What's happening when you see some JavaScript that calls super()?.In a child class, you use super() to call its parent’s constructor and super.<methodName> to access its parent’s methods. This article will assume at least a little familiarity with the concepts of constructors and child and parent classes. If that's totally new, you may want to start with Mozilla's article on Object-oriented JavaScript for beginners.

Super isn't unique to Javascript — many programming languages, including Java and Python, have a super() keyword that provides a reference to a parent class. JavaScript, unlike Java and Python, is not built around a class inheritance model. Instead, it extends JavaScript’s prototypal inheritance model to provide behavior that’s consistent with class inheritance.

Let’s learn a bit more about it and look at some code samples.

First off, here’s a quote from Mozilla’s web docs for classes:

JavaScript classes, introduced in ECMAScript 2015, are primarily syntactical sugar over JavaScript's existing prototype-based inheritance. The class syntax does not introduce a new object-oriented inheritance model to JavaScript.

An example of a simple child and parent class will help illustrate what this quote really means:

See the Pen

ZEzggLK by Bailey Jones (@bailey_jones)

on CodePen.

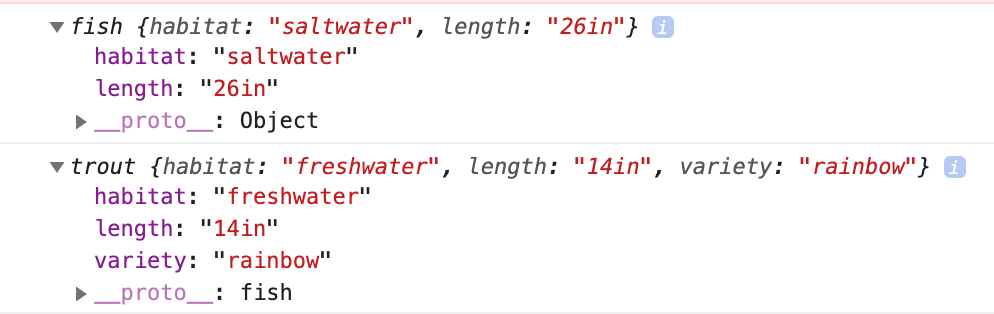

My example has two classes: fish and trout. All fish have information for habitat and length, so those properties belong to the fish class. Trout also has a property for variety, so it extends fish to build on top of the other two properties. Here are the constructors for fish and trout:

class fish {

constructor(habitat, length) {

this.habitat = habitat

this.length = length

}

}

class trout extends fish {

constructor(habitat, length, variety) {

super(habitat, length)

this.variety = variety

}

}The fish class’s constructor defines habitat and length, and the trout’s constructor defines variety. I have to call super() in trout’s constructor, or I’ll get a reference error when I try to set this.variety. That's because on line one of the trout class, I told JavaScript that trout is a child of fish using the extends keyword. That means trout’s this context includes the properties and methods defined in the fish class, plus whatever properties and methods trout defines for itself. Calling super() essentially lets JavaScript know what a fish is so that it can create a this context for trout that includes everything from fish, plus everything we’re about to define for trout. The fish class doesn’t need super() because its “parent” is just the JavaScript Object. Fish is already at the top of the prototypal inheritance chain, so calling super() is not necessary — fish’s this context only needs to include Object, which JavaScript already knows about.

Object → fish → trout.I called super(habitat, length) in trout’s constructor (referencing the fish class), making all three properties immediately available on the this context for trout. There’s actually another way to get the same behavior out of trout’s constructor. I must call super() to avoid a reference error, but I don’t have to call it “correctly” with parameters that fish's constructor expects. That's because I don't have to use super() to assign values to the fields that fish creates — I just have to make sure that those fields exist on trout's this context. This is an important difference between JavaScript and a true class inheritance model, like Java, where the following code could be illegal depending on how I implemented the fish class:

class trout extends fish {

constructor(habitat, length, variety) {

super()

this.habitat = habitat

this.length = length

this.variety = variety

}

}This alternate trout constructor makes it harder to tell which properties belong to fish and which belong to trout, but it gets the same result as the previous example. The only difference is that here, calling super() with no parameters creates the properties habitat and length on the current this context without assigning anything to them. If I called console.log(this) after line three, it would print {habitat: undefined, length: undefined}. Lines four and five assign values.

I can also use super() outside of trout’s constructor in order to reference methods on the parent class. Here I’ve defined a renderProperties method that will display all the class’s properties into the HTML element I pass to it. super() is useful here because I want my trout class to implement a similar method that does the same thing plus a little more — it assigns a class name to the element before updating its HTML. I can reuse the logic from the fish class by calling super.renderProperties() inside the relevant class function.

class fish {

renderProperties(element) {

element.innerHTML = JSON.stringify(this)

}

}

class trout extends fish {

renderPropertiesWithSuper(element) {

element.className="green"

super.renderProperties(element);

}The name you choose is important. I’ve called my method in the trout class renderPropertiesWithSuper() because I still want to have the option of calling trout.renderProperties() as it’s defined on the fish class. If I’d just named the function in the trout class renderProperties, that would be perfectly valid; however, I’d no longer be able to access both functions directly from an instance of trout - calling trout.renderProperties would call the function defined on trout. This isn't necessarily a useful implementation - it's an arguably better pattern for a function that calls super like this to overwrite its parent function's name - but it does illustrate how flexible JavaScript allows your classes to be.

It is completely possible to implement this example without the use of the super() or extends keywords that were so helpful in the previous code sample, it's just much less convenient. That's what Mozilla meant by "syntactical sugar." In fact, if I plugged my previous code into a transpiler like Babel to make sure my classes worked with older versions of JavaScript, it would generate something closer to the following code. The code here is mostly the same, but you'll notice that without extends and super(), I have to define fish and trout as functions and access their prototypes directly. I also have to do some extra wiring on lines 15, 16, and 17 to establish trout as a child of fish and to make sure trout can be passed the correct this context in its constructor. If you're interested in a deep dive into what's going on here, Eric Green has an excellent post with lots of code samples on how to build classes with and without ES2015.

See the Pen

wvvdxdd by Bailey Jones (@bailey_jones)

on CodePen.

Classes in JavaScript are a powerful way to share functionality. Class components in React, for example, rely on them. However, if you're used to Object Oriented programming in another language that uses a class inheritance model, JavaScript's behavior can occasionally be surprising. Learning the basics of prototypal inheritance can help clarify how to work with classes in JavaScript.

The post What is super() in JavaScript? appeared first on CSS-Tricks.