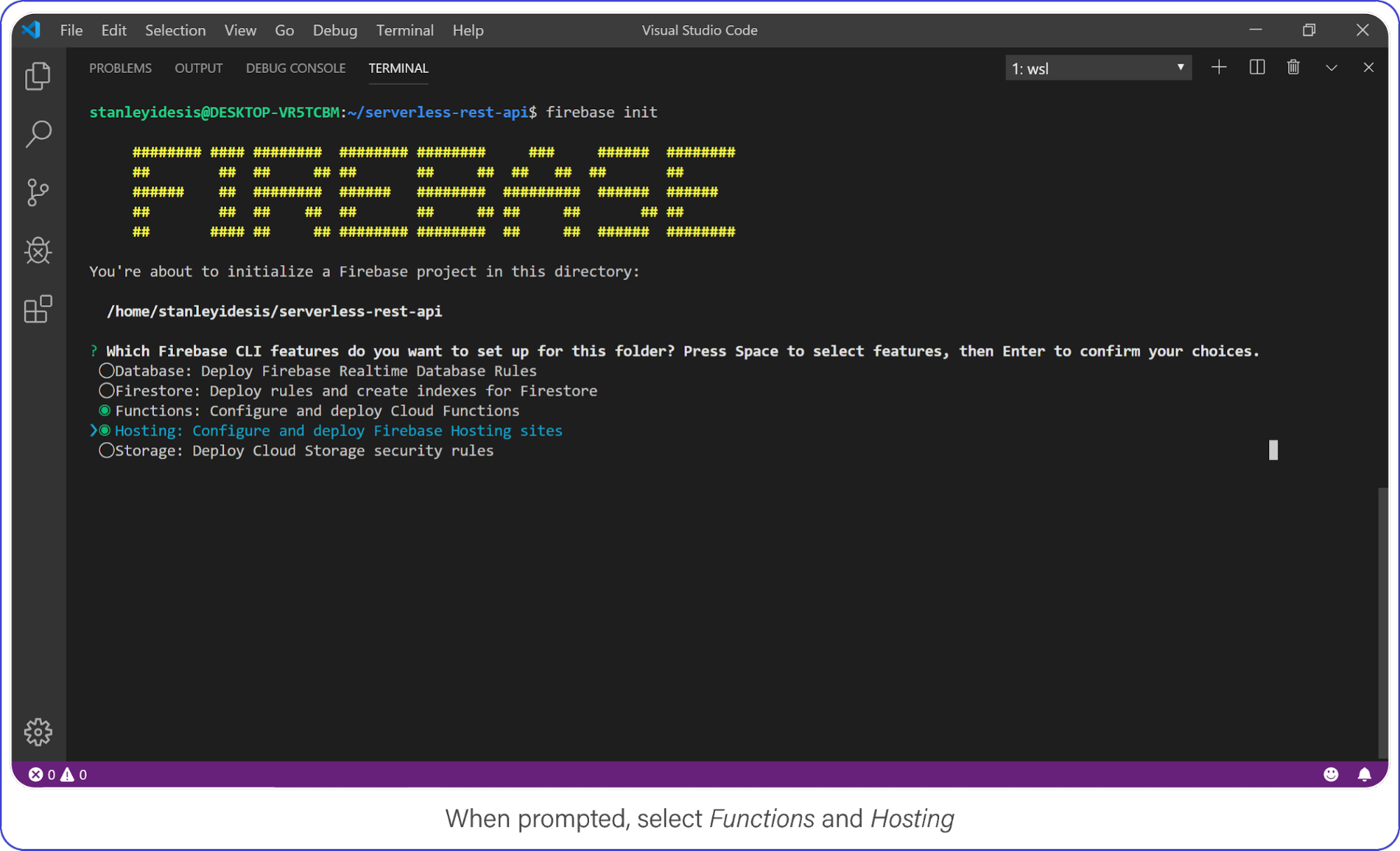

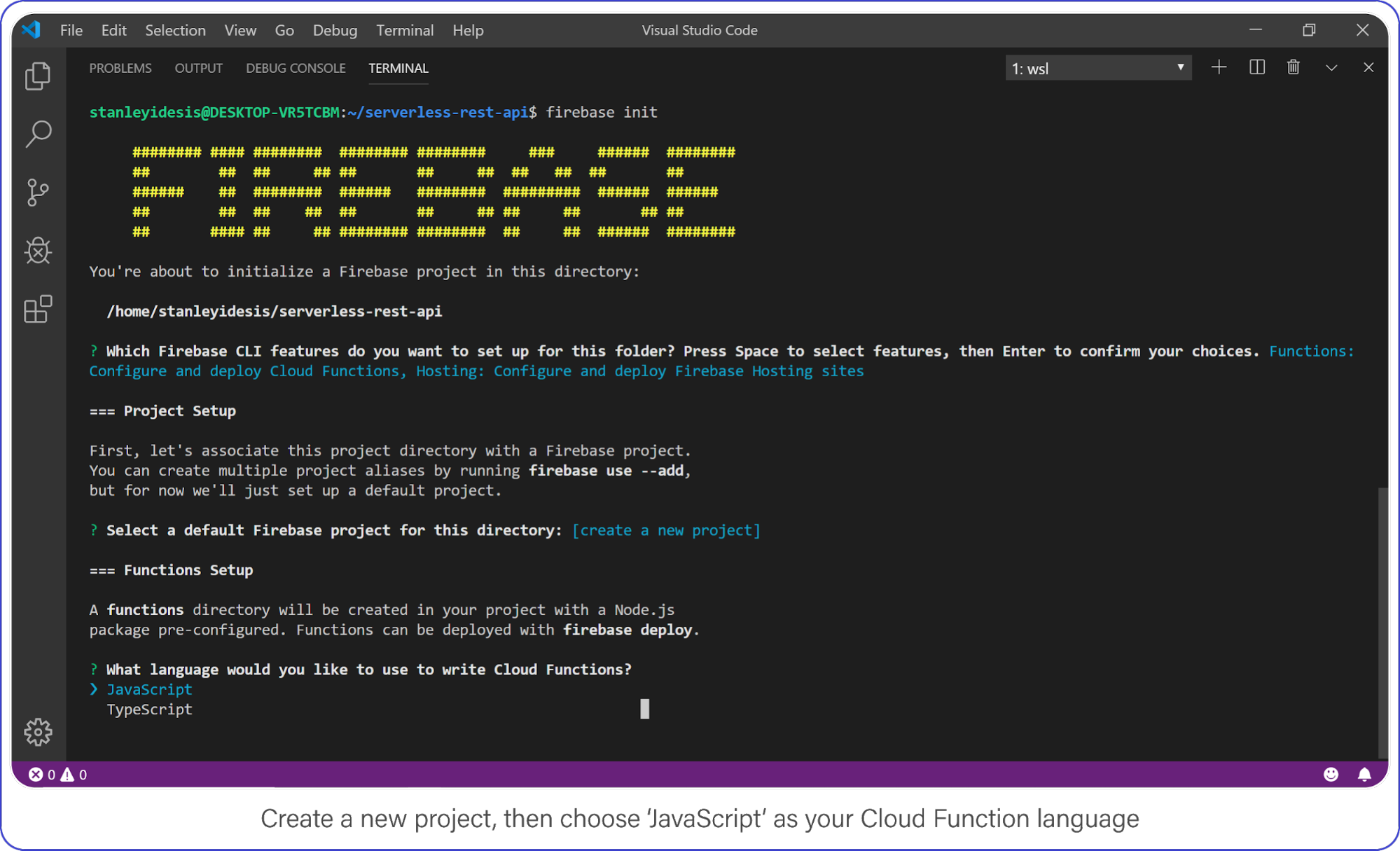

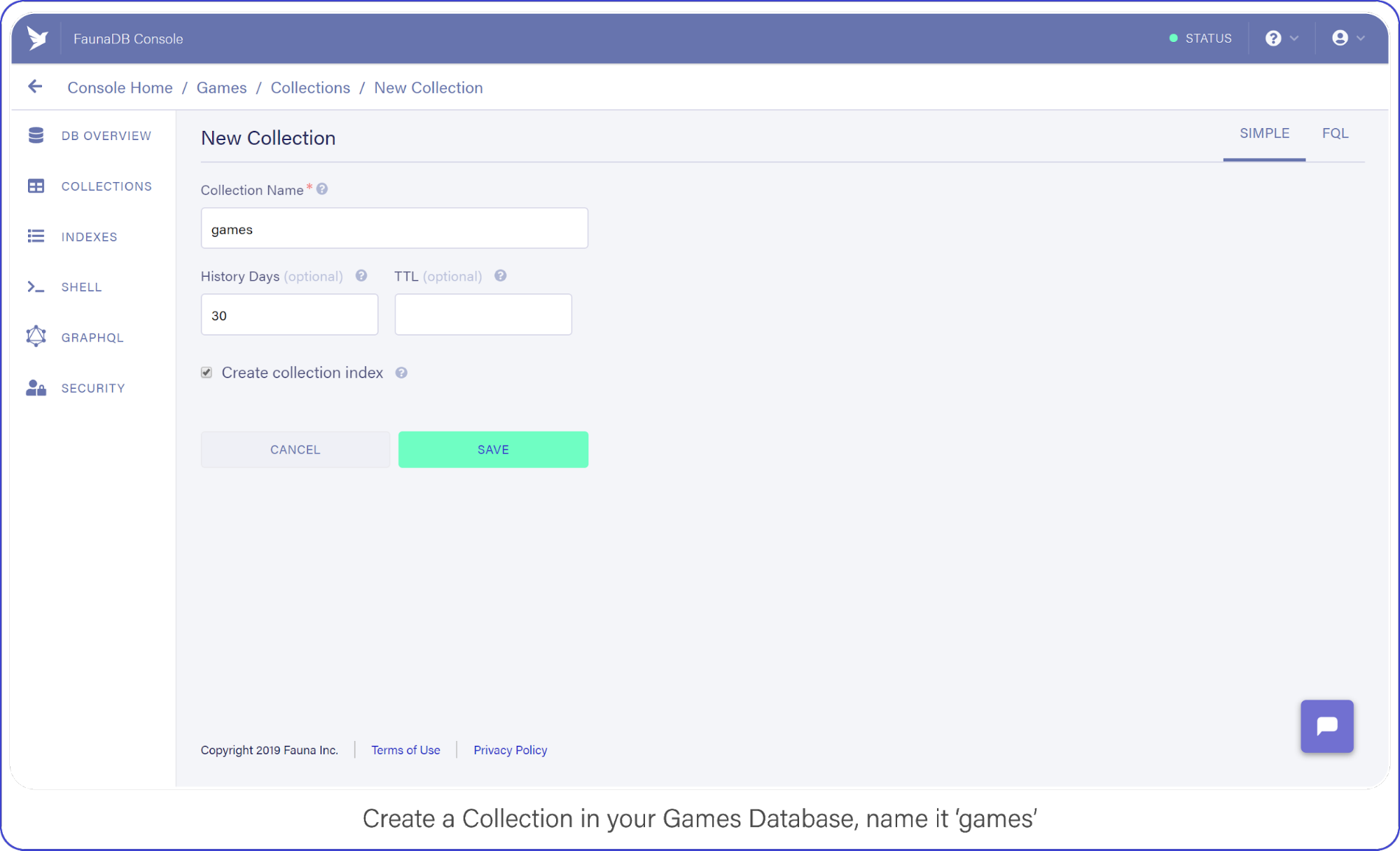

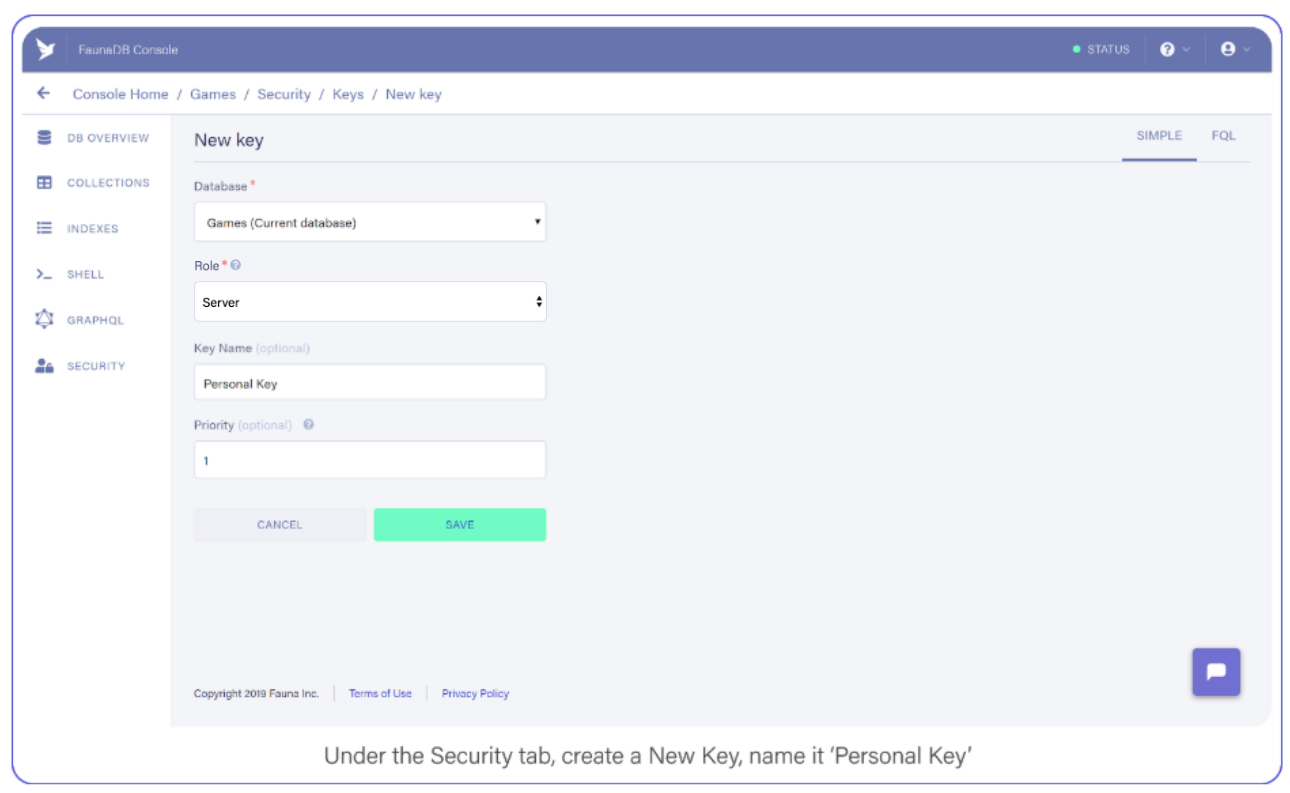

First, let’s import the example schema into a new database. Log into the FaunaDB Cloud Console with your credentials. If you don’t have an account yet, you can sign up for free in a few seconds.

Once logged in, click the "New Database" button from the home page:

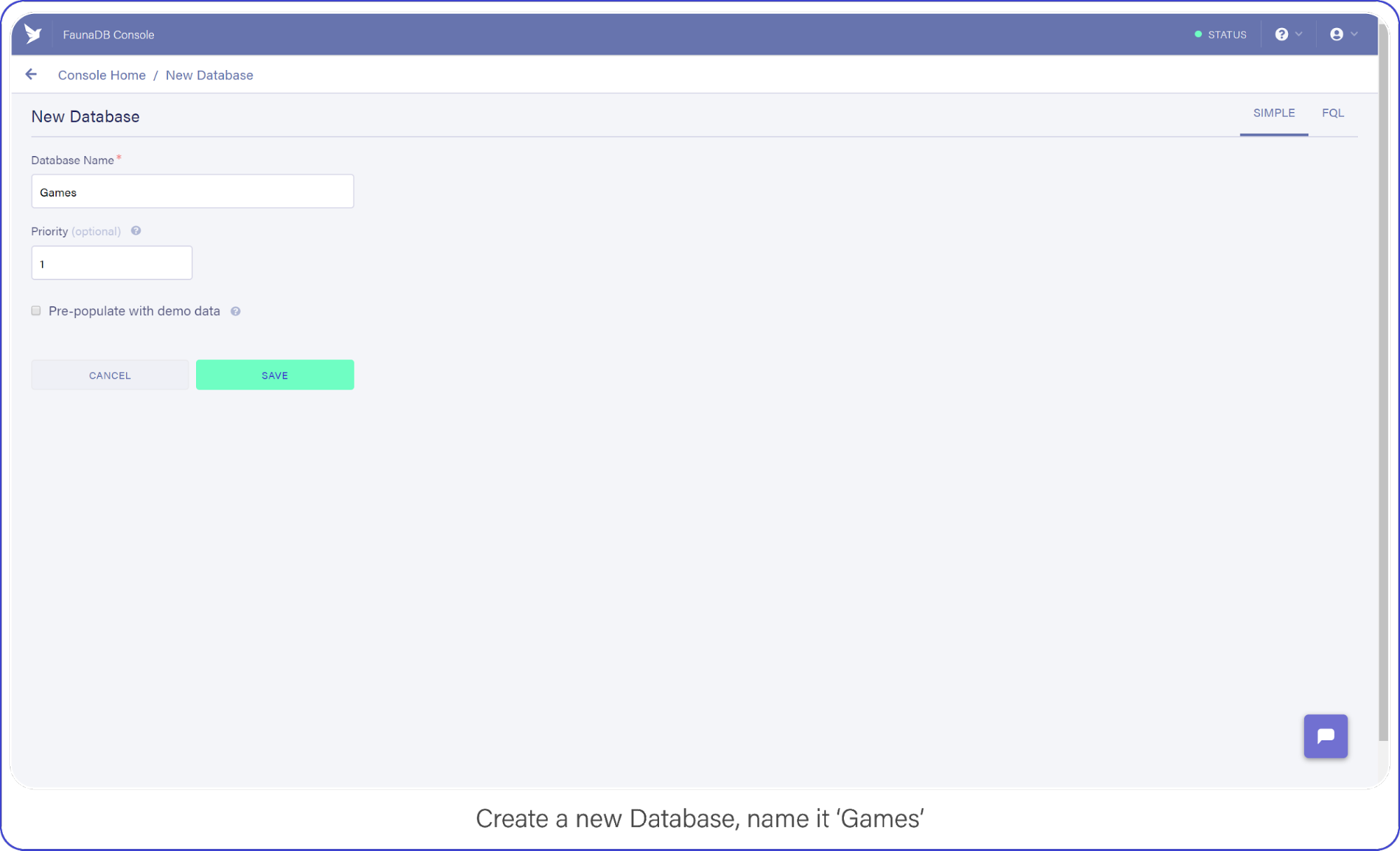

Choose a name for the new database, and click the "Save" button:

Next, we will import the GraphQL schema listed above into the database we just created. To do so, create a file named schema.gql containing the schema definition. Then, select the GRAPHQL tab from the left sidebar, click the "Import Schema" button, and select the newly-created file:

The import process creates all of the necessary database elements, including collections and indexes, for backing up all of the types defined in the schema. It automatically creates everything your GraphQL API needs to run efficiently.

You now have a fully functional GraphQL API which you can start testing out in the GraphQL playground. But we do not have data yet. More specifically, we would like to create some users to start testing our GraphQL API. However, since users will be part of our authentication, they are special: they have credentials and can be impersonated. Let’s see how we can create some users with secure credentials!

Custom resolvers for authentication

Remember the createUser and loginUser mutation fields that have been annotated with a special directive named @resolver. createUser is exactly what we need to start creating users, however the schema did not really define how a user needs to created; instead, it was tagged with a @resolver tag.

By tagging a specific mutation with a custom resolver such as @resolver(name: "create_user") we are informing FaunaDB that this mutation is not implemented yet but will be implemented by a User-defined function (UDF). Since our GraphQL schema does not know how to express this, the import process will only create a function template which we still have to fill in.

A UDF is a custom FaunaDB function, similar to a stored procedure, that enables users to define a tailor-made operation in Fauna’s Query Language (FQL). This function is then used as the resolver of the annotated field.

We will need a custom resolver since we will take advantage of the built-in authentication capabilities which can not be expressed in standard GraphQL. FaunaDB allows you to set a password on any database entity. This password can then be used to impersonate this database entity with the Login function which returns a token with certain permissions. The permissions that this token holds depend on the access rules that we will write.

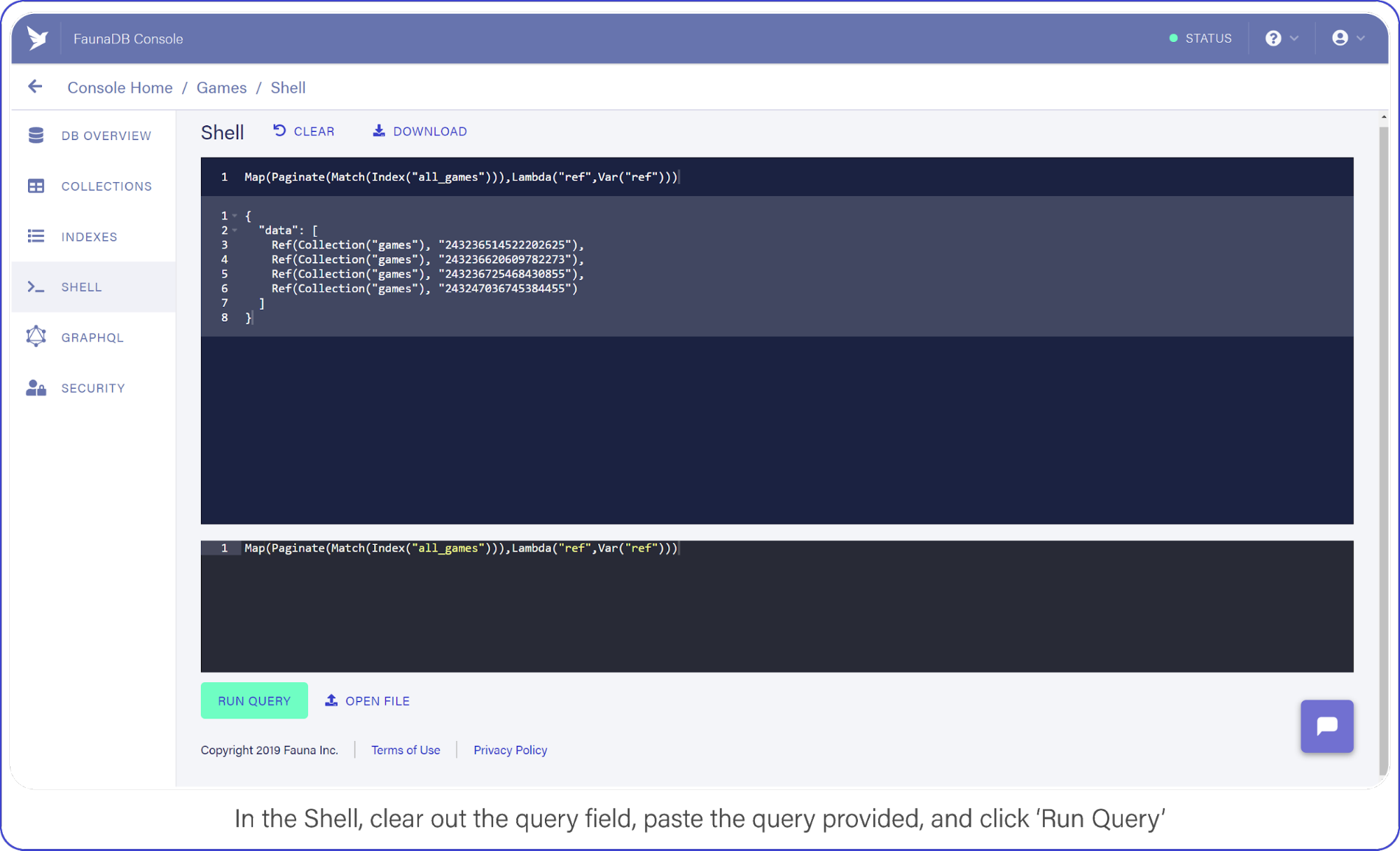

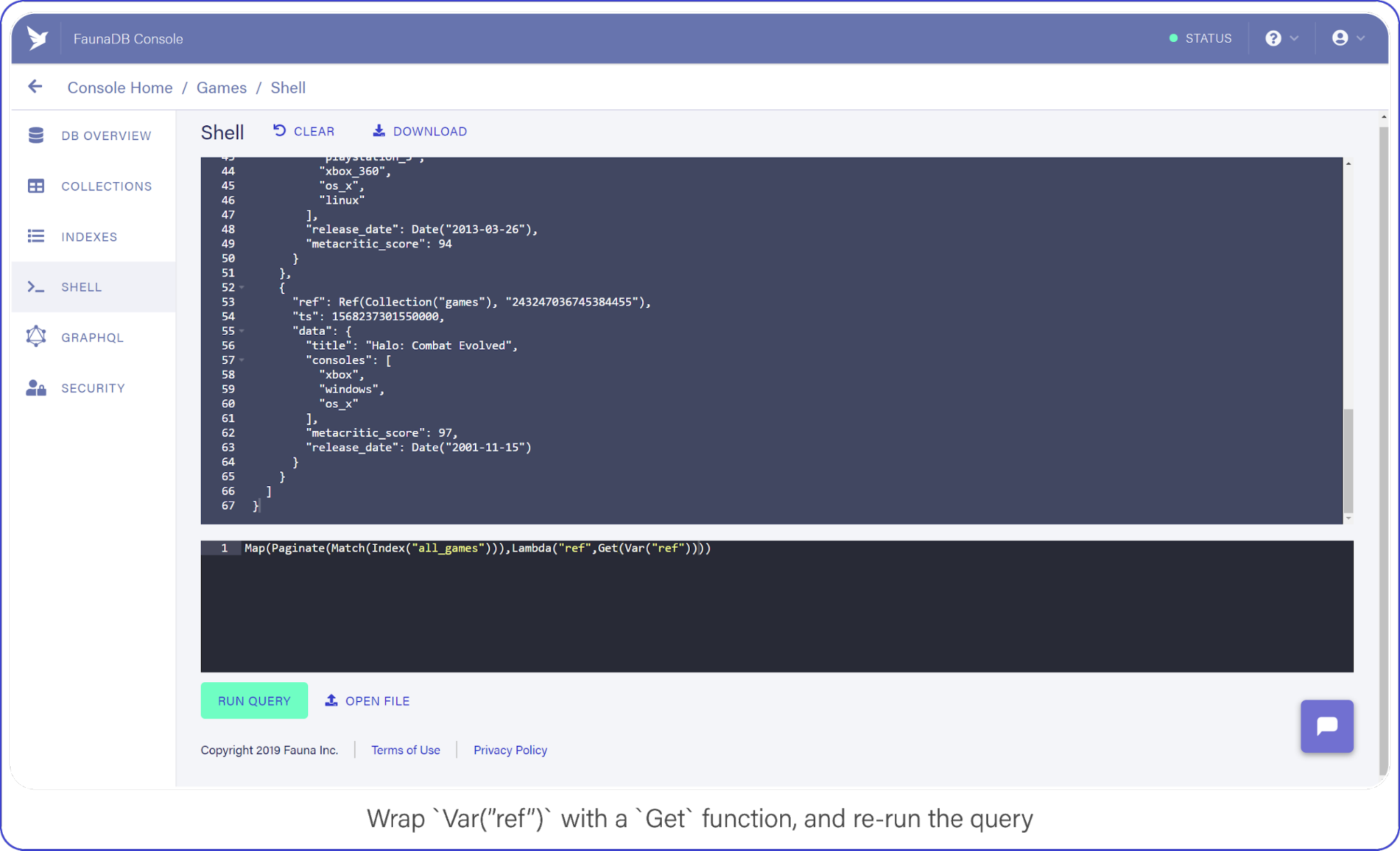

Let’s continue to implement the UDF for the createUser field resolver so that we can create some test users. First, select the Shell tab from the left sidebar:

As explained before, a template UDF has already been created during the import process. When called, this template UDF prints an error message stating that it needs to be updated with a proper implementation. In order to update it with the intended behavior, we are going to use FQL's Update function.

So, let’s copy the following FQL query into the web-based shell, and click the "Run Query" button:

Update(Function("create_user"), {

"body": Query(

Lambda(["input"],

Create(Collection("User"), {

data: {

username: Select("username", Var("input")),

role: Select("role", Var("input")),

},

credentials: {

password: Select("password", Var("input"))

}

})

)

)

});Your screen should look similar to:

The create_user UDF will be in charge of properly creating a User document along with a password value. The password is stored in the document within a special object named credentials that is encrypted and cannot be retrieved back by any FQL function. As a result, the password is securely saved in the database making it impossible to read from either the FQL or the GraphQL APIs. The password will be used later for authenticating a User through a dedicated FQL function named Login, as explained next.

Now, let’s add the proper implementation for the UDF backing up the loginUser field resolver through the following FQL query:

Update(Function("login_user"), {

"body": Query(

Lambda(["input"],

Select(

"secret",

Login(

Match(Index("unique_User_username"), Select("username", Var("input"))),

{ password: Select("password", Var("input")) }

)

)

)

)

});Copy the query listed above and paste it into the shell’s command panel, and click the "Run Query" button:

The login_user UDF will attempt to authenticate a User with the given username and password credentials. As mentioned before, it does so via the Login function. The Login function verifies that the given password matches the one stored along with the User document being authenticated. Note that the password stored in the database is not output at any point during the login process. Finally, in case the credentials are valid, the login_user UDF returns an authorization token called a secret which can be used in subsequent requests for validating the User’s identity.

With the resolvers in place, we will continue with creating some sample data. This will let us try out our use case and help us better understand how the access rules are defined later on.

Creating sample data

First, we are going to create a manager user. Select the GraphQL tab from the left sidebar, copy the following mutation into the GraphQL Playground, and click the "Play" button:

mutation CreateManagerUser {

createUser(input: {

username: "bill.lumbergh"

password: "123456"

role: MANAGER

}) {

username

role

}

}Your screen should look like this:

Next, let’s create an employee user by running the following mutation through the GraphQL Playground editor:

mutation CreateEmployeeUser {

createUser(input: {

username: "peter.gibbons"

password: "abcdef"

role: EMPLOYEE

}) {

username

role

}

}You should see the following response:

Now, let’s create a confidential file by running the following mutation:

mutation CreateConfidentialFile {

createFile(data: {

content: "This is a confidential file!"

confidential: true

}) {

content

confidential

}

}As a response, you should get the following:

And lastly, create a public file with the following mutation:

mutation CreatePublicFile {

createFile(data: {

content: "This is a public file!"

confidential: false

}) {

content

confidential

}

}If successful, it should prompt the following response:

Now that all the sample data is in place, we need access rules since this article is about securing a GraphQL API. The access rules determine how the sample data we just created can be accessed, since by default a user can only access his own user entity. In this case, we are going to implement the following access rules:

- Allow employee users to read public files only.

- Allow manager users to read both public files and, only during weekdays, confidential files.

As you might have already noticed, these access rules are highly specific. We will see however that the ABAC system is powerful enough to express very complex rules without getting in the way of the design of your GraphQL API.

Such access rules are not part of the GraphQL specification so we will define the access rules in the Fauna Query Language (FQL), and then verify that they are working as expected by executing some queries from the GraphQL API.

But what is this "ABAC" system that we just mentioned? What does it stand for, and what can it do?

What is ABAC?

ABAC stands for Attribute-Based Access Control. As its name indicates, it’s an authorization model that establishes access policies based on attributes. In simple words, it means that you can write security rules that involve any of the attributes of your data. If our data contains users we could use the role, department, and clearance level to grant or refuse access to specific data. Or we could use the current time, day of the week, or location of the user to decide whether he can access a specific resource.

In essence, ABAC allows the definition of fine-grained access control policies based on environmental properties and your data. Now that we know what it can do, let’s define some access rules to give you concrete examples.

Defining the access rules

In FaunaDB, access rules are defined in the form of roles. A role consists of the following data:

- name — the name that identifies the role

- privileges — specific actions that can be executed on specific resources

- membership — specific identities that should have the specified privileges

Roles are created through the CreateRole FQL function, as shown in the following example snippet:

CreateRole({

name: "role_name",

membership: [ // ... ],

privileges: [ // ... ]

})You can see two important concepts in this role; membership and privileges. Membership defines who receives the privileges of the role and privileges defines what these permissions are. Let’s write a simple example rule to start with: “Any user can read all files.”

Since the rule applies on all users, we would define the membership like this:

membership: {

resource: Collection("User")

}Simple right? We then continue to define the "Can read all files" privilege for all of these users.

privileges: [

{

resource: Collection("File"),

actions: { read: true }

}

]The direct effect of this is that any token that you receive by logging in with a user via our loginUser GraphQL mutation can now access all files.

This is the simplest rule that we can write, but in our example we want to limit access to some confidential files. To do that, we can replace the {read: true} syntax with a function. Since we have defined that the resource of the privilege is the "File" collection, this function will take each file that would be accessed by a query as the first parameter. You can then write rules such as: “A user can only access a file if it is not confidential”. In FaunaDB’s FQL, such a function is written by using Query(Lambda(‘x’, … <logic that users Var(‘x’)>)).

Below is the privilege that would only provide read access to non-confidential files:

privileges: [

{

resource: Collection("File"),

actions: {

// Read and establish rule based on action attribute

read: Query(

// Read and establish rule based on resource attribute

Lambda("fileRef",

Not(Select(["data", "confidential"], Get(Var("fileRef"))))

)

)

}

}

]This directly uses properties of the "File" resource we are trying to access. Since it’s just a function, we could also take into account environmental properties like the current time. For example, let’s write a rule that only allows access on weekdays.

privileges: [

{

resource: Collection("File"),

actions: {

read: Query(

Lambda("fileRef",

Let(

{

dayOfWeek: DayOfWeek(Now())

},

And(GTE(Var("dayOfWeek"), 1), LTE(Var("dayOfWeek"), 5))

)

)

)

}

}

]As mentioned in our rules, confidential files should only be accessible by managers. Managers are also users, so we need a rule that applies to a specific segment of our collection of users. Luckily, we can also define the membership as a function; for example, the following Lambda only considers users who have the MANAGER role to be part of the role membership.

membership: {

resource: Collection("User"),

predicate: Query( // Read and establish rule based on user attribute

Lambda("userRef",

Equals(Select(["data", "role"], Get(Var("userRef"))), "MANAGER")

)

)

}In sum, FaunaDB roles are very flexible entities that allow defining access rules based on all of the system elements' attributes, with different levels of granularity. The place where the rules are defined — privileges or membership — determines their granularity and the attributes that are available, and will differ with each particular use case.

Now that we have covered the basics of how roles work, let’s continue by creating the access rules for our example use case!

In order to keep things neat and tidy, we’re going to create two roles: one for each of the access rules. This will allow us to extend the roles with further rules in an organized way if required later. Nonetheless, be aware that all of the rules could also have been defined together within just one role if needed.

Let’s implement the first rule:

“Allow employee users to read public files only.”

In order to create a role meeting these conditions, we are going to use the following query:

CreateRole({

name: "employee_role",

membership: {

resource: Collection("User"),

predicate: Query(

Lambda("userRef",

// User attribute based rule:

// It grants access only if the User has EMPLOYEE role.

// If so, further rules specified in the privileges

// section are applied next.

Equals(Select(["data", "role"], Get(Var("userRef"))), "EMPLOYEE")

)

)

},

privileges: [

{

// Note: 'allFiles' Index is used to retrieve the

// documents from the File collection. Therefore,

// read access to the Index is required here as well.

resource: Index("allFiles"),

actions: { read: true }

},

{

resource: Collection("File"),

actions: {

// Action attribute based rule:

// It grants read access to the File collection.

read: Query(

Lambda("fileRef",

Let(

{

file: Get(Var("fileRef")),

},

// Resource attribute based rule:

// It grants access to public files only.

Not(Select(["data", "confidential"], Var("file")))

)

)

)

}

}

]

})Select the Shell tab from the left sidebar, copy the above query into the command panel, and click the "Run Query" button:

Next, let’s implement the second access rule:

“Allow manager users to read both public files and, only during weekdays, confidential files.”

In this case, we are going to use the following query:

CreateRole({

name: "manager_role",

membership: {

resource: Collection("User"),

predicate: Query(

Lambda("userRef",

// User attribute based rule:

// It grants access only if the User has MANAGER role.

// If so, further rules specified in the privileges

// section are applied next.

Equals(Select(["data", "role"], Get(Var("userRef"))), "MANAGER")

)

)

},

privileges: [

{

// Note: 'allFiles' Index is used to retrieve

// documents from the File collection. Therefore,

// read access to the Index is required here as well.

resource: Index("allFiles"),

actions: { read: true }

},

{

resource: Collection("File"),

actions: {

// Action attribute based rule:

// It grants read access to the File collection.

read: Query(

Lambda("fileRef",

Let(

{

file: Get(Var("fileRef")),

dayOfWeek: DayOfWeek(Now())

},

Or(

// Resource attribute based rule:

// It grants access to public files.

Not(Select(["data", "confidential"], Var("file"))),

// Resource and environmental attribute based rule:

// It grants access to confidential files only on weekdays.

And(

Select(["data", "confidential"], Var("file")),

And(GTE(Var("dayOfWeek"), 1), LTE(Var("dayOfWeek"), 5))

)

)

)

)

)

}

}

]

})Copy the query into the command panel, and click the "Run Query" button:

At this point, we have created all of the necessary elements for implementing and trying out our example use case! Let’s continue with verifying that the access rules we just created are working as expected...

Putting everything in action

Let’s start by checking the first rule:

“Allow employee users to read public files only.”

The first thing we need to do is log in as an employee user so that we can verify which files can be read on its behalf. In order to do so, execute the following mutation from the GraphQL Playground console:

mutation LoginEmployeeUser {

loginUser(input: {

username: "peter.gibbons"

password: "abcdef"

})

}As a response, you should get a secret access token. The secret represents that the user has been authenticated successfully:

At this point, it’s important to remember that the access rules we defined earlier are not directly associated with the secret that is generated as a result of the login process. Unlike other authorization models, the secret token itself does not contain any authorization information on its own, but it’s just an authentication representation of a given document.

As explained before, access rules are stored in roles, and roles are associated with documents through their membership configuration. After authentication, the secret token can be used in subsequent requests to prove the caller’s identity and determine which roles are associated with it. This means that access rules are effectively verified in every subsequent request and not only during authentication. This model enables us to modify access rules dynamically without requiring users to authenticate again.

Now, we will use the secret issued in the previous step to validate the identity of the caller in our next query. In order to do so, we need to include the secret as a Bearer Token as part of the request. To achieve this, we have to modify the Authorization header value set by the GraphQL Playground. Since we don’t want to miss the admin secret that is being used as default, we’re going to do this in a new tab.

Click the plus (+) button to create a new tab, and select the HTTP HEADERS panel on the bottom left corner of the GraphQL Playground editor. Then, modify the value of the Authorization header to include the secret obtained earlier, as shown in the following example. Make sure to change the scheme value from Basic to Bearer as well:

{

"authorization": "Bearer fnEDdByZ5JACFANyg5uLcAISAtUY6TKlIIb2JnZhkjU-SWEaino"

}With the secret properly set in the request, let’s try to read all of the files on behalf of the employee user. Run the following query from the GraphQL Playground:

query ReadFiles {

allFiles {

data {

content

confidential

}

}

}In the response, you should see the public file only:

Since the role we defined for employee users does not allow them to read confidential files, they have been correctly filtered out from the response!

Let’s move on now to verifying our second rule:

“Allow manager users to read both public files and, only during weekdays, confidential files.”

This time, we are going to log in as the employee user. Since the login mutation requires an admin secret token, we have to go back first to the original tab containing the default authorization configuration. Once there, run the following query:

mutation LoginManagerUser {

loginUser(input: {

username: "bill.lumbergh"

password: "123456"

})

}You should get a new secret as a response:

Copy the secret, create a new tab, and modify the Authorization header to include the secret as a Bearer Token as we did before. Then, run the following query in order to read all of the files on behalf of the manager user:

query ReadFiles {

allFiles {

data {

content

confidential

}

}

}As long as you’re running this query on a weekday (if not, feel free to update this rule to include weekends), you should be getting both the public and the confidential file in the response:

And, finally, we have verified that all of the access rules are working successfully from the GraphQL API!

Conclusion

In this post, we have learned how a comprehensive authorization model can be implemented on top of the FaunaDB GraphQL API using FaunaDB's built-in ABAC features. We have also reviewed ABAC's distinctive capabilities, which allow defining complex access rules based on the attributes of each system component.

While access rules can only be defined through the FQL API at the moment, they are effectively verified for every request executed against the FaunaDB GraphQL API. Providing support for specifying access rules as part of the GraphQL schema definition is already planned for the future.

In short, FaunaDB provides a powerful mechanism for defining complex access rules on top of the GraphQL API covering most common use cases without the need for third-party services.

The post Instant GraphQL Backend with Fine-grained Security Using FaunaDB appeared first on CSS-Tricks.